Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Food

labeling in Argentina. Decoding impacts on the Argentine Food Code

Rotulación

y etiquetado de alimentos en el régimen argentino. El fenómeno de la

descodificación y su impacto en el Código Alimentario Argentino

Mauricio Buccheri1,

David Martín1

1Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Almirante Brown 500. M5528AHB. Chacras de Coria. Mendoza. Argentina.

* ticio2006@gmail.com

Abstract

This work aims to

analyze the characteristics of the legislative codification technique in

Argentina, and whether, since the enactment of the Food Code to the present,

this technique has been affected by a decoding normative evolution, considering

the food labeling regime a particular study case. As a result, three lines of

legislative alteration or modification distorting the mentioned technique re

identified. This generates inconsistencies and ambiguities in the legislation,

and consequent negative effects on the application, compliance and

understanding of food regulations in the industry.

Keywords: codifying,

decoding, food code, legislative technique, labeling

Resumen

Este trabajo

procura analizar las características de la técnica legislativa de la

codificación en el régimen de alimentos de Argentina y si, desde la

promulgación del Código Alimentario a la actualidad, dicha técnica ha sido

afectada por una evolución normativa descodificante, tomando como caso de

análisis particular el régimen de rotulado de alimentos. Como resultado, se

identifican tres líneas de alteración o modificación legislativa que desnaturalizan

claramente a la referida técnica, lo que genera necesariamente incoherencias y

ambigüedades en la legislación, con los consiguientes efectos negativos en la

aplicación, cumplimiento y comprensión de las normativas en la industria

alimentaria.

Palabras clave: codificacion,

descodificacion, código alimentario, técnica legislativa, rotulado

Originales: Recepción: 29/12/2023 - Aceptación: 26/08/2024

Introduction

Since 1969,

Argentina has adopted a food regime based on the legislative codification

technique. Law 18248 approves a Food Code ordered in Annex I of Decree 2126/71.

This legislative

regulation strategy prioritizes a single legal text systematized in an organic

unit through a specific methodology, which provides internal coherence to the

set of regulations integrated as a universe. Codifying is not collecting or

compiling various laws issued on the subject, but achieving a legal text

systematized by a single regulatory logic.

But since its

sanctioned date, the Argentine Food Code has been subject to multiple and

repeated internal reforms, motivated by various needs and causes, also

motivating and responding to public policies of each era – which have not always

had the same objectives. Numerous special laws on food have also been issued.

As external regulations, these laws separately complement the Code.

Even in the legal

harmonization generated from the regional integration process of the Southern

Common Market (MERCOSUR - acronym in Spanish), numerous rules on food have been

issued that -when incorporated into the Code- have impacted its regulations.

This situation

raises concern as to whether the proliferation of norms -often disorderly or

uncoordinated-occurring for more than half a century has affected the

organicity and clarity of the Code as a whole. In short, if such an impact had

occurred, the initial legislative technique that organizes the Food Code would

have been devalued to the detriment of legal efficiency and effectiveness, and

the legal security that the regulatory system must provide.

This work seeks to

analyze the characteristics of the legislative codification technique in the

Argentine food regime and state whether, since the enactment of the Food Code

to the present day, this technique has been affected by a decoding normative

evolution, taking labeling regime as study case.

To this end, it is

hypothesized that the lack of respect for the technique of legislative

codification in the partial reforms of the Argentine Food Code and other food

regulations issued in the last half-century can generate inconsistencies and

ambiguities in the legislation, which in turn can have negative effects on the

application, compliance and understanding of regulations in the food industry.

Materials

and methods

The article

presents a qualitative analysis of the decoding phenomenon in the Argentine

Food Code; particularly considering the labeling regime stipulated in Chapter V

of this Code, and the impact caused therein by formal and material decoding

processes. To this end, the intrinsic modifications produced in Code and the

incidence of external laws, are individualized.

An observational methodological design with a

descriptive-explanatory scope analyzed the Argentine Food Code considering two

well-differentiated phases.

The first phase

focuses on specifying the characteristics of codification as a legislative

technique for the Argentine Food regime, and the decoding risk due to normative

modifications developed without considering such legislative technique. The

second phase identifies the legal modifications in the labeling regime

-internal and external to the Code text- and the fragmentation caused to the

current regime.

