Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

Methodological

analyses for determining thermal requirements of grape varieties in Tandil,

Argentina

Análisis de metodologías

para determinar los requerimientos térmicos de variedades de vid en Tandil,

Argentina

Laura Aguas1,

Gabriela Hernandez1,

Juan Laddaga1

1 Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires

(UNCPBA). Facultad de Agronomía. NAACCE (Núcleo de estudios en actividades

agropecuarias y cambio climático). República de Italia 780. Azul (7300). Buenos

Aires. Argentina.

* lrodriguez@azul.faa.unicen.edu.ar

Abstract

This study

evaluated the thermal demand of different grapevine varieties (Cabernet Franc,

Merlot, Semillón, and Tannat) in Don Bosco, Tandil, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Phenology was evaluated during four productive cycles, identifying periods from

budburst to flowering onset (BB-FO), flowering onset to veraison onset (FO-VO),

and veraison onset to maturity (VO-M). The National Meteorological Service of

Argentina provided daily maximum and minimum air temperatures. Six thermal sum

methods were used: methods 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 depended on base temperature for

vine development (10°C); methods 2.1 and 2.2, considered base temperature and

optimum temperature (25°C); and method 3, considered base, optimum, and

threshold temperature (35°C). These methods were evaluated using the standard

error of the thermal sum. Methods 2.2 and 3 best fit all four varieties,

allowing adequate estimates of cumulative daily heat summation.

Keywords: degree-days, Vitis

vinifera L.,

phenology, temperate-humid climate

Resumen

El presente estudio

tuvo como objetivo evaluar los requerimientos térmicos de diferentes variedades

de vid (Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Semillón y Tannat) en viñedos plantados en Don

Bosco, Tandil, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Se evaluó cronológicamente el

desarrollo fenológico durante cuatro ciclos productivos, identificando las

fechas de ocurrencia de los eventos y delimitando la duración de los

subperíodos en días: inicio de brotación a inicio de floración, inicio de

floración a inicio de envero, y envero a madurez. Las temperaturas máximas y

mínimas diarias del aire se obtuvieron de los registros del Servicio

Meteorológico Nacional. Se emplearon seis métodos de suma térmica: los métodos

1.1, 1.2 y 1.3, que se basan exclusivamente en la temperatura base para el

desarrollo de la vid (10°C); los métodos 2.1 y 2.2, que, además de la

temperatura base, consideran también la temperatura óptima (25°C); y el método

3, que incorpora los parámetros anteriores junto con la temperatura umbral

(35°C). Estos métodos se evaluaron utilizando el error estándar de la suma

térmica. Los métodos 2.2 y 3 demostraron el mejor ajuste para las cuatro

variedades. Concluimos que los métodos 2.2 y 3 son más precisos en la estimación

de la suma térmica diaria para todas las variedades estudiadas.

Palabras clave: grados-días, Vitis

vinifera L.,

fenología, clima templado-húmedo

Originales: Recepción: 18/10/2023 - Aceptación: 06/02/2025

Introduction

Among climatic

factors, temperature plays a fundamental role in crop development. Temperature

controls vegetative growth and development. Thermal weather models predicting

plant development confirm its crucial role in phenology (54).

Grapevine (Vitis

vinifera L.) is one widely cultivated fruit crop (30). Optimal

production largely depends on local climatic conditions in each growing region (5). In modern

viticulture, identifying phenological phases for each cultivar is crucial for

effective crop management (21, 41). In recent

decades, several investigations have focused on predicting grapevine budburst,

flowering, and ripening (2, 15). Phenological

characterization and quantification of thermal units for each phase allow

harvest date estimations, suggesting site potential for viticulture (36). Thermal

quantification, known as thermal sum (39) and typically

expressed as degree-days (C° d) is widely used to account for temperature

effects on plant development (40, 43). Daily thermal sum

(DTS) considers average ambient temperature and basal temperature (BT) for each

species. Grapevine has a DTS of 10°C. When the value after subtracting BT from

average temperature is positive, degree-days are accumulated (16,

17, 25). This accumulated C°d can be calculated on a daily or monthly

basis, for each phenological stage (20). Villaseca

et al. (1986) indicated 850 to 950 C°d for early maturing table grape

varieties and 1150 to 1350 C° d for late maturing cultivars in Chile.

Chronological times between phenological stages vary with variety, climate, and

geographic location (48). Thus, before

introducing grape varieties in new regions, environmental effects on phenology

should be considered for better technological management (4).

Unfortunately,

research on grape phenology in southeastern Buenos Aires, Argentina, is

limited, especially when compared to other regions of the country, such as

Mendoza (14). In this province, the hilly area of Tandil constitutes

a promising region for viticulture. According to Godoy and Gancedo (2022) hilly areas

adequately satisfy the thermal needs of Merlot and Cabernet Franc, being Tandil

an emerging region. European grape varieties of different cycles and origins

are being evaluated in Tandil. According to the National Institute of Viticulture

of Argentina (2022), vineyards in Buenos Aires grew by 200% between 2011 and 2021.

Several authors consider a BT of 10 °C to characterize varietal

thermal requirements (29, 32, 35, 39). However, this

varies with phenology. The optimal growth temperature ranges from 25 to 30°C (9). Above 30°C,

growth decelerates, ceasing at approximately 38°C (38). Research on

optimal temperature for each developmental stage indicates optimal average

daily temperature for budburst above 10-12°C, between 18 and 22°C for

flowering, between 22 and 26°C from flowering to veraison, and between 20 and

24°C from veraison to ripening (38).

Methods to

calculate DTS are related to cardinal temperatures for plant development or

based on air temperature (53). The former are

grouped according to whether they only rely on BT or include optimum or upper

threshold temperatures for plant development. The latter are grouped according

to whether they rely on mean air temperature or also consider minimum and

maximum temperatures (40, 51).

Defining

phenological stages allows for rationalizing and optimizing cultural practices

in vine cultivation (26). This study

evaluated thermal requirements of Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Semillón, and Tannat

varieties, by different calculation methods in the hilly region of Tandil,

Buenos Aires province.

Materials

and methods

The research was

conducted at a commercial property called “Viñedo y Bodegas Cordón Blanco,” in

Tandil, southeastern Buenos Aires province (37°22’28” S, 59°06’23” W, altitude

of 271 m) (figure

1).

