Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

Impact

of Cry1Ac soybean (Glicine max) on biological and reproductive cycles

and herbivory capacity of Spodoptera

cosmioides and Spodoptera eridania

(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Impacto

de la soja (Glicine max) Cry1Ac sobre el ciclo biológico, reproductivo y

la capacidad herbívora de Spodoptera

cosmioides y Spodoptera eridania

(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Verónica Eugenia

Ruiz2,

María Cecilia Curis1,

Melina Soledad

Buttarelli3,

Pablo Daniel

Sánchez1,

Roberto Ricardo

Scotta1

1 Universidad Nacional del Litoral. Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Departamento de Producción Vegetal. Kreder 2805 (3080). Esperanza.

Santa Fe. Argentina.

2 Universidad Nacional del Litoral. Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. ICiAgro Litoral. CONICET, Esperanza. Argentina.

3 Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Rafaela (INTA E.E.A.

Rafaela). Área de producción Vegetal. Ruta 34 km 227 (2300). Rafaela. Santa Fe.

Argentina.

* alutz@fca.unl.edu.ar

Abstract

Increasing

populations of Spodoptera cosmioides (Walker) and Spodoptera eridania

(Stoll) have recently been detected in soybean crops in central Argentina.

Besides being polyphagous, these species tolerate the Cry1Ac insecticidal

toxin, expressed by genetically modified Bt soybean (MON89788 x

MON87701). Consequently, when facing big populations, farmers often apply

insecticides. This study aimed to determine the effects of Bt soybean on

the consumption, biological cycle, and reproduction of both Spodoptera species.

Larval feeding on Bt soybean led to a shorter pupal period (23% less

than control) and a decreased leaf-area consumption for S. cosmioides (14%

less than the non-Bt soybean). In S. eridania, the larval stage,

adult longevity, larva-to-adult, and oviposition periods were reduced (11, 23,

13, and 30% shorter than control, respectively). Despite these reductions, both

Lepidoptera species completed their reproductive cycles. These valuable findings

help us understand the biology of these potential pests in Bt soybean

crops in Argentina.

Keywords: Glicine max (L.), plant resistance, non-target pests, black armyworm, southern

armyworm

Resumen

En los últimos

años, las poblaciones de Spodoptera cosmioides (Walker) y Spodoptera

eridania (Stoll) se han incrementado en los cultivos de soja de la zona

central de Argentina. Además de ser polífagas, estas especies son tolerantes a

la toxina insecticida Cry1Ac expresada por la soja Bt genéticamente

modificada (MON89788 x MON87701), por lo que los agricultores deben recurrir al

control químico con insecticidas cuando se presentan altas densidades

poblacionales. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar el efecto de la soja Bt

sobre el consumo, ciclo biológico y reproducción de ambas especies de Spodoptera.

La alimentación larval con soja Bt determinó una menor duración del

período pupal (23% menos que el tratamiento control) y una disminución en el

consumo de área foliar en S. cosmioides (14% menos que la soja no Bt).

Spodoptera eridania registró una menor duración del estado larval,

longevidad de adultos, período larva-adulto y del período de oviposición (11,

23, 13 y 30% menos que el tratamiento control, respectivamente). Sin embargo,

ambas especies de Lepidoptera completaron su ciclo reproductivo con éxito. Los

resultados obtenidos en este trabajo son de gran utilidad para comprender la

biología de estas especies, que tienen el potencial de convertirse en plagas

importantes en los cultivos de soja Bt en Argentina.

Palabras clave: Glicine max (L.), plantas resistentes, plagas no blanco, oruga cogollera negra,

oruga cogollera del sur

Originales: Recepción: 15/02/2024- Aceptación: 18/10/2024

Introduction

Genetically

modified (GM) crops exhibiting insect-resistance are valuable tools in

integrated pest management (IPM) systems (25). These crops

express genes derived from the entomopathogenic bacterium Bacillus

thuringiensis Berliner (Bt), producing (Cry) proteins with highly

selective insecticidal activity. Bt soybean expressing these

insecticidal toxins is effective in controlling several major lepidopteran

pests in agricultural environments, including Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner),

Chrysodeixis includens (Walker), Helicoverpa gelotopoeon (Dyar)

and Rachiplusia nu (Guenée) (44).

High efficacy of Bt

soybean crops against pest populations and the consequent reduced insecticide

use has significantly altered the agroecosystem. Consequently, the reduced

interspecific competition after controlling Bt target species has

facilitated the emergence of new phytophagous pest species; many of which could

become economically significant (19, 30, 47). Recent reports

mention increasing populations of Spodoptera cosmioides Walker and Spodoptera

eridania Stoll (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Argentinean soybean crops,

including Bt cultivars (23, 29, 30, 32). Factors

contributing to these phenomena include tolerance to the Cry1Ac protein,

insecticide resistance and the ability to complete life cycles on the weed Amaranthus

sp. (2, 5, 9, 24, 26, 30). S. eridania thrives

in temperate regions like the Argentinean Pampas, with a developmental

threshold of 11.9°C and an inability to complete its life cycle above 34°C. In

contrast, S. cosmioides is adapted to warmer temperatures (from 13.2),

prevailing in soybean and cotton crops in northern Argentina (31). Although soybean

and cotton are the preferred hosts (11), caterpillars of

both species are polyphagous, and develop on weeds and grain, fruit, and

ornamental crops (14). These species

also have greater herbivorous potential than other soybean defoliators,

consuming vegetative structures, flowers, and pods (6,

21, 27, 38).