Results

The

argentine food code as legislative technique

The legal approval

of a “Code” implies a legislative technique systematically organizing the set

of regulations on a subject in a single legal text. “Codifying” means much more

than compiling existing regulations; it gives organic unity to a set of norms endowed

with intimate cohesion due to their meaning (12), simplifying and

unifying their interpretation and application for the benefit of legal

effectiveness, efficiency, and certainty.

Under this concept,

dictating a code is not a mere compilation of anarchic precepts among

themselves, but rather implies a coherent legal text that requires

classification, distribution, and coordination of the materials with which it

is constructed (20). For this reason,

the legislative technique of codification should not be confused with mere

“collections,” “indexes,” “compilations,” or “recompilations” of laws by

subject matter or historical era presented in order in a repertoire, or with

“digests” which the current texts present in a similar way but without an

organic character -typical of codification- that systematizes its content as a

unit (7, 22).

Such repertoires

and digests, although they allow the identification of the regulations that

have been issued or even their state of validity, do not guarantee a level of

coherence that allows overcoming shortcomings such as inflation and regulatory

pollution, that is, the overabundance and redundancy of laws that make the

regime unclear. As Campos

(2018)

observes, the disorderly proliferation of norms devalues the rule of law and

generates a significant lack of legal security.

A code, on the

other hand, is a rationally formed legal text based on harmonious and coherent

principles (19). It implies a

legislative technique based on a methodology that provides coherence and order

to a universe of institutions and norms formed as a single legal instrument,

ensuring organicity and clarity as a whole (5).

Codified

regulations make it easier to verify the current law, offering clarity,

concision and legal certainty (7, 21), helping to avoid

antinomies and other normative failures to be overcome by scope interpretation,

with the consequent interpreter bias that generates inconsistencies and

ambiguities on application, compliance and understanding of regulations.

The food regime in

Argentina has been implemented under the legal technique of codification since

1969, with the sanction of Law 18248 by which the Argentine Food Code was

approved and put into effect. At that time, this Code systematized in a single

regime the right to food, which applies to any person, commercial firm or

establishment that produces, divides, conserves, transports, sells, displays,

imports or exports food, condiments, beverages or raw food materials and

additives.

The food regulation contained in this Code is organized into

twenty-two chapters comprising 1417 articles. Seven chapters establish

transversal regulations for the entire food industry -(I) General Provisions;

(II) Food Factories and Businesses; (III) Food Products; (IV) Utensils,

Containers, Packaging, Devices and Accessories; (V) Food Labeling and

Advertising; (XX) Official Analytical Methodology; (XXI) Procedures-. The

remaining chapters establish specific regulations on the different types of

foods and food products -(VI) Meat and Related Foods; (VII) Fatty Foods, Food

Oils; (VIII) Dairy Foods; (IX) Farinaceous Foods: Cereals, Flours and

Derivatives; (X) Sugary Foods; (XI) Vegetable Foods; (XII) Hydric Beverages,

Water and Carbonated Water; (XIII) Fermented Beverages; (XIV) Spirits,

Alcohols, Distilled Alcoholic Beverages and Liquors; (XV) Stimulant or Fruitive

Products; (XVI) Correctives and Coadjuvants; (XVII) Dietary Foods; (XVIII) Food

Additives; (XIX) Flours, Concentrates, Isolates and Protein Derivatives; (XXII)

Miscellaneous-.

Finally, it should

be clarified that the same Code and its regulations (art. 2 Regulation approved

by Decree 2126/71) have contemplated specific cases in which the codification

yields specific regulations on wines and meats so that the Food Code –although

valid in such matters- only applies supplementarily. This situation was

initially anticipated as temporary in article 1411 of the original text ordered

by Decree 2126/71 (13), contemplating a

process of incorporation into the Code that was never finalized.

Modification

of the Food Regime and the Danger of “Decoding”

The eventual

modification of the Argentine Food Code requires legal reform, either by a new

law altering the content of the Argentine Food Code or establishing new

precepts without altering the Code.