Figure 1. Aerial

view of the “Cordón Blanco” vineyard, located in Tandil, Buenos Aires province,

Argentina, in September 2021.

Figura

1. Vista aérea del viñedo “Cordón Blanco”, ubicado en

Tandil, Buenos Aires, en septiembre del 2021.

The 1.8-hectare

vineyard was planted in 2008 with 1.8 m between rows, 1.2 m between plants, and

4,700 plants per hectare. It is subdivided into 40 x 25 m plots, with one vine

variety per plot. We assessed four plots with Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Semillón,

and Tannat. Soil is clayey and climate is temperate-humid with mild summers.

Average annual temperature is 14.2°C, and average annual rainfall is 827 mm.

Considering vine growing cycle from September to March, average rainfall is

539.5 mm, and average maximum and minimum temperatures are 23.9°C and 9.8°C,

respectively (data provided by the National Meteorological Service of

Argentina, SMN).

The vineyard was agronomically managed by pruning and

phytosanitary controls. The four varieties were grafted onto a ‘101-14 Mgt’

rootstock, a V. riparia/V. rupestris hybrid, easy to root and graft, and

resistant to Daktulosphaira vitifoliae (phylloxera) (31). Starting in 2013,

monitoring began from budburst to berry softening during 2013 - 2014, 2016 -

2017, 2018 - 2019, and 2019 - 2020 seasons. Determinations started from the

fifth growth cycle, with a fully established crop, selecting five plants from

different points within each plot, considered replicates. Phenology related to

thermal summation was evaluated chronologically by identifying dates for each

event, determining subperiods, in days.

Main phenological

stages (24) were identified via Biologische

Bundesanstalt Bundessortenamt Chemise (BBCH) scale, including sub-stages 05

(10-15% budburst) to 09 (end of budburst), 65 (flowering), 81 (veraison onset),

and 85 (softening of berries, start of grape maturation). Budburst was

determined when 50% of buds had visibly burst, at sub-stage 07 in the BBCH

scale. Sub-stage 81 (veraison onset) was established by berry color change.

Following this phenological scale, varietal growth cycles were evaluated up to

sub-stage 85, until berry softening.

Minimum (Tmin) and maximum (Tmax) air temperatures and daily

rainfall were obtained from the SMN. Daily mean air temperature (Tm) was

calculated as the arithmetic mean between daily Tmin and Tmax. As described,

thermal requirements were calculated as the sum of degree-days (°C d) for each

phenological sub-period and from budburst to ripening. DTS (C° d) was

determined via six different methods: method 1.1 (12), method 1.2 (52), method 1.3 (45,

47), method 2.1 (34), method 2.3 (28), and method 3 (49,

55). These were grouped according to whether they used only BT

(methods 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3), i.e. the temperature at which the vine

metabolic process is minimum (10°C), the optimum temperature (OT) (methods 2.1

and 2.2), or the three cardinal temperatures: BT, OT and upper threshold (TT)

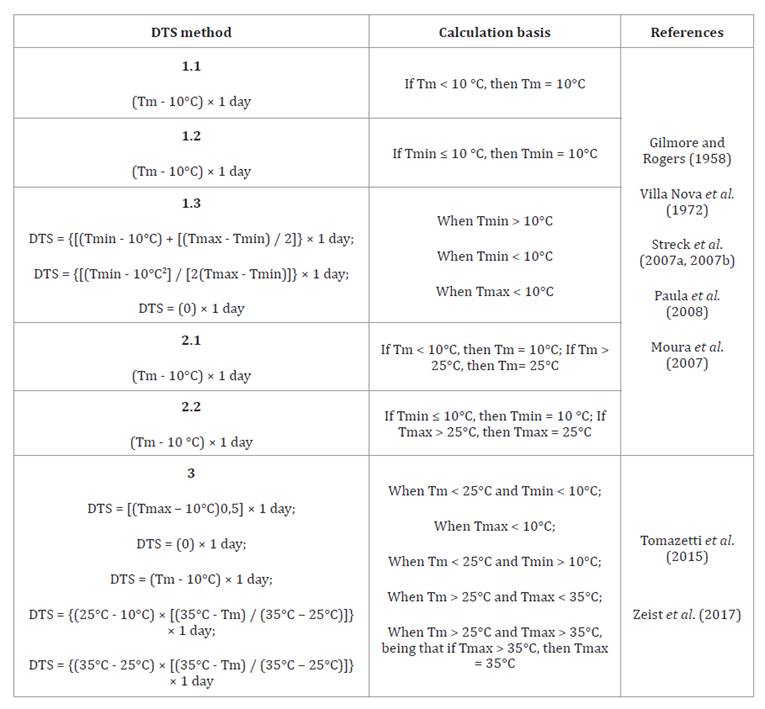

(method 3). Table

1

shows all six methods.

Table 1. Daily

thermal sum (DTS) methods used, equation, calculation concerning temperature

parameters, and references.

Tabla

1. Método de suma térmica diaria (STD)

utilizado con la fórmula final, su base de cálculo en relación con las

temperaturas empleadas y la bibliografía asociada a cada método.

Tmax is maximum temperature, Tm

is mean temperature, and Tmin is minimum temperature. Cardinal temperatures are

the lower basal temperature (10°C), the optimum temperature (25°C), and the

upper threshold temperature (35°C).

Tmax se refiere a la temperatura

máxima, Tm a la temperatura media y Tmin a la temperatura mínima. Las

temperaturas cardinales son: Temperatura base inferior (10°C), óptima (25°C) y

umbral superior (35°C).

For BT, OT, and TT,

10, 25, and 35°C were adopted respectively (55) (table 1). Cumulative

thermal sum (CTS) for the whole cycle and each subperiod included individual

DTS, i.e. CTS = ΣDTS (12, 44). Years were

considered replicates and varietal CTS was assessed by calculating the standard

error of the mean (SE). The SE of the CTS was obtained after calculating the

standard deviation of the mean CTS for each year. The thermal requirements

needed to complete the cycle and each phenological stage were subjected to

ANOVA and compared by Tukey’s test, with Infostat software (10) at p ≥ 0.05.

