Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

Antimicrobial

and antioxidant properties of the woody endocarp of native and commercial

walnuts from Argentina

Propiedades

antimicrobianas y antioxidantes del endocarpio leñoso de nogales nativos y

comerciales de Argentina

Ingrid Georgina

Orce1,

Gabriela Inés

Furque2,

Emilia Lorenzo3,

Gretel Rodriguez

Garay4,

Fiamma Pereyra3,

María Rosa Alberto5,

Patricia Elizabeth

Gomez Kamenopolsky1, 3,

1 Centro Regional de Energía y Ambiente para el Desarrollo

Sostenible. CREAS (UNCA-CONICET) Prado 366. San Fernando del Valle de

Catamarca. CP K4700AAP. Catamarca. Argentina.

2 Universidad Nacional de Catamarca. Facultad de Ciencias Exactas

y Naturales. Departamento de Química. Av. Belgrano al 300. San Fernando del

Valle de Catamarca. CP K4700AAP. Catamarca. Argentina.

3 Universidad Nacional de Catamarca. Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Departamento de Química. Av. Maestro Quiroga 50. San Fernando del

Valle de Catamarca. CP K4700AAP. Catamarca. Argentina.

4 Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA). Estación

Experimental Agropecuaria Catamarca. Ruta 33 km 4.5 (4705). Valle Viejo.

Catamarca. Argentina.

5 Instituto de Biotecnología Farmaceútica y alimentaria

(INBIOFAL) Predio Universitario Ingeniero Herrera. Av. Kirchner 1900. CP 4000.

San Miguel de Tucumán. Tucumán. Argentina.

*

mario.arena@fbqf.unt.edu.ar

Abstract

Juglans australis is a tree from the Juglandaceae

family found in the southernmost region of America. Its small edible nuts

are not commercialized, and their bioactive characteristics are unknown. This

study first reports the antioxidant, antiradical, and antibacterial activity of

extracts from this native walnut against phytopathogenic bacteria and compared

with its commercial counterpart, J. regia L. Different extracts from the

woody endocarp (shells) were obtained using methanol and ethyl acetate.

Methanolic extracts significantly inhibited phytopathogenic growth at all

concentrations tested (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/mL). The best activity was reported

against Xanthomonas. Highest total phenolics and the most significant

antioxidant activity were determined in methanolic extracts (TPC: 121 mg gallic

acid equivalent (GAE)/g of dried peel, FRAP: 58.6 mmol Trolox/100 g of peel

dried and 9.7 mM Trolox/100 g of dried peel). Extracts from both species

demonstrated congruent patterns. Gallic acid was the most abundant compound in

the methanolic extract. However, extracts demonstrated superior efficiency,

suggesting a potential synergistic effect among their components. Antioxidant

and antimicrobial activity of methanolic extracts against Xanthomonas make

them potential control agents.

Keywords: Juglans australis, phytopathogens,

polyphenols, bioactive compounds, sustainable agriculture, Xanthomonas sp.

Resumen

Juglans australis es un árbol

perteneciente a la familia Juglandaceae que se encuentra en la región

más austral del continente americano. Aunque las nueces también son

comestibles, son pequeñas y no se comercializan, sus características bioactivas

son desconocidas. Este estudio constituye el primer informe sobre la actividad

antioxidante, antirradical y antibacteriana de extractos de la nuez nativa

frente a bacterias fitopatógenas, y su comparación con la especie comercial, J.

regia L. Se obtuvieron diferentes extractos a partir del endocarpio leñoso

(cáscaras) utilizando metanol y acetato de etilo. El extracto metanólico

resultó ser la fracción más activa e inhibió significativamente el crecimiento

de los fitopatógenos en todas las concentraciones analizadas (0,1, 1 y 10

mg/mL). La mejor actividad se registró para el género Xanthomonas. El

mayor contenido de fenoles totales y la actividad antioxidante más significativa

se determinó en el extracto metanólico (TPC: 121 mg de ácido gálico equivalente

(GAE)/g de cáscara seca, FRAP: 58,6 mmol de Trolox/100 g de cáscara seca y 9,7

mM de Trolox/100 g de cáscara seca). Los extractos de ambas especies se

comportaron de manera similar. Al analizar la composición química, el ácido

gálico fue el compuesto más abundante en el extracto metanólico. Sin embargo,

los extractos mostraron una eficiencia superior, lo que sugiere un posible

efecto sinérgico entre sus componentes. La actividad antimicrobiana de los

extractos metanólicos