However, and

without prejudice to the possibility of the legislative authority to enact new

regulations, article 20 of Law 18284 introduced a mechanism for permanent

updating of this norm, facilitating the incorporation of industry and science

advances. To this end, this provision delegated the administrative authority

with the power to keep the technical normative of the Code updated, being able

to resolve necessary modifications to be included in the codified text.

This legal

actualization technique has provided a marked dynamism to the regulation

following the contemporary concept of codification, which rejects the idea of

an immovable regime and promotes constant normative adaptation (11,

17). This allows its evolution at the pace and need of each era,

but always without losing internal coherence and systemic unity.

In this way, and

over time, the food regime has been subject to new regulations, some produced

through the actualization mechanism provided for in article 20 of the law

18284, with the administrative authority issuing resolutions substituting,

deleting or adding precepts. In this sense, Guajardo (1998) identifies that in

the first three decades of validity (between 1969 and 1998) the Food Code

presented more than 1000 changes implemented through more than 200 modifying

provisions. Updating this information, in the last two decades (1999 a 2022)

more than 300 amending provisions have modified the Code.

Besides the

aforementioned, there has been extensive legislative activity concerning food,

with special laws being issued for certain specific aspects, as the

fortification of salts (Law 17259) or flours (Law 25630), the regulation of

Slaughter Establishments (Law 22375), the gluten-free products regime (Law

26588), or more recently, the Healthy Eating Promotion regime (Law 27642).

An important impact

on food regulations has occurred due to the framework of the regional

integration process of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) initially

established by Argentine, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay in the Treaty of

Asunción of 1991, and to which Venezuela -currently suspended- and Bolivia -in

the accession process- later joined. Numerous requirements on food generated

within the scope of MERCOSUR have been incorporated through adjustments in the

Argentine Food Code. Guajardo (1998) observed that this sector of

community regulations has helped lead the unifying or harmonizing process among

the different countries. Legislative action in this area of regional

integration has significantly impacted the national food legislation.

This regional

integration and generated regulations are important not only since,

commercially, MERCOSUR increases the exchange of food products among parties

while constituting a great platform for food export (18), even to other

regions (4); but especially because trade

governance in the 21st century

is based on standards and regulations rather than on classic tariff

limitations. Integration agreements provide the opportunity for developing the

necessary regulatory framework (2).

Faced with the

various regulatory sources currently generating food norms, i.e. technical

adjustments to the Code, new laws on the subject and harmonization with the

regional integration process, it is opportune to analyze whether practices are

leading to a “decoding” or the breakdown of the unity of the Code due to the

proliferation of special laws at the rate of change on the issues to be

regulated (8).

Guajardo (1998) has long observed

that, although the Argentine Food Code is strictly the one approved by Law

18284 and Decree 2126/71, general regulations on food are much broader, and

therefore cannot be identified with the concept of Code. This implies matching

the legal rules in a way that an organic and systemic whole is created.

Although, according

to Guzmán

Britos (1993), the decoding of a regime can occur in different ways. On the

one hand, formal decoding occurs when special laws, foreign or external to the

Code, alter the unity of the legislation initially found in a single normative

text, generating dispersion and tension between such precepts. In this sense, Hinestrosa

Forero (2014) observes that perhaps, the special legislator should be

reproached for not having known or wanted to adapt the figures of the Code

capable of useful application to the new demands.

Considering

material decoding, modifications are introduced to the text of a Code itself,

although altering the system logic that it presents (14). This is, although

not every modification to the Code text implies decoding, those modifications

that break rationality, harmony and coherence, denaturalizing the Code

codification technique. In such cases, the Code is transformed -at least

partly- into a normative index, compilation or digest of non-systematized

normative precepts.

In order to analyze

whether the modifications in the food regime are generating a decoding process,

below we specify the impact of legal reforms focusing on the food labeling

regime.

Labeling

of food products

One topic in the

system of the Argentine Food Code is related to “Food Labeling and Advertising

Rules”, developed in Chapter V (articles 220 to 246).

The Codex

Alimentarius guidelines developed by FAO and WHO define labeling as “any tag,

brand, mark, pictorial or other descriptive matter, written, printed,

stenciled, marked, embossed or impressed on, or attached to a container of food

or food product” (10). In the regional

and local regime, Resolution GMC 26/01 -dictated within the scope of MERCOSUR

and incorporated into the Food Code- defines labeling as any label,

inscription, image or other descriptive or graphic material, written, printed,

stenciled, marked, engraved in high or low relief, adhered, superimposed or

fixed to the container of the prepackaged product.