Results

and discussion

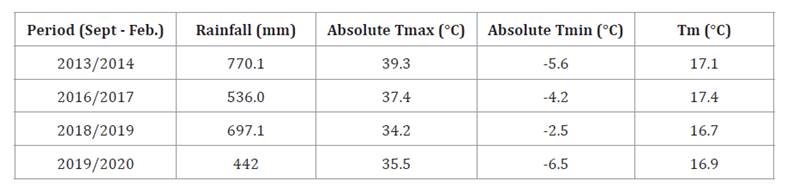

During the four years, absolute minimum and maximum temperatures

fluctuated between -6.5°C and 39.3°C, respectively (table 2).

Table 2. Phenological

evaluation of “Cabernet Franc”, “Merlot”, “Semillón” y “Tannat” (Vitis

vinífera L.) in Tandil, Buenos Aires province, from September to February.

Tabla

2. Periodos de evaluación fenológica

de las 4 variedades de Vitis Vinifera L. plantadas en Tandil, Buenos

Aires.

Rainfall (mm), mean (Tm),

absolute maximum (Tmax), and minimum (Tmin) temperatures (°C) recorded in each

growth cycle.

Precipitaciones (mm), Temperaturas

medias (Tmed), máximas (Tmax) y mínimas (Tmin) absolutas (°C) registradas en

cada ciclo de crecimiento.

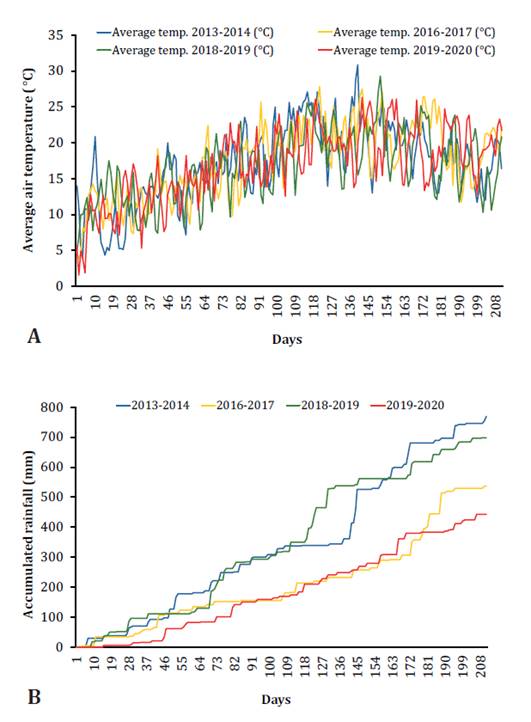

Temperatures below BT (10°C) were recorded in all production

cycles (figure

2),

primarily between budburst and flowering onset (BB-FO). During November,

coinciding with FO, average maximum temperature was 25°C in all four periods,

with an average minimum temperature of 10°C. These conditions fell within the

range between BT (10°C) and OT (25°C) (figure 2).

Figure 2. A. Average air temperature

(°C) and B. Accumulated

rainfall (mm) from September 1 to the end of March in four seasons, for

Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Semillón, and Tannat grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.)

in Tandil, Buenos Aires province, Argentina.

Figura

2. A. Temperaturas medias del aire

(°C) y B. Precipitaciones acumuladas (mm), desde el 1 de septiembre hasta

finales de marzo en cuatro temporadas, para las variedades de vid Cabernet

Franc, Merlot, Semillón y Tannat (Vitis vinifera L.) en Tandil,

provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

In December, average maximum temperature reached 29°C during

FO-VO and 20°C when calculated as mean temperature considering the four growth

cycles. Finally, temperatures above TT (35°C) were recorded in all four

production cycles, particularly during 2013-2014, on December 23, 24, 28, and

29, and January 6, 15, 17, and 18. Noticeably, total rainfall recorded in 2013

was 762.6 mm, below the historical average of 30 years (889 mm), while in 2014

was 1402 mm, significantly above historical average for Tandil. Table 2 shows

442 mm total rainfall in the last cycle (2019-2020), and during winter before

BB, minimum temperature of -7.8°C and rainfall of 18 mm.

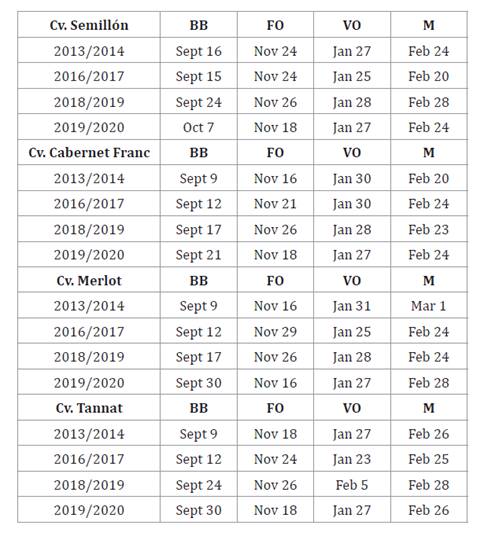

The complete cycle from BB to M lasted, on average, 161 days for

Cabernet Franc, 162 days for Merlot, 161 days for Tannat, and 154 days for

Semillón. No differences were observed between varieties (p > 0.05). Table 3 details

phenological dates for all four seasons.

Table 3. Phenological

dates for Semillón, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, and Tannat varieties, recorded

during four growing seasons: 2013 - 2014, 2016 - 2017, 2018 - 2019, and 2019 -

2020, in Tandil, Buenos Aires province.

Tabla

3. Fechas de los estadios fenológicos

observados en las variedades: Semillón, Cabernet Franc, Merlot y Tannat,

registrados durante 4 ciclos de cultivo: 2013 - 2014, 2016 - 2017, 2018 - 2019

y 2019 - 2020, en Tandil, Buenos Aires.

Budburst (BB), flowering onset

(FO), veraison onset (VO), and berry softening (M).

Los eventos fenológicos registrados

fueron inicio de la brotación (IB), inicio de la floración (IF), inicio del

envero (IE), y ablandamiento de yemas (M).