Understanding biological and reproductive pest cycles is

essential for elucidating population dynamics and predicting potential crop

populations. Most studies assessing the effects of the Cry1Ac protein on the

development and foliar consumption of lepidopteran pests (4,

5, 8, 12) have been conducted in Brazil, with almost no equivalent in

Argentina. This study hypothesized that the Cry1Ac protein affects biological

performance, reproduction, and feeding behavior of both Spodoptera species.

We investigated the impact of Bt soybean on foliar consumption and life

cycle to assess pest potential in the central soybean region of Argentina.

Materials

and methods

This study was

conducted in the breeding chamber of the Plant Production Department at the

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias (Universidad Nacional del Litoral), in Esperanza

City, Santa Fe province, Argentina.

Insect

rearing

Spodoptera

cosmioides and S. eridania larvae were collected in February 2019

from commercial soybean fields in Santa Fe province, near Franck (31°35’00” S

60°56’00” W, 31 m a. s. l.) and Santa María Norte (31°31’00” S 61°08’00” W, 44

m a. s. l.). The caterpillars were transported to the breeding chamber in

containers with soybean leaves and identified using taxonomic keys (43,

46). They were reared under controlled temperature (24 ± 2°C),

relative humidity (60%), and photoperiod (14:10 h, light: dark) in transparent

PVC boxes (26 cm long, 17 cm wide, and 7 cm high), covered with muslin caps for

air circulation. An artificial diet consisting of corn flour, wheatgerm, yeast,

water, agar, nipagin, benzoic acid, and ascorbic acid was provided until pupation

(33). The emerged

adults were placed in oviposition cages (50 cm length, 40 cm width, and 40 cm

height), with paper sheets for oviposition. They were fed daily with an

artificial adult diet (10) provided through

soaked cotton. Eggs were collected daily and placed in 9 cm diameter Petri

dishes with artificial feed for neonate larvae. Three days after hatching,

larvae were transferred to PVC boxes for large-scale rearing with an artificial

diet. This process continued until the F2 generation, ensuring enough

population for the study.

Plant

material

Leaves for larvae

feed were obtained from soybean cultivars RA 5715 IPRO (Bt) and RA 549

(non-Bt). Both cultivars are glyphosate-tolerant, but only the former

expresses the Cry1Ac toxin. To ensure a continuous supply of leaves, both

cultivars were periodically planted in 3x2 m plots under field conditions.

Weeds were manually removed and soybean plants were kept disease-free by the

eventual application of fungicides.

Effect

of Bt soybean on the biological and reproductive cycle of S.

cosmioides and S. eridania

A second instar

(L2) larva of either S. cosmioides or S. eridania was placed on

two soybean leaflets (from Bt or non-Bt soybean plants, depending

on the treatment) inside 9 cm diameter Petri dishes lined with absorbent paper.

Petioles were wrapped in cotton saturated with distilled water, maintaining

humidity. Bt and non-Bt soybean leaflets were harvested at V6-V8

vegetative stage before anthesis, according to phenology by Fehr et

al. (1977). The V6-V8 vegetative stage corresponds to maximum Cry1Ac

expression in the Bt cultivar (45). Food and

absorbent papers were renewed daily until pupation. We defined sex by observing

the terminal portion of pupae (7) using a

stereomicroscope set (Lancet Instruments, China) at 30× magnification. Thirty

replicates were performed for each treatment (Bt and non-Bt soybean)

and species (S. cosmioides and S. eridania). Once adults emerged,

one couple was placed per oviposition container (17 cm height, 11 cm upper

diameter, and 7 cm lower diameter), covered with a muslin cap facilitating air

circulation and preventing adult escape. The same diet used for rearing was

supplied to adults with soaked cotton (10). Fecundity was

determined by daily collecting egg masses laid by females after mating. Egg

masses were photographed using an Olympus SZ40 stereomicroscope (Olympus

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 40X for egg counting, considering any overlapping

or superimposed eggs. Each egg mass was placed in a separate Petri dish (9 cm

diameter) lined with absorbent paper and food for emerging neonates. Fertility

(viable eggs) was estimated by the number of viable larvae hatched from each

egg mass. The assays were conducted with 11 and 10 couples of S. cosmioides and

14 and 10 couples of S. eridania for the Bt and non-Bt soybean

treatments, respectively.

The following variables were recorded: duration (in days) of

larval, pupal and adult stages, the larva-to-adult period, pupal weight (g)

using an OHAUS-PIONNER precision scale (± 0.0001 g), fecundity (number of

eggs/female), fertility (number of hatched eggs), pre-oviposition (days from

adult emergence to first egg laying), oviposition (days from the first to the

last egg laying), and post-oviposition (days from last egg laying to death).