Food labeling is a

fundamental tool in the communication of nutritional information, potentially

influencing consumer choices and eating habits. Information should be easy to

read and interpret (9).

One of the actions

proposed within the Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity, and Health

adopted by the World Health Organization in 2004 is to improve people’s ability

to make informed decisions about nutrition through useful, easy and

understandable labeling, promoting nutrition and health literacy (23).

In the

aforementioned guidelines of Codex Alimentarius developed by FAO and

WHO (1985), the name of the food, the list of ingredients, net content,

identification and address of production companies, country of origin, batch

identification, date and storage instructions are recommended as mandatory

content in the labeling regulations. They also specify situations in which

ingredients must be declared quantitatively, as well as when dealing with

irradiated foods.

Within food

labeling, the so-called nutritional labeling can be specified as a

particularity, in which -to inform the consumer- a description of the food

nutritional properties is provided. In certain regulations, these guidelines

are related to the preparation and nutrient content of a product without

indicating whether they are healthy products, making it necessary to interpret (16).

In this regard,

various countries have adopted consumer protection policies through the

implementation of front labeling laws, by which beyond the mere inclusion of

the nutritional information, they seek to limit the marketing of food products

with harmful components like saturated fats, added sugars, sodium or high

calories (1).

Fragmentation

and complexity of the food labeling regime

Beyond considering

the limited regulation in labeling terms of the Argentine food regime (6), a complex and

fragmented character also undermines the legislative technique of codification

adopted by Law 18284.

An initial and basic approach to the regulations on food

labeling was provided by Law 18284, a norm that, besides declaring the validity

of the Argentine Food Code, stipulated in article 19 that labels, packaging and

wrappers authorized according to said Code had to clearly and accurately

express their hygienic-sanitary, bromatological and commercial conditions.

According to the

text ordered by Decree 2126/71, the Argentine Food Code approved and dedicated

Chapter V to the “Food Labeling and Advertising Standards”, complemented with

other labeling requirements contained in the specific regime of the various

products regulated by the Code. Chapter V was composed of twenty-six precepts

(arts. 220 to 246). However, over time, various alterations have affected the

food labeling regime either through amending regulations or through external

regulations to the Code. These alterations coexist and must be applied in a

complementary manner.

Thus, Chapter V has

been the subject of numerous reforms through the updating administrative

mechanism provided in Article 20 of Law 18284, which has replaced and/ or

repealed its original text, or expanded it with new articles intercalated in

the original numbering as “bis”, “bis1”, “bis2”, “tris”, “quárter” and

“quinto”, “sexto” and “séptimo”. In this way, none of the twenty-six original

articles corresponding to the labeling regime in the ordered text by the Decree

2126/71, remain to date. Instead, twelve articles have been deleted by repeal,

fourteen have a replaced text, and eight new articles have been added through

reiteration (such as “bis”, “ter”, etc.) of the original numbering.