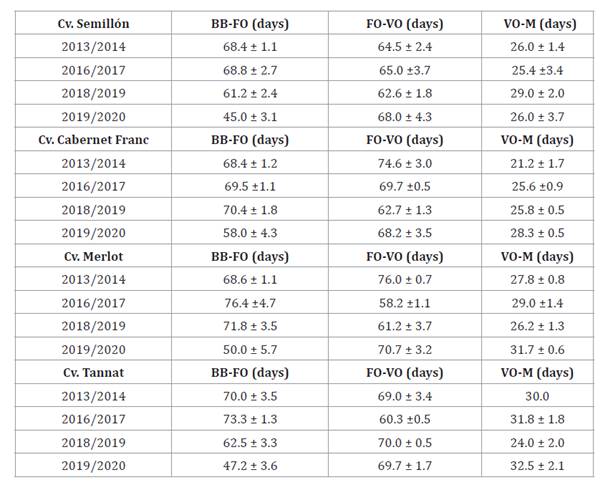

Methods 2.2 and 3

showed the most precise heat summation adjustments considering the whole cycle

in Tannat, Semillón, and Cabernet Franc, given lower standard errors (SE)

obtained in the FO-VO subperiod (table 4).

Table 4. Mean

duration of each subperiod (BB-FO, FO-VO, and VO-M, in days), + standard

deviation.

Tabla

4. Duración media de cada subperiodo en días, con su

desvío estándar, IB-IF (días), IF-IE (días), IE-M (días).

The table the average duration of

each subperiod in days, along with its standard deviation: BB-FO (days), FO-VO

(days), VO-M (days).

La tabla expresa la duración media

de cada subperiodo en días, con su desvío estándar, IB-IF (días), IF-IE (días),

IE-M (días).

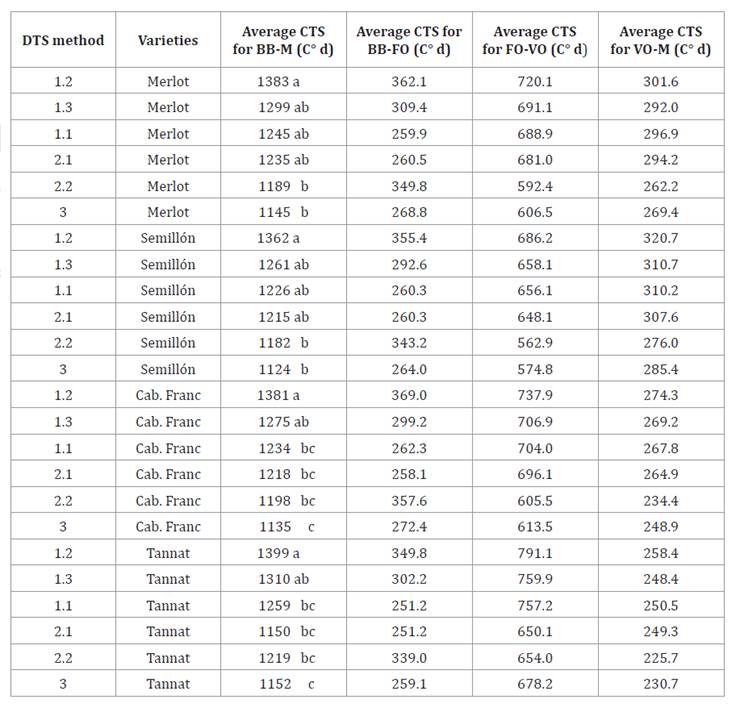

These methods did

not statistically differ from each other (p > 0.05) but did differ from

method 1.2 for all varieties (table 5). Considering method 2.2, CTS for Tannat, Semillón, and

Cabernet Franc were 1219, 1182, and 1198°C d, respectively, with SE values of

13.5, 31.5, and 11.78°C d. In contrast, when using method 3, CTS were 1152,

1124, and 1135 C° d, respectively, with SE values of 28.7, 44.8, and 28.1 C° d

(table

5).

For Merlot, method 3 provided the best adjustment (lowest SE), with 1145 C° d

CTS and an SE of 30.4 C° d. For Cabernet Franc and Tannat, medium and medium-late

maturing varieties respectively, method 3 also showed a statistical difference

of 1.3 (p < 0.05) compared to method 2.2 (table 5).

Table 5. Average

cumulative thermal sum (CTS) calculated for each subperiod (BB - FO, FO - VO,

and VO - M) and the BB-M period for the four varieties by six methods of

calculation of daily thermal sum (DTS).

Tabla

5. Suma térmica acumulada (STA) media

calculada para cada subperíodo (IB - IF, IF - IE, IE - M) y para el período IB

- M, para las 4 variedades, utilizando los 6 métodos de cálculo de la suma

térmica diaria (STD).

Different letters in columns

indicate statistical differences (p > 0.05).

Valores en las columnas seguidos de

la misma letra, no difieren entre sí por la prueba de Tukey (p > 0,05).

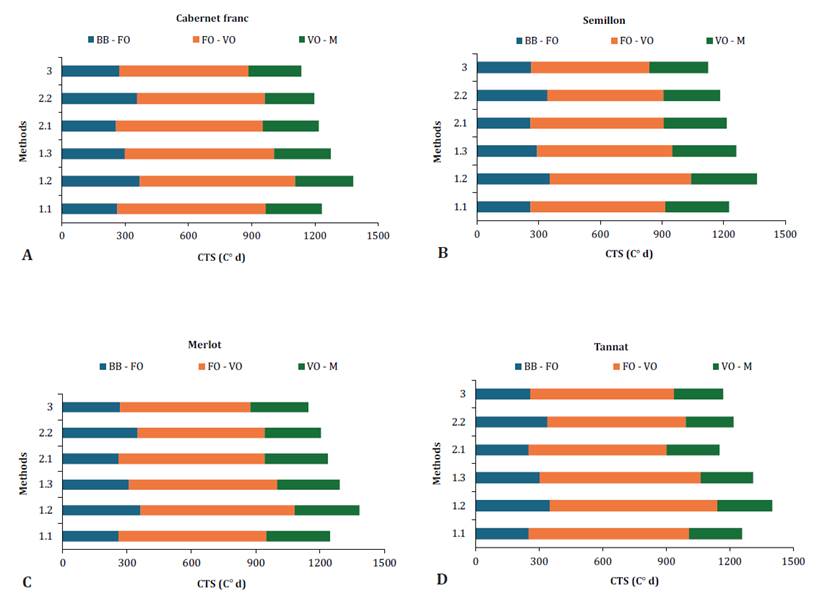

Thermal demands for each subperiod were also calculated after

the six thermal summation methods (figure 3 and figure

4).

Noticeable trends were observed among thermal sums for the four varieties, particularly

in the first subperiod (BB-FO), where methods 2.2 and 1.2 had higher CTS values

than the other methods (figure

3).