Effect of Bt soybean on leaf consumption by larvae of S.

cosmioides and S. eridania

Leaf

area consumption (cm2) was determined using the same larvae and

soybean cultivars (species and treatments) as when assessing the impact of Bt

soybean on the biological and reproductive cycle. Fresh leaflets were

provided daily as food, and the remaining unconsumed portions were scanned

using an HP Deskjet F4280 multifunction printer. The consumed leaf area was

quantified by image analysis with ImageJ® software (1).

Adjusted leaf area loss due to dehydration was based on data from soybean

leaflets not exposed to larvae.

Statistical analysis

Bioassays

for each lepidopteran species were conducted independently under a completely

randomized experimental design. Since the duration of larva, pupal, and adult

stages, as well as the larva-to-adult period did not meet normality,

non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (α ≤ 0.05) was performed. Pupal weight was

analyzed by ANOVA and Tukey test (α ≤ 0.05). Foliar consumption

means were compared using an independent

samples T-test (α ≤ 0.05). All statistical analyses were conducted using

InfoStat software (13).

Results

Effect of Bt soybean on the biological and reproductive

cycle of S. cosmioides and S. eridania

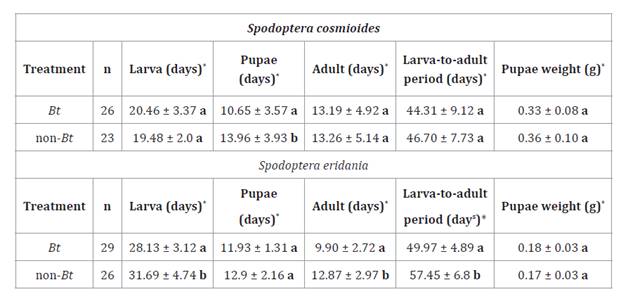

Feeding

S. cosmioides larvae with Bt soybean leaves did not significantly

affect larval duration compared to control, with 20.46 and 19.48 days,

respectively (H= 0.64; p= 0.4160) (table 1).

However, in S. eridania, significant differences were evidenced for

larval length of 28.13 days when fed with Bt soybean leaves and 31.69

days when supplied with non-Bt soybean leaves (H= 7.43; p= 0.0062) (table

1).

Significant differences in the S. cosmioides pupal stage

duration showed 10.65 and 13.96 days (H= 14.72; p= 0.0001), with Bt and

non-Bt soybean, respectively. In S. eridania, differences were

not significant (H= 3.77; p= 0.0434) (table 1). Regarding the adult stage, no

significant differences were found in S. cosmioides (H= 0.04; p=

0.8485). However, S. eridania adults lived significantly longer on non-Bt

soybean leaves (12.87 days), compared to Bt soybean (9.90 days) (H=

11.70; p= 0.0005) (table

1).

Table

1. Days of larval, pupal, and adult stages,

larva-to-adult period, and pupae weight (g) (Mean ± SD) of Spodoptera

cosmioides and S. eridania, fed Bt and non-Bt soybean

leaves under controlled conditions.

Tabla

1. Duración (días) de los estadios

larval, pupal y adulto, el período de larva a adulto y el peso de las pupas (g)

(Media ± DE) de Spodoptera cosmioides y S. eridania, alimentadas

con hojas de soja Bt y no-Bt en condiciones controladas.

*

Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. (Test:

Kruskal Wallis, α ≤ 0.05). Pupal weight (Test: Tukey, α ≤ 0.05).

*Diferentes letras en las columnas

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos (Prueba: Kruskal Wallis,

α ≤ 0,05). Peso de pupa (Prueba: Tukey, α ≤ 0,05).

The

larva-to-adult period for S. cosmioides was 44.31 days on Bt soybean

and 46.70 days on non-Bt soybean, with no significant differences (H=

0.48; p= 0.4881). In contrast, S. eridania had a larva-to-adult period

significantly longer on non-Bt soybean (57.45 days) compared to Bt soybean

(49.97 days) (H= 13.89; p= 0.0002) (table 1).

Considering

pupal weight, no significant differences were found for either species: S.

cosmioides (F= 0.95; p= 0.3359) and S. eridania (F= 3.77; p= 0.0577)

(table

1).

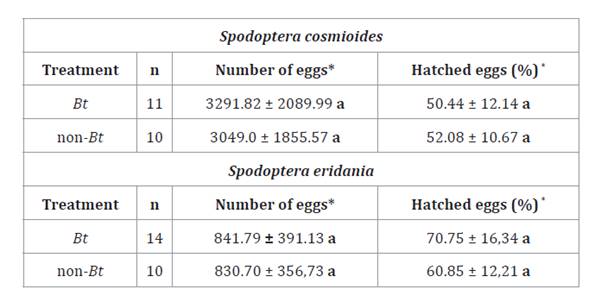

Larval

feeding did not affect average number of eggs per female in either species. S.

cosmioides had 3291.82 eggs on Bt soybean leaves and 3049.0 on non-Bt

soybean leaves (H= 0.08; p= 0.7782). S. eridania had lower fecundity

than S. cosmioides, with 841.79 eggs on Bt soybean and 830.70

eggs on non-Bt soybean (H= 0.01; p= 0.9068) (table 2).