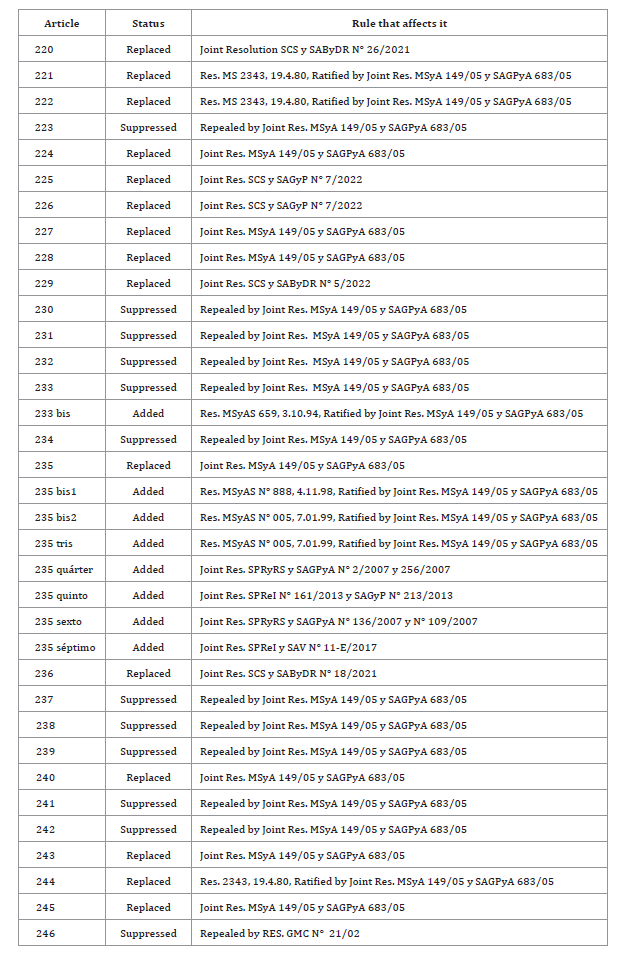

Table 1 details

modifications introduced by updating articles of the Argentine Food Code.

Table 1. Modifications

produced in Chapter V of the Argentine Food Code.

Tabla

1. Modificaciones producidas en el

Capítulo V del Código Alimentario Argentino.

These modifications

are not systematic, but rather respond to isolated and temporally distant

interventions, with dissimilar causes, purposes and contexts during 1980, 1994,

1998, 1999, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2013, 2017, 2021 and 2022. In this way,

although each modification does not alter the internal coherence of the norm

altogether eventually causes a fragmentation reducing the regime to a mere

juxtaposition of isolated precepts without an organic systematization.

This internal

fragmentation is strengthened since, through the same modifying mechanism, said

Chapter has also been expanded in content through the incorporation of various

resolutions issued within the scope of MERCOSUR. These resolutions were added

as part of the Code in an effort of regional legal harmonization, although

without any systematization or integration among articles, annexing the full

text of said community standards before the articles that make up the Chapter.

This technique corresponds to a simple normative compilation but not a

codification.

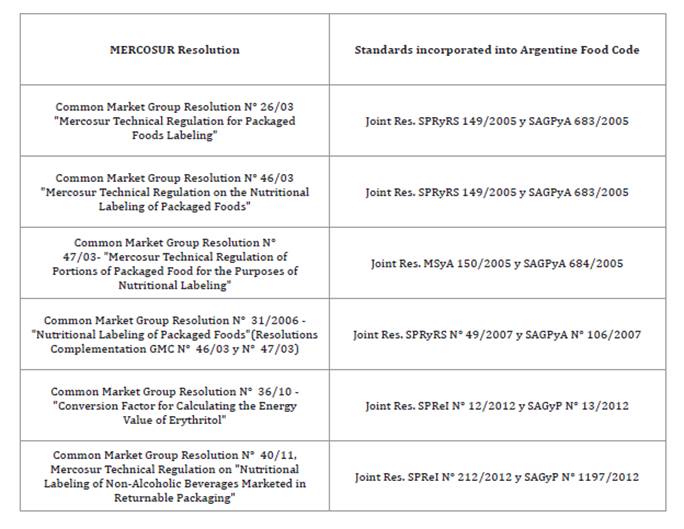

Thus, the labeling

regime includes the Common Market Resolutions N° 26/03 (“Mercosur Technical

Regulation for Packaged Foods Labeling”), N° 46/03 (“Mercosur Technical

Regulation on the Nutritional Labeling of Packaged Foods”), N° 47/03 (“Mercosur

Technical Regulation of Portions of Packaged Food for the Purposes of

Nutritional Labeling”), N° 31/06 (on “Nutritional Labeling of Packaged Foods”),

N° 36/10 (on “Conversion Factor for Calculating the Energy Value of Erythritol”),

N° 40/11 (MERCOSUR Technical Regulation on “Nutritional Labeling of

Non-Alcoholic Beverages Marketed in Returnable Packaging”); N° 01/12 (“MERCOSUR

Technical Regulation on Complementary Nutritional Information (Nutritional

Claims)”).

Table 2, details the

community standards sanctioned by MERCOSUR and incorporated in the Argentine

Food Code Chapter V.