Figure 3. Cumulative

thermal sum (CTS, C° d) calculated for each subperiod: budburst to flowering

onset (BB-FO), flowering to veraison (FO - VO), and veraison to berry softening

(VO - M), by six methods (1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, and 3) estimating STD in

Cabernet Franc, Semillón, Merlot, and Tannat, in Tandil, Buenos Aires province.

Figura

3. Suma térmica acumulada (STA, °C d)

calculada para cada subperíodo: inicio de la brotación - inicio de la floración

(IB - IF), inicio de la floración - inicio del envero (IF - IE), inicio del

envero - ablandamiento de bayas (IE - M), utilizando seis métodos (1.1, 1.2, 1.3,

2.1, 2.2, y 3), estimando la STA en las variedades Cabernet Franc, Semillón,

Merlot y Tannat, en Tandil, provincia de Buenos Aires.

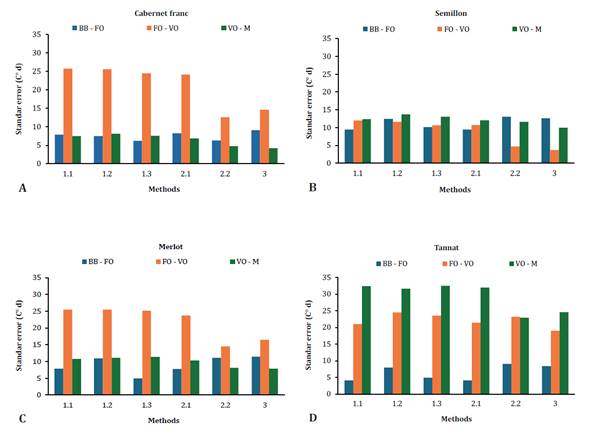

Figure 4. Standard

error (SE) of cumulative thermal sum (CTS, C° d) for each subperiod: budburst

to flowering (BB - FO), flowering to veraison (FO - VO) and veraison to berry

softening (VO - M). Six methods (1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, and 3) estimated

daily thermal sum (DTS) in Cabernet Franc, Semillón, Merlot, and Tannat in

Tandil, Buenos Aires province.

Figura

4. Error estándar (ES) de la suma

térmica acumulada (STA, °C d) para cada subperíodo: inicio de la brotación -

inicio de la floración (IB - IF), inicio de la floración - inicio del envero

(IF - IE), inicio del envero - ablandamiento de bayas (IE - M). Seis métodos (1.1,

1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2 y 3) estimaron la suma térmica diaria (STD) en las

variedades Cabernet Franc, Semillón, Merlot y Tannat en Tandil, provincia de

Buenos Aires.

These methods assume that when minimum temperatures are lower

than or equal to BT, minimum temperature equals BT and overestimates DTS and

CTS, especially in cold months with temperatures below BT. Method 2.1 resulted

in the lowest SE in Tannat and Semillón, with CTS values of 251.2 ± 16.6 C° d

and 260.3 ± 37.9 C° d, respectively.

In Semillón, no

difference was found among methods (p > 0.05), whereas in Tannat, however,

method 2.1 differed from methods 1.2 and 2.2 (p < 0.05). In Cabernet Franc,

methods 1.3 and 2.2 yielded similar SE values (6.2°C d), with CTS 300 C° d and

357 C° d, respectively, while in Merlot method 1.3 yielded a lower SE (figure 4), and no

differences with methods 2.2 and 3 (p > 0.05). Overall, methods 2.2 and 1.2

had significantly (p > 0.05) higher CTS values for this subperiod (BB - FO),

while method 2.1 yielded the lowest CTS for Tannat and Semillón. Additionally,

Tannat had a significantly different CTS calculated using method 2.1 from the

estimated using methods 1.2 and 2.2 (p < 0.05). Although these variations

between methods showed no differences for most varieties, they suggest that

calculation method influences CTS estimation. Considering Cabernet Franc and

Merlot, BB occurred on September 15 and 17, respectively, averaging four

observation cycles (table

3).

In other regions of South America, such as southern Brazil, BB for Merlot and

Cabernet Franc occurs around September 13 (26). Additionally,

during 2018-19 and 2019-20, a two-week delayed BB was observed compared to

previous years (table

3).

This delay could be attributed to the lower temperatures recorded toward the

end of winter, along with lower precipitation (figure 2), considering

varietal BB phenological pattern is primarily influenced by air temperature (26).

The longest

subperiod (63 - 91 days) with the highest thermal sum requirement was FO-VO, in

all four varieties. Minimum SE for this subperiod was recorded for methods 2.2

and 3. Considering Merlot, Cabernet Franc, and Tannat, no statistical

differences were observed with the other methods (figure 4). However, for

Semillón, methods 2.2 and 3 showed differences in SE (figure 4) and CTS (table 4) compared to

methods 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 (p < 0.05). Merlot had CTS ± SE of 592.2 ± 14.5 C°

d with method 2.2 and 606.5 ± 16.4 C° d with method 3. Semillón, showed 562.9 ±

4.7 C° d with method 2.2 and 574.8 ± 3.7 C° d with method 3. Cabernet Franc had

CTS 605.5 ± 12.6 C° d with method 2.2 and 613.5 ± 14.6 C° d with method 3.

Finally, CTS in Tannat was 662.5 ± 19.0 C° d with method 3. Considering Tannat,

all six methods showed high SE (figure 4).

The VO-M subperiod

showed no statistical differences among methods (p > 0.05) or the four

varieties. However, method 3 yielded the best fit in three varieties (figure 4). In detail, CTS ±

SE for Merlot, Cabernet Franc, and Semillón were 269.4 ± 7.9 C° d, 248.9 ± 4.2

C° d, and 285.4 ± 10.0 C° d respectively. Instead, in the VO-M subperiod,

Tannat showed higher SE than the other varieties while, with method 2.2, it

obtained the minimum SE (figure

4)

with CTS of 225.7 ± 24.6 C° d. This late variety had a delayed VO in the last

two cycles (table

3).

Between February 20 and March 1, 50% of the plants of all varieties (table 3) were at sub-stage

89. Harvesting occurred later, particularly in the intermediate to late

varieties. As latitude increases, more days are needed to reach a particular

phenological stage (3).