The Cry1Ac protein ingested by larvae did not affect fecundity in the studied

species (table

2). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in

fertility (percentage of hatched eggs) between treatment species (H= 0.04; p=

0.8327 for S. cosmioides and H= 2.14; p= 0.1432 for S. eridania)

(table

2).

Table

2. Fecundity (number of eggs) and Fertility

(% of hatched eggs) (Mean ± SD) of Spodoptera cosmioides and S. eridania

fed Bt and non-Bt soybean leaves under controlled conditions.

Tabla

2. Fecundidad (número de huevos) y

fertilidad (% de huevos eclosionados) (Media ± DE) de Spodoptera cosmioides y

S. eridania alimentadas con hojas de soja Bt y no-Bt en

condiciones controladas.

*Different

letters in columns indicate significant differences between treatments. (Test:

Kruskal Wallis α ≤ 0.05).

* Diferentes letras en las columnas

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos (Prueba: Kruskal Wallis α

≤ 0,05).

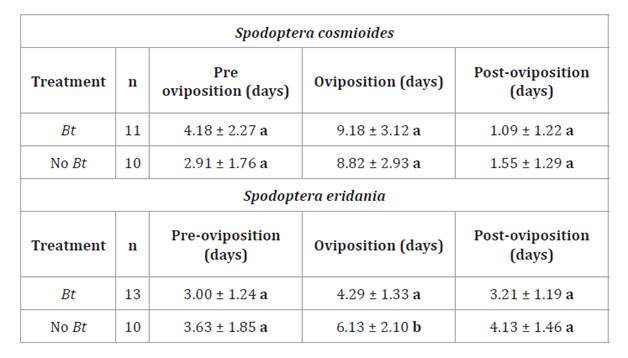

Pre

and post-oviposition periods were similar for both species under both larval

feeding treatments (table 3),

(H= 1.32; p= 0.2395 and H= 0.85; p= 0.34 for S. cosmioides, respectively;

H= 0.51; p= 0.4460 and H= 2.25; p= 0.1238 for S. eridania,

respectively). However, significant differences were found in the oviposition

period for S. eridania, with 4.29 and 6.13 days in adults emerging from

larvae fed Bt and non-Bt soybean leaves, respectively (H= 4.62;

p= 0.0293).

Table 3. Pre-oviposition,

oviposition and post-oviposition periods of Spodoptera cosmioides and S.

eridania (Mean ± SD) fed Bt and non-Bt soybean leaves under

controlled conditions.

Tabla 3. Períodos

de preoviposición, oviposición y postoviposición de Spodoptera cosmioides y

S. eridania (Media ± DE) alimentados con hojas de soja Bt y no Bt

en condiciones controladas.

* Different letters in columns

indicate significant differences between treatments. (Test: Kruskal Wallis α ≤

0.05).

*

Diferentes letras en las columnas indican diferencias significativas entre

tratamientos (Prueba: Kruskal Wallis α ≤ 0,05).

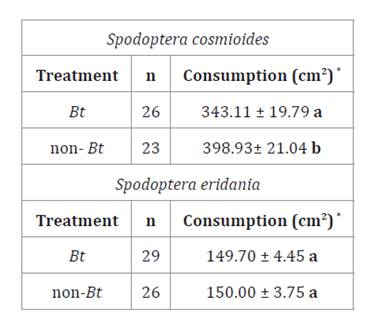

Effect of Bt soybean on leaf consumption by S.

cosmioides and S. eridania

Total leaf area consumption by S. cosmioides was lower

when larvae were fed with Bt soybean (T= -2.77; p= 0.0081). In contrast,

S. eridania showed no significant differences in leaf area consumption

between Bt and non-Bt soybean leaves (T= 0.05; p= 0.9585) (table 4).

Table

4. Leaf area consumption of Spodoptera

cosmioides and S. eridania (Mean ± SD) fed Bt and non-Bt soybean

leaves under controlled conditions.

Tabla

4. Consumo de área foliar de Spodoptera

cosmioides y S. eridania (Media ± DE) alimentados con hojas de soja Bt

y no Bt en condiciones controladas.

*Different

letters in columns indicate significant differences between treatments. (Test:

T, α ≤ 0.05).

* Diferentes letras en las columnas

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos. (Test: T, α ≤ 0,05).

Discussion

gM crops expressing

Cry proteins are crucial for pest control. Besides killing susceptible species,

these crops can have sublethal effects on tolerant species, through direct or

indirect exposure, leading to broader ecological changes (40). Spodoptera

cosmioides and S. eridania exhibit tolerance against the Cry1Ac

protein (2) due to the type

and quantity of receptor proteins in larval midgut membranes, low receptor

affinity, or rapid protein degradation (35). Thus, insect

exposure to stress factors like Cry1Ac protein expressed by Bt soybean

may enhance fitness of the exposed population (17,

18). This explains why S. eridania individuals exhibited

shorter durations in both larval and adult stages, and a reduced larva-to-adult

period when fed soybean leaves expressing the Cry1Ac protein. In contrast, S.

cosmioides only experienced a decrease in the pupal period when fed on

insect-resistant GM soybeans (Bt).