Table 2. MERCOSUR

standards incorporated in the Argentine Food Code.

Tabla

2. Normas del MERCOSUR incorporadas al

Código Alimentario Argentino.

By completing this

regulatory framework, the legislative authority has also issued special laws

that, while regulating food matters parallely to the Code, contemplate labeling

aspects for some specific products.

Although some of these special laws have been integrated into

the Code through subsequent modifications (case of the labeling regime

stipulated by Law 17259 for enriched salts), in other cases, such precepts are

isolated, without systematization. Or even in some cases, they result

antinomian, as occurs with labeling regulations of enriched flours (Law 25630 y

and Decree 597/2003), labels and packaging on geographical indications and

designations of origin used for the commercialization of agricultural and food

origin products (Laws 25830 and 25966), whole milk powder supplied in food

programs (Law 25459 and its regulations), and gluten-free products (Law 26588).

The same occurs

with the legislation aimed at addressing Non-Communicable Diseases, with

substantial impact on the food labeling regime. Law 26905 -and its regulatory

Decree 16/17- contemplate, separately from the Food Code, that the Ministry of

Health includes health warning messages on containers in which salt (sodium

chloride) is marketed. Additionally, Law 27642 on Healthy Eating Promotion

(also known as the Front Labeling Law), despite updates of articles 225 y 226

of the Food Code established by Joint Resolution SCS y SAGyP N° 7/2022,

presents contents that exceed the codified guidelines.

Finally, certain

regulations issued by regulatory authorities of other normative systems have

dictated regulations on labeling that, omitting the regime stipulated in the

Argentine Food Code, increase the aforementioned decoding effect. This occurs

with Resolution 26/21 of the National Viticulture Institute concerning labeling

of wine industry products; or with Resolution 494/01 of the National Agri-Food

Health and Quality Service, labeling foods prepared with minced, ground or

sliced meat, and Resolution 5-E/2018 of the same entity on marketing of bulk

honey containers.

Conclusions

The Argentine Food

Regime was based on the legislative technique of codification, which implies a

regulatory strategy that enhances legal effectiveness, efficiency and legal

security by avoiding dispersed norms without internal coherence. At the same

time, codification does not necessarily imply static regulations, although its

evolution must safeguard internal coherence and systemic unity.

However, based on the study of labeling regulations and

modifications, it can be stated that the Argentine Food Code has three

legislative action lines in tension with the codification legislative

technique, affecting adoption and efficiency of the regulatory system.

On the one hand,

the continuous and numerous internal modifications to the Food Code carried out

individually in response to specific and independent problems, generate a clear

risk for internal coherence.

This process is

significantly enhanced by the notable deficiency in the legislative technique

with which legal harmonizations, inherent to the regional economic integration

process implemented in MERCOSUR, have been introduced into national law. In

these cases, community resolutions have been attached through mere

transcription, openly inconsistent with its methodology and articulation.

Incorporating such texts with no conception of organic unity reduced the Code

to norms without rational structure or cohesion.

A third line of the

undermining process of the Code is developed through the formal decoding and

enactment of various special laws and other regulations foreign to the

Argentine Food Code regime, obviously affecting the normative unity of

codifying.

The observed

situation allows us to affirm that since the enactment of the Food Code to the

present day, there has been a clear decoding normative evolution, which

necessarily generates inconsistencies and ambiguities in the legislation, with

the consequent negative effects on the application, compliance and

understanding of the regulations in the food industry.

To counteract the observed evolution, it becomes necessary to

revitalize the original legal strategy based on the codification of food

matters, which implies a review and readjustment of the current legal text so

that in the future it systematizes its content as a unit and regains lost

internal coherence.

1. Alfonso

González, I.; Romero Fernández, A. J.; Gallegos Cobo, A. E. 2022. Leyes de

etiquetado frontal como garantía de protección a la salud de los consumidores.

Revista Universidad y Sociedad. 14(S3): 52-59.

2. Ayuso, A. 2023.

Acuerdos de asociación entre la UE y América Latina y el Caribe: algunas claves

para su actualización. CIDOB Briefings. N° 46: 1-6. https://www.cidob.org/es/

publicaciones/serie_de_publicacion/cidob_briefings/acuerdos_de_asociacion_entre_la_

ue_y_america_latina_y_el_caribe_algunas_claves_para_su_actualizacion.