Methods 1.1, 1.2,

and 1.3 generated higher SE values for the four varieties. This lower

methodological efficiency in representing thermal accumulation has been

previously reported in southern Brazil (49). These three

methods, based only on BT, showed higher variability (high SE) in CTS

estimation than methods considering OT (methods 2.1 and 2.2) and TT (method 3).

In other crops like wheat, Rosa et al. (2009) found that methods

incorporating daily minimum and maximum air temperature to cardinal

temperatures, improved phenological simulation. Our results indicate greater

accuracy in calculating the thermal sum via methods including OT and TT in

addition to BT. Therefore, we discourage methods based solely on the BT,

especially considering that, during summer, higher temperatures can affect

plant metabolism (45, 49).

These results

suggest that, concerning grapevine development and climate change scenarios,

simulations should use methods 2.1, 2.2, and 3. This is particularly relevant

for Buenos Aires and its frequent extreme climatic events (6). Future scenarios

predict increasing average air temperature in several regions of the planet (19), with negative

consequences for viticulture (52). This acceleration

of climate change invalidates old phenological calculations based on number of

days (8, 22). Recent studies have shown

significant correlations between temperature increase and earlier beginning of

several stages in grapevine (1), with shortened

phenological stages (3, 20, 41). Some prominent

phenological changes suggest a significantly reduced anthesis-ripening duration

(26). Besides reduced

vine growth and yields, other possible undesirable implications for the wine

industry include changes in wine quality (11,

37, 50, 52). In this context, considering that grapevine phenology is a

crucial indicator of environmental impacts (7), accurate

estimations of thermal requirements based on cardinal temperatures can be

beneficial, regardless of the time required to satisfy them (33).

Considering methods 2.2 and 3, both demonstrating the lowest SE

in the CTS, the varieties evaluated exhibited no statistical differences in

thermal requirements during FO-VO and VO-M. Both methods estimated SE from 0.77

to 1.66 days for FO-VO and from 0.47 to 1.47 days for VO-M for Cabernet Franc,

Merlot, and Semillón, indicating relatively low dispersion compared to the

other four methods, where SE was twice higher. For Tannat, SE was two days,

using these methods and approximately four days with the remaining four

methods, in both subperiods. In BB-FO, the lowest SE was 1.18 days by method

2.2 for Cabernet Franc, while SE for the other varieties, was higher.

Our results provide

information on thermal requirements of four grapevine varieties at different

phenological stages in the region of Tandil, center Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The use of degree-days improved phenological prediction, compared to other

approaches considering days between phenological events (23). Considering the

onset of autumn in our region, high humidity levels and low evapotranspiration

may negatively affect fruit quality. Therefore, harvest should occur before the

end of March. Future research should determine thermal requirements for

maturity and harvest, contributing to climate risk mitigation and definition of

optimal harvest time.

Conclusion

According to method

3, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Semillón, and Tannat grown in Tandil require 1145,

1135, 1125, and 1153 C° d, respectively, to reach BBCH sub-stage 85.

The period between

budburst and flowering onset showed the highest variability in thermal sum when

comparing six methods for thermal requirement determination.

We conclude that

methods 2.2 and 3 most accurately estimate cumulative daily heat summation in these

varieties, in Tandil, using optimum temperature and upper threshold temperature

for Vitis vinifera L.

Method 2.2 was accurate in this specific region, given the low

frequency of temperatures above 35°C during the periods evaluated. Considering

changes in climatic events in the center of Buenos Aires, we recommend models

capable of recording daily variations in maximum and minimum temperatures.

Further research will determine thermal requirements of different grapevine

varieties in this region, especially between veraison and harvest.

1.

Alikadic, A.; Pertot, I.; Eccel, E.; Dolcia, C.; Zarbo, C.; Caffarra, A.; De

Filippi, R.; Furlanello, C. 2019. The impact of climate change on grapevine

phenology and the influence of altitude: A regional study. Agric. For.

Meteorol. 271: 73-82.

2.

Almanza, P.; Serrano, P.; Fischer, G. 2012. Manual de viticultura tropical.

Grupo Imprenta y Publicaciones UPTC. Tunja. Colombia. 120 p.

3.

Antonacci, D.; Ramos, J.; Dalla, J. 2001. Infuenza della disponibilitá termica

sulle manifestazioni fenologiche della vite in diverse aree di produzione dei

due emisferi. Frutticoltura e di ortofloricoltura. 63(12): 65-72.

4.

Anzanello, R.; Souza, P. V. D. de; Coelho P.F. 2012. Fenologia, exigência

térmica e produtividade de videiras ‘Niagara Branca’, ‘Niagara Rosada’ e

‘Concord’ submetidas a duas safras por ciclo vegetativo. Revista Brasileira de

Fruticultura. 34: 366-376.

5.

Bem, B. P. de; Bogo, A.; Everhart, S.; Casa, R. T.; Gonçalves, M. J.; Marcon

Filho, J. L.; Cunha, I. C. da. 2015. Effect of Y-trellis and vertical shoot

positioning training systems on downy mildew and botrytis bunch rot of grape in

highlands of southern Brazil. Scientia Horticulturae. 185: 162-166. DOI:

10.1016/j.scienta.2015.01.023

6.

Confalone, A.; Navarro, M.; Vilatte, C.; Aguas, L.; Lázaro, L.; Mestelan, S.;

Sau, F. 2016. Parametrización y uso del modelo CROPGRO -soja en Azul, Buenos

Aires. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de

Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 48(1): 49-64.

7.

Bernardo, S.; Dinis, L. T.; Machado, N.; Moutinho-Pereira, J. 2018. Grapevine

abiotic stress assessment and search for sustainable adaptation strategies in

Mediterranean-like climates. A review. Agron. Sustain. 38(66).

8.

Bock, A.; Sparks, T.; Estrella, N.; Menzel, A. 2011. Changes in the phenology

and composition of wine from Franconia, Germany. Clim. Res. 50: 69-81.

9.

Del Barrio, R. A; Gallo, S. L.; Martin, D. M. 2016. Aspectos bio y

agroclimáticos del cultivo de vid para vinificar en el Valle Inferior del Río

Negro. RIA. Rev. Investig. Agropecu. 42(3): 283-290.

http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1669-

23142016000300008&lng=es&nrm=iso.

10.