Regarding

larval cycle, our results for S. cosmioides agree with Bernardi

et al. (2014) and Silva et al. (2019),

who observed a similar duration for the last larval stage under the same

treatments. In contrast, S. eridania showed significant differences

between treatments with an average duration of 28.13 days on Bt soybeans

and 31.69 days on non-Bt soybeans. These results are consistent with

those reported by Bortolotto et al. (2014)

and Rabelo et al. (2020),

who observed a significant reduction of 2 days in the larval stage of S.

eridania when fed GM soybeans expressing Cry1Ac.

Our

results showed that S. eridania adults from Bt soybeans live 3

days less than those from the control group. In contrast, Silva

(2013) and Bortolotto et al. (2014)

reported a significant 3 days-increase in longevity of S. eridania males

when reared on Bt soybean leaves. This discrepancy suggests that Cry1Ac

might induce asynchronous adults’ emergence between the two cultivars,

potentially reducing mating chances in natural conditions. According to Jakka

et al. (2014) and Murúa et al. (2019),

the non-simultaneous emergence of adults in both cultivars could compromise the

refuge strategy to avoid or delay resistance emergence. On the other hand, we

found a shortened life cycle of S. eridania (7.48 days) when larvae were

fed soybeans expressing Cry1Ac, as seen by Ramírez &

Gómez (2010), who reported an average life cycle of 51.72 days for S.

eridania with artificial diet.

Several

studies have demonstrated that noctuid pupae weight can vary with temperature,

host plants, and exposure to sublethal insecticide concentrations or Bt crop

toxins (22).

However, our results indicate that Bt protein did not affect pupal

weight of either species. Additionally, feeding larvae with Bt soybean

leaves did not affect the reproductive capacity of either Spodoptera species,

as observed by Silva et al. (2016)

and Sosa et al. (2020),

in S. cosmioides for larvae fed with Bt soybean leaves. However, Páez

Jerez et al. (2022) reported more eggs per female in S.

cosmioides individuals fed Bt soybean. According to Specht

& Roque-Specht (2019), fecundity in S. cosmioides is

highly variable, with females capable of producing up to 5000 eggs/female,

higher than for S. eridania, S. albula, S. frugiperda and S.

littoralis (26, 27).

In our study, average egg number per S. eridania female is consistent

with Silva (2013), who reported similar

fecundity in females reared on both Bt and non-Bt soybeans during

larval stage, with averages of 881.35 and 911.85 eggs per female, respectively.

We

found that exposure to the insecticidal protein Cry1Ac during larval stage

shortened the oviposition period in S. eridania. Although the literature

lacks specific data on the oviposition period of S. eridania fed on Bt

cultivars, previous studies have reported variable oviposition periods

ranging from 4.2 days to 6. 75 days when larvae were reared on non-Bt soybean

leaves (14).

Biological

fitness is the ability of an organism to compete successfully, pass on its

genes to subsequent generations and influence population density and the

potential to become a pest. However, insecticide exposure can have variable

effects, enhancing or reducing performance, potentially leading to adverse

impacts on survival, developmental rate, reproduction, and adult longevity (3).

This phenomenon has been documented in several Lepidoptera species exposed to Bt

protein (16).

In our study, we observed a reduced pupal period in S. cosmioides and

shortened larval, adult, and larval-to-adult cycles and oviposition periods in S.

eridania when fed Bt soybean leaves.

Food quantity and quality directly influence host plant

preference affecting biological, physiological, and behavioral features (11). While some

studies have found no effects of Cry toxins on foliar consumption in

lepidopterans (11), other research

reports less leaf consumption due to Cry proteins in corn (5), as we found for S.

cosmioides. According to Zurbrügg et al. (2010),

glyphosate-resistant soybeans expressing the Cry1Ac toxin have more

carbohydrates and lower protein content than non-transgenic cultivars. This

variation in nutritional composition may influence insect food preference as

seen in S. cosmioides when fed on Cry1Ac-expressing soybean.

Conclusion

Transgenic crops expressing Cry insecticidal proteins are

valuable tools for controlling susceptible pests. However, they may also induce

changes in life cycles, population dynamics, reproductive stages, feeding behavior,

or longevity of non-target species. Understanding developmental and

reproductive parameters of these non-target pests is essential for predicting

population growth and species dynamics within agricultural systems. Our

findings shed light on the biology of S. cosmioides and S. eridania in

Bt soybean crops in Argentina, considering foliar consumption and

herbivorous capacity. Since our experiments were conducted under controlled

conditions, these investigations should further assess actual field damage

caused by Spodoptera species in soybean crops.

1.

Abràmoff, M. D., Magalhães, P. J.; Ram, S. J. 2004. Image processing with

ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 11(7): 36-42.

2.

Bernardi, O.; Sorgatto, R. J.; Barbosa, A. D.; Domínguez, F. A.; Dourado, P.