[Consulta: 20 de agosto de 2023].

3. Campos, M. 2018.

Más normas, menos seguridad: el problema de la seguridad jurídica en todo

proceso de reforma. Vox Juris. Lima (Perú). 35(1): 117-125.

4. Cano, V. E.;

Castillo Quero, M.; De Haro Giménez, T. 2017. EU-MERCOSUR trade agreement:

finding winners products for Paraguay. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Mendoza. Argentina. 49(2): 289-302.

5. Centanaro, E.

2017. Análisis metodológico del Código Civil y Comercial de la Nación. Revista

Anales de la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales. UNLP. 14(47): 93-116.

6. de la Casa, L.;

López, L. B.; Rodríguez, V. G.; Dyner, L. M.; Greco, C. B. 2023. Logos,

símbolos y leyendas presentes en los rótulos de alimentos envasados: un

análisis crítico desde la legislación vigente en Argentina. Actualización en

Nutrición. 24(2): 103-110.

7. de la Puente y

Lavalle, M. 1994. La codificación. THEMIS: Revista de Derecho. N° 30: 29-36.

8. Diez-Picazo y

Ponce de León, L. 1993. Codificación, descodificación y recodificación. Anuario

de Derecho Civil. XLV(2): 473-484.

9. Espinosa Huerta,

A.; Luna Carrasco, J.; Morán Rey, F. J. 2015. Aplicación del etiquetado frontal

como medida de salud pública y fuente de información nutricional al consumidor:

una revisión. Revista Española de Nutrición Comunitaria. 21(2): 34-42.

10. FAO/OMS. 1985.

Codex Alimentarius. Norma general para el etiquetado de los alimentos

preenvasados CXS 1-1985.

https://www.fao.org/fao-whocodexalimentarius/codex-texts/ list-standards/es/.

[Consulta: 15 de setiembre de 2023].

11. García Ramírez,

J. 2012. A propósito del Código y la codificación. Precedente: Revista

jurídica. 1: 119-148.

12. Gorrín Peralta,

C. 1991. Fuentes y Procesos de Investigación Jurídica. Oxford NH: Equity

Publishing Co.

13. Guajardo, C. A.

1998. Código Alimentario Argentino. Su valoración jurídica. Mendoza: Ediciones

Jurídicas de Cuyo.

14. Guzmán Brito,

A. 1993. Codificación, descodificación y recodificación del derecho civil.

Revista de Derecho y Jurisprudencia y Gaceta de los Tribunales. 90(2): 39-62.

15. Hinestrosa

Forero, F. 2014. Codificación, descodificación y recodificación. Revista de

Derecho Privado. 27: 3-13.

16. Karavaski, N.; Curriá, M. 2020. La importancia de la

correcta interpretación del rotulado nutricional. Fronteras en Medicina. 15(1):

3135.

17. Mejorada Chauca,

M. 2011. Codificación civil y reforma. THEMIS: Revista de Derecho. 60: 13-18.

18. Negro, S. 2023.

El acceso y la comercialización de alimentos en mercados integrados: un puente

que une aspectos privados y públicos. Latin American Journal of European Studies.

3(1): 264-298.

19. Palomino

Araníbar, M. A. 2017. Derecho de Personas. Huancayo: Universidad Continental.

20. Risolía, M. A.

1957. La metodología del Código Civil en Materia de Contratos. Revista

Lecciones y Ensayos. Buenos Aires: UBA. 1957: 45-64.

21. Torres

Manrique, F. J. 2006. Codificación. Derecho y Cambio Social. Año 3. N° 7.

https://www. derechoycambiosocial.com/revista007/codificacion.htm. [Consulta:

20 de setiembre de 2023].

22. Vidal, F. 2000.

El Derecho Civil en sus conceptos fundamentales. Lima: Gaceta Jurídica.

23. World Health Organization. 2004. Global Strategy on Diet,

Physical Activity and Health. Resolution of the Fifty-seventh World Health

Assembly. WHA57.17. Geneva: World Health Organization. 15-21.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241592222. (Consulta: 24 de setiembre

de 2023).