Di Rienzo, J. A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.;

Robledo, C. W. 2019. InfoStat versión 2019. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat,

FCA. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Argentina. http://www.infostat.com.ar

11.

Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A. C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J. A. 2012. Future

scenarios for viticultural zoning in Europe: Ensemble projections and

uncertainties. Int. J. Biometeorol. 57: 909-925.

12.

Gilmore, E.; Rogers, J. S. 1958. Heat units as a method of measuring maturity

in corn. Agron. J. 50: 611-615.

13.

Godoy Baduino, C. A.; Gancedo Desgens, E. 2022. Aptitud vitícola del sudeste

bonaerense en base a índices bioclimáticos. Rev. Facultad de Agronomía UBA.

42(2): 7-12.

14.

Gomez Talquenca, S.; Lanza Volpe, M.; Setien, N.; Gracia, O.; Grau, O. 2023.

Serological relationships among strains of grapevine leafroll-associated virus

4 reflect the evolutive behavior of its coat protein gene. Revista de la

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 55(1): 104-114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.100.

15.

Gris, E. F.; Burin, V. M.; Brighenti, E.; Vieira, H.; Bordignon-Luiz, M. T.

2010. Fenología y maduración de las variedades de Vitis vinifera L. de

uva en São Joaquim, sur de Brasil: una nueva región de cultivo de la vid en

América del Sur. Cien. Inv. Agr. 37(2): 61-75.

16.

Hidalgo, L. 2002. Tratado de viticultura general. Ediciones Mundi-Prensa,

Madrid.

17.

Ibacache G. A. 2008. Cómo influye la temperatura sobre la época de cosecha en

vides [en línea]. Tierra Adentro. 81: 8-10.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14001/6416 (Consultado: 30 abril 2024).

18.

Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura. 2022. Informe elaborado por el

laboratorio estadístico del Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura. Registro de

viñedos y superficie. Mendoza.

19.

IPCC 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of

working Group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel

on climate change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van

Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A.

Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press.

Cambridge. UK and New York. NY. USA. DOI: 10.1017/9781009157926

20.

Jones, G. V.; Alves, F. 2012. Impact of climate change on wine production: A

global overview and regional assessment in the Douro Valley of Portugal. Int.

J. Glob. Warm. 4: 383-406.

21.

Jubileu, B. S.; Sato, A. J.; Roberto, S. R. 2010. Caracterização fenológica e

produtiva das videiras ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ e ‘Alicante’ (Vitis vinifera L.)

produzidas fora de época, no norte do Paraná. Revista Brasileira de

Fruticultura. 32: 451-462.

22.

Labbé, T.; Pfister, C.; Brönnimann, S.; Rousseau, D.; Franke, J.; Bois, B.

2019. The longest homogeneous series of grape harvest dates, Beaune 1354-2018,

and its significance for the understanding of past and present climate. Clim.

Past. 15: 1485-1501. DOI: 10.5194/ cp-15-1485-2019

23.

Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, W. 2023. Control temperature of greenhouse

for higher yield and higher quality grapes production by combining STB in

situ service with on time sensor monitoring. Heliyon. 9(2): e13521.

24.

Lorenz, D. H.; Eichhorn, K. W.; Blei-Holder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber,

E. 1994: Phänologische Entwicklungsstadien der Weinrebe (Vitis vinifera L.

ssp. vinifera). Vitic. Enol. Sci. 49: 66-70.

25.

Lucas, D. D. P.; Streck, N. A.; Bortoluzzi, M. P.; Trentin, R.; Maldaner, I. C.

2012. Temperatura base para emissão de nós e plastocrono de plantas de

melancia. Revista Ciência Agronômica. 43: 288-292. DOI:

10.1590/S1806-66902012000200011

26.

Mandelli, F.; Berlato, M. A.; Tonietto, J.; Bergamaschi, H. 2003. Fenologia da

videira na Serra Gaúcha. Pesquisa Agropecuária Gaúcha. 9: 129-144.

27.

Moriondo, M.; Bindi, M. 2007. Impact of climate change on the phenology of

typical Mediterranean crops. Ital. J. Agrometeorol. 3: 5-12.

28.

Moura, M. S. B. de; Brandao, E. O.; Soares, J. M.; Donosco, C. S.; Silva, T. G.

F. da; Souza, L. S. B. 2007. Exigência térmica e caracterização fenológica da

videira Cabernet Sauvignon no Vale São Francisco, Brasil. Congreso

Latinoamericano de Viticultura y Enología. Mendoza. Seduciendo al consumidor de

hoy. Mendoza: IVV: CLEIFRA: SECYT. 2007.

29.

Nagata, R. K.; Scarpare Filho, J. A.; Kluge, R. A.; Nova, N. A. V. 2000.

Temperatura base e soma térmica (graus-dia) para videiras ‘Brasil’ e

‘Benitaka’. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, Cruz das Almas. 22(3): 329-333.

30.

Nikolaou, K. E.; Chatzistathis, T.; Theocharis, S.; Argiriou, A.; Koundouras,

S.; Zioziou, E. 2022. Cultivars Effects of chromium toxicity on physiological

performance and nutrient uptake in two grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.)

growing on own roots or grafted onto different rootstocks. Horticulturae. 8(6):

493. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/horticulturae8060493

31.

Nikolaou, K. E.; Chatzistathis, T.; Theocharis, S.; Argiriou, A.; Koundouras,

S. 2023. Physiological and nutritional responses of ungrafted merlot and

cabernet sauvignon vines or grafted to 101-14 Mgt and 1103P rootstocks exposed

to an excess of boron. Horticulturae. 9(4): 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/

horticulturae9040508

32.

Oliveira, M. 1998. Calculation of budbreak and flowering base temperatures for Vitis

vinifera cv. Touriga Francesa in the Douro Region of Portugal. Am. J. Enol.

Vitic. 49: 74-78.

33.

Parker, A. K.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Gény, L.; Spring, J. L.; Destrac,

A.; Schultz, H.; Molitor, D.; Lacombe, T.; Graça, A.; Monamy, C.; Stoll, M.;

Storchi, P.; Trought, M. C. T.; Hofmann, R. W.; van Leeuwen, C. 2020.

Temperature-based grapevine sugar ripeness modelling for a wide range of Vitis

vinifera L. cultivars. Agric. For. Meteorol. 285-286:107902. doi:

10.1016/j. agrformet.2020.107902

34.