M.; Carvalho, R. A.; Martinelli, S.; Head, G. P.; Omoto, C. 2014. Low

susceptibility of Spodoptera cosmioides, Spodoptera eridania and Spodoptera

frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to genetically-modified soybean

expressing Cry1Ac protein. Crop Protection. 58: 33-40. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.cropro.2014.01.001

3.

Bird, L. J.; Akhurst, R. J. 2004. Relative fitness of Cry1A-resistant and

-susceptible Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on

conventional and transgenic cotton. Journal of Economic Entomology. 97:

1699-1709. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493- 97.5.1699

4.

Bortolotto, O.; Silva, G. V.; De Freitas Bueno, A.; Pomari, A. F.; Martinelli,

S.; Head, G. P.; Carvahlo, R. A.; Barbosa, G. C. 2014. Development and

reproduction of Spodoptera eridania (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and its egg

parasitoid Telenomus remus (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) on the

genetically modified soybean (Bt) MON 87701×MON 89788. Bulletin of Entomological

Research. 104(6): 724-730. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485314000546

5.

Bortolotto, O. C.; de Freitas Bueno, A.; de Queiroz, A. P.; Vieira Silva, G.;

Caselato Barbosa, G. 2015. Larval development of Spodoptera eridania (Cramer)

fed on leaves of Bt maize expressing Cry1F and Cry1F + Cry1A.105 + Cry2Ab2

proteins and its Non-Bt isoline. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 59(3):7-11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbe.2014.12.001

6.

Bueno, R. C. O. F.; Bueno, A. F.; Moscardi, F.; Parra, J. R. P.; Hoffmann-Campo,

C. B. 2011. Lepidopteran larva consumption of soybean foliage: basis for

developing multiple-species economic thresholds for pest management decisions.

Pest Management Science. 67: 170-174. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2047

7.

Butt, B.; Cantu, E. 1962. Sex determination of lepidopterous pupae. Washington.

D.C: US Department of Agriculture. 33 p.

8.

Carpane, P. D.; Llebaria, M.; Nascimento, A. F.; Vivan, L. 2022. Feeding injury

of major lepidopteran soybean pests in South America. Plos one. 17(12).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0271084

9.

Coradin, J.; Braga Pereira Braz, G.; Guerra da Silva, A.; de Oliveira Procópio,

S.; Sales Vian, G.; Leão Lima Chavaglia, P. V.; Rodrigues Goulart, M. A.; de

Freitas Souza. 2023. Selectivity of latifolicides associated with glyphosate

applied in postemergence on soybean (Glycine max) cultivars. Revista de

la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 55(1): 86-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.098

10.

Curis, M. C.; Bertolaccini, I.; Lutz, A. 2017. Efecto de dietas en adultos de Spodoptera

cosmioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) sobre la fertilidad, fecundidad y

longevidad del adulto. Revista FAVE–Ciencias Agrarias. 16(2): 17-24.

10.14409/fa.v16i2.7015

11.

da Silva, D. M.; de Freitas Bueno, A.; dos Santos Stecca, C.; Andrade, K.;

Neves, P. M. O. J.; de Oliveira, M. C. N. 2017. Biology of Spodoptera

eridania and Spodoptera cosmioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on

different host plants. Florida Entomologist. 100(4): 752-760. https://doi.

org/10.1653/024.100.0423

12.

de Sousa Ramalho, F.; Azeredo, T. L.; Bezerra de Nascimento, A. R.; Sales

Fernandes, F.; Nascimento Júnior, J. L.; Malaquias, J. B.; da Vieira Silva, C.

A. D.; Cola Zanuncio, J. 2011. Feeding of fall armyworm, Spodoptera

frugiperda, on Bt transgenic cotton and its isoline. Entomologia

Experimentalis et Applicata. 139(3): 207-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1570-

7458.2011.01121.x

13.

Di Rienzo, J. A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.;

Robledo, C. W. 2014. InfoStat versión 2014. Córdoba, Argentina: Grupo InfoStat.

Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Argentina.

http://www.infostat.com.ar

14. Dos Santos, K. B.; Meneguim, A. M.; Neves, P. M. O. J. 2005.

Biologia de Spodoptera eridania (Cramer) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) em

diferentes hospedeiros. Neotropical Entomology. 34: 903-910.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2005000600005

15.

Fehr, W. R.; Caviness, C. E.; Burmood, D. T.; Pennington, J. S. 1971. Stage of

development descriptions for soybeans, Glycine Max (L.) Merrill 1. Crop

Science. 11(6): 929-931. https://doi.

org/10.2135/cropsci1971.0011183X001100060051x

16.

Gassmann, A. J.; Carrière, Y.; Tabashnik, B. E. 2009. Fitness costs of insect

resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Annual Review of Entomology.

54(1): 147-163. 10.1146/annurev. ento.54.110807.090518

17.

Guedes, R. N. C.; Cutler, G. C. 2014. Insecticide-induced hormesis and

arthropod pest management. Pest Management Science. 70: 690- 697.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.3669

18.

Guedes, R. N. C.; Walse, S. S.; Throne, J. E. 2017. Sublethal exposure,

insecticide resistance, and community stress. Current Opinion in Insect Science.

21: 47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cois.2017.04.010

19.

Horikoshi, R. J.; Dourado, P. M.; Berger, G. U.; de S. Fernandes, D.; Omoto,

C.; Willse, A.; Martinelli, S.; Head, G. P.; Corrêa, A. S. 2021. Large-scale

assessment of lepidopteran soybean pests and efficacy of Cry1Ac soybean in

Brazil. Scientific Reports. 11(1): 15956.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95483-9

20.

Jakka, S. R. K.; Knight, V. R.; Jurat-Fuentes, J. L. 2014. Fitness costs

associated with field-evolved resistance to Bt maize in Spodoptera

frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of Economic Entomology.

107(1): 342-351. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13326

21.

Justus, C. M.; Paula-Moraes, S. V.; Pasini, A.; Hoback, W. W.; Hayashida, R.;

de Freitas Bueno, A. 2022. Simulated soybean pod and flower injuries and

economic thresholds for Spodoptera eridania (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

management decisions. Crop Protection. 155: 105936. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2022.105936

22.

Liu, Z.; Gong, P.; Li, D.; Wei, W. 2010. Pupal diapause of Helicoverpa

armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) mediated by larval host plants:

pupal weight is important. Journal of Insect Physiology. 56: 1863-1870.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.08.007

23.

Lutz, A. L.; Bertolaccini, I.; Scotta, R. R.; Mantica, F.; Magliano, M. F.;

Sanchez, P. D.; Curis, M. C. 2019. Primer reporte de Spodoptera eridania (Stoll)

(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) en el Centro de la Provincia de Santa Fe. Revista FAVE

- Ciencias Agrarias. 18(2): 7-12. https://doi. org/10.14409/fa.v19i2.8781

24.

Machado, E. P.; dos S Rodrigues Junior, G. L.; Somavilla, J. C.; Führ, F. M.;

Zago, S. L.; Marques, L. H.; Santos, A. C.; Nowatzki, T.; Dahmer, M. L.; Omoto,

C.; Bernardi, O. 2020. Survival and development of Spodoptera eridania, Spodoptera

cosmioides and Spodoptera albula (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on

genetically‐modified soybean expressing Cry1Ac and Cry1F proteins. Pest

Management Science. 76 (12): 4029-4035. https://doi. org/10.1002/ps.5955

25.

Martins-Salles, S.; Machado, V.; Massochin-Pinto, L.; Fiuza, L. M. 2017.

Genetically modified soybean expressing insecticidal protein (Cry1Ac):

Management risk and perspectives. Facets. 2: 496-512.

https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2017-0006

26.

Montezano, D. G.; Specht, A.; Sosa-Gómez, D. R.; Roque-Specht, V. F.; de

Barros, N. M. 2014a. Immature stages of Spodoptera eridania (Lepidoptera:

Noctuidae): developmental parameters and host plants. Journal of Insect

Science. 14: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieu100

27.

Montezano, D. G.; Specht, A.; Sosa-Gómez, D. R.; Roque-Specht, V. F.; Bortolin,

T. M.; Fronza, E.; Pezzi, P. P.; Luz, P. C.; Barros, N. M. 2014b. Biotic

potential, fertility and life table of Spodoptera albula (Walker)

(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), under controlled conditions. Anais da Academia

Brasileira de Ciências. 86(2): 723-732. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0001-

3765201402812

28.

Murúa, M. G.; Vera, M. T.; Michel, A.; Casmuz, A. S.; Fatoretto, J.;

Gastaminza, G. 2019. Performance of field-collected Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera:

Noctuidae) strains exposed to different transgenic and refuge maize hybrids in

Argentina. Journal of Insect Science. 19 (6) 21: 1-7.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iez110

29.

Paez Jerez, P. G.; Hill, J. G.; Pereira, E. J.; Medina Pereyra, P.; Vera, M. T.

2022. The role of genetically engineered soybean and Amaranthus weeds on

biological and reproductive parameters of Spodoptera cosmioides (Lepidoptera:

Noctuidae). Pest Management Science. 78(6): 2502-2511. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6882

30.

Páez Jerez, G. P.; Hill, J. G.; Pereira, E. J.; Alzogaray, R. A.; Vera, M. T.

2023. Ten years of Cry1Ac Bt soybean use in Argentina: Historical shifts in the

community of target and non-target pest insects. Crop Protection. 170: 106265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2023.106265

31.

Parra, J. R. P.; Coelho, A.; Cuervo-Rugno, J. B.; Garcia, A. G.; de Andrade

Moral, R.; Specht, A.; Neto, D. D. 2022. Important pest species of the Spodoptera

complex: Biology, thermal requirements and ecological zoning. Journal of

Pest Science. 95(1): 169-186. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10340-021-01365-4

32.

Perotti, E.; Boero, L.; Gamundi, J. 2016. Manejo del complejo de plagas de

soja: MIP versus Control Preventivo. En: Para Mejor la Producción 54.

INTA-EEA Oliveros. Santa Fe. Argentina. 169-176.