Paula, G. M. de; Streck, N. A. 2008. Temperatura base para emissão de folhas e

nós, filocrono e plastocrono das plantas daninhas papuã e corriola. Ciência

Rural. 38: 2457-2463.

35.

Pedro Júnior, M. J.; Sentelhas, P. C.; Pommer, C. V.; Martins, F. P. 1994.

Determinação da temperatura-base, graus-dia e índice biometeorológico para a

videira ‘Niagara Rosada’. Revista Brasileira de Agrometeorologia, Santa Maria.

2: 51-56.

36.

Radünz, A. L.; Schöffel, E. R.; Borges, C. T.; Malgarim, M. B.; Pötter, G. H.

2015. Necessidades térmicas de videiras na região da Campanha do Rio Grande do

Sul - Brasil. Ciência Rural. 45: 626-632. DOI: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20140134

37.

Reyes, M. 2015. Informe proyecto “Aseguramiento de la sustentabilidad de la

viticultura nacional frente a los nuevos escenarios que impone el cambio

climático”. Código 502063-70. Centro Regional de Investigación Raihuen.

38.

Reynier, A. 2005. 6ª ed. Manual de Viticultura. Mundi-Prensa. Madrid. España.

497 p.

39.

Roberto, S. R.; Sato, A. J.; Brenner, E. A.; Jubilei, B. S.; Santos, C. E.;

Genta, W. 2005. Caracterização fenológica e exigência térmica (graus-dia) para

a uva ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ em zona subtropical. Acta Scientiarum Agronomy.

27(1): 183- 187.

40.

Rosa, H. T.; Walter, L. C.; Streck, N. A.; Alberto, C. M. 2009. Métodos de soma

térmica e datas de semeadura na determinação de filocrono de cultivares de

trigo. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira. 44: 1374-1382.

41.

Santos, C. E. dos; Roberto, S. R.; Sato, A. J.; Jubileu, B. da S. 2007.

Caracterização da fenologia e da demanda térmica das videiras ‘Cabernet

Sauvignon’ e ‘Tannat’ para a região norte do Paraná. Acta Scientiarum.

Agronomy. 29: 361‑366.

42.

Sato, A. J.; Jubileu, B. da S.; Assis, A. M. de; Roberto, S. R. 2011.

Fenologia, produção e composição do mosto da ‘Cabernet sauvignon’ e ‘Tannat’ em

clima subtropical. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura. 33: 491‑499. DOI: 10.1590/S0100‑29452011005000079

43.

Stenzel, N. M. C.; Neves, C. S. V. J.; Marur, C. J.; Scholz, M. B. d. S.;

Gomes, J. C. 2006. Maturations curves and degree-days accumulation for fruits

of “Folha Murcha” organge trees. Sci. Agric. 63(3): 219-225.

44.

Streck, N. A.; Tibola, T.; Lago, I.; Buriol, G. A.; Heldwein, A. B.; Schneider,

F. M.; Zago, V. 2005. Estimativa do plastocrono em meloeiro (Cucumis melo L.)

cultivado em estufa plástica em diferentes épocas do ano. Ciência Rural. 35:

1275 1280.

45.

Streck, N. A.; Alberto, C. M. 2006. Estudo numérico do impacto da mudança climática

sobre o rendimento de trigo, soja e milho. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira.

41: 1351‑1359.

46.

Streck, N. A.; Michelon, S.; Rosa, H. T.; Walter, L. C.; Bosco, L. C.; Paula,

G. M. de; Camera, C.; Samboranha, F. K.; Marcolin, E.; Lopes, S. J. 2007a.

Filocrono de genotipos de arroz irrigado em função da época de semeadura.

Ciência Rural. 37: 323‑329.

47.

Streck, N. A.; Paula, F. L. M. de; Bisognin, D. A.; Heldwein, A. B.; Dellai, J.

2007b. Simulating the development of field grown potato (Solanum tuberosum L.).

Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 142: 1‑11.

DOI: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.09.012

48.

Tesic, D.; Woolley, D. J.; Hewett, E. W.; Martin, D. J. 2001. Environmental

effects on cv Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.) grown in Hawke’s

Bay, New Zealand: 2. Development of a site index. Australian journal of grape

and wine research. 8(1): 27-35.

49.

Tomazetti, T. C.; Rossarolla, M. D.; Zeist, A. R.; Giacobbo, C. L.; Welter, L.

J.; Alberto, C. M. 2015. Fenologia e acúmulo térmico em videiras viníferas na

região da Fronteira Oeste do Rio Grande do Sul. Pesquisa Agropecuária

Brasileira. 50: 1033-1041.

50.

Van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Dubernet, M.; Duchêne, E.; Gowdy, M.;

Marguerit, E.; Pieri, P.; Parker, A.; De Rességuier, L.; Ollat, N. 2019. An

update on the impact of climate change in viticulture and potential

adaptations. Agronomy. 9: 514.

51.

Venios, X.; Korkas, E.; Nisiotou, A.; Banilas, G. 2020. Grapevine responses to

heat stress and global warming. Plants. 9(12): 1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9121754

52.

Villa Nova, N. A.; Pedro Jr, M. J.; Pereira, A. R.; Ometto, J. C. 1972.

Estimativa de graus-dia acumulados acima de qualquer temperatura base, em

função das temperaturas: máximas e mínimas. Caderno de Ciências da Terra. São

Paulo. 30: 1-8.

53.

Villaseca, S.; Novoa, R.; Muñoz. I. 1986. Fenología y sumas de temperatura en

24 variedades de vid. Agricultura Técnica. Chile. 46: 63-67.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14001/41010

54.

Zapata, D.; Salazar-Gutierrez, M.; Chaves, B.; Keller, M.; Hoogenboom, G. 2017.

Predicting key phenological stages for 17 grapevine cultivars (Vitis

vinifera L.). American Journal Enology and Viticulture. 68: 60-72. DOI:

10.5344/ajev.2016.15077

55.

Zeist, A. R.; Tomazetti, T. C.; Rossarolla, M. D.; Alberto, C. M.; Giacobbo, C.

L.; Welter, L. J. 2017. Plastochron index of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and

‘Chardonnay’ grapevines in Fronteira Oeste, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul,

Brazil. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira. 52(4): 244-251. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2017000400004