33. Poitout, S.; Bues, R. 1974. Elevage de chenilles de

veingt-huit espeses de lépidopterés Noctuidae. Annales de Zoologie Ecologie

Animale. 6: 341-411.

34.

Rabelo, M. M.; Matos, J. M. L.; Santos-Amaya, O. F.; França, J. C.; Gonçalves,

J.; Paula-Moraes, S. V.; Guedes, R. N. C.; Pereira, E. J. G. 2020. Bt-toxin

susceptibility and hormesis-like response in the invasive southern armyworm (Spodoptera

eridania). Crop Protection. 132: 105129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105129

35.

Rahman, K.; Abdullah, M. A. F.; Ambati, S.; Taylor, M. D.; Adang, M. J. 2012.

Differential protection of Cry1Fa toxin against Spodoptera frugiperda larval

gut proteases by cadherin orthologs correlates with increased synergism. Applied

and Environmental Microbiology. 78: 354- 362.

https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.06212-11

36.

Ramírez, M.; Gómez, V. 2010. Biología de Spodoptera eridania (Cramer,

1782) (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae) en dieta natural y artificial, en condiciones de

laboratorio. Investigación Agraria. 12(1): 17-21.

37.

Silva, G. V. 2013. Efeito de plantas Bt de soja e milho sobre pragas não-alvo e

seus inimigos naturais. Dissertação. Mestrado em Ciências Biológicas.

Universidade Federal do Paraná. Curitiba.

38.

Silva, G.; de Freitas Bueno, A.; Bortolotto, O. C.; dos Santos, A. C.;

Pomari-Fernandes, P. 2016. Biological characteristics of black armyworm Spodoptera

cosmioides on genetically modified soybean and corn crops that express

insecticide Cry proteins. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 60: 255-259.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbe.2016.04.005

39.

Silva, A.; Baronio, C. A.; Galzer, E. C. W.; Garcia, M. S.; Botton, M. 2019.

Development and reproduction of Spodoptera eridania on natural hosts and

artificial diet. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 79(1): 80-86.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.177219

40.

Snow, A. A.; Andow, D. A.; Gepts, P.; Hallerman, E. M.; Power, A.; Tiedje, J.

M.; Wolfenbarger, L. 2005. Genetically engineered organisms and the

environment: current status and recommendations. Ecological Application. 15:

377-404. https://doi. org/10.1890/04- 0539

41.

Sosa, C.; Gómez, V.; Ramírez, M.; Gaona, E.; Gamarra, M. 2020. Toxicity of the Bt

Protein Cry1Ac expressed in leaves of the event of transgenic soybean

released in Paraguay against Spodoptera cosmioides. Journal of

Agricultural Science. 12(12): 107. https://doi. org/10.5539/jas.v12n12p107

42.

Specht, A.; Roque-Specht, V. F. 2019. Biotic potential and reproductive parameters

of Spodoptera cosmioides (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the

laboratory. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 79(3): 488-494.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.184595

43.

Teodoro, A. V.; Procopio, S. D. O.; Bueno, A. D. F.; Negrisoli Junior, A. S.;

de Carvalho, H. W. L.; Negrisoli, C. D. C.; Brito, L. F.; Guzzo, E. C. 2013. Spodoptera

cosmioides (Walker) e Spodoptera eridania (Cramer) (Lepidoptera:

Noctuidae): novas pragas de cultivos da Região Nordeste. Circular Técnica 131.

EMBRAPA. Brasília. DF.

44.

Vera, M. A.; Casmuz, A. S.; Murúa, M. G.; Fadda, L.; Gastaminza, G. A. 2019.

Plagas blanco de la soja Bt: Complejo de especies defoliadoras Lepidoptera:

Noctuidae. Avance Agroindustrial; 40(3): 28-29.

https://www.eeaoc.gob.ar/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/403-08Ficha-tecnica.pdf

45.

Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Romeis, J.; Wu, K. 2013. Expression of Cry1Ac in

transgenic Bt soybean lines and their efficiency in controlling lepidopteran

pests. Pest Management Science. 69(12): 1326-1333. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.3508

46.

Zenker, M. M.; Specht, A.; Corseuil, E. 2007. Estágios imaturos de Spodoptera

cosmioides (Walker) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Revista Brasileira de

Zoologia. 24: 99-107. https://doi. org/10.1590/S0101-81752007000100013

47.

Zhao, J. H.; Ho, P.; Azadi, H. 2011. Benefits of Bt cotton counterbalanced by

secondary pests? Perceptions of ecological change in China. Environmental

Monitoring and Assessment, 173: 985-994.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-010-1439-y

48.

Zurbrügg, C.; Hönemann, L.; Meissle, M.; Romeis, J.; Nentwig, W. 2010.

Decomposition dynamics and structural plant components of genetically modified

Bt maize leaves do not differ from leaves of conventional hybrids. Transgenic

Research. 19: 257-267. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11248-009-9304-x

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by the Universidad

Nacional del Litoral (Argentina), through the Curso de Acción para la

Investigación y Desarrollo (CAI + D) Program (50120150100131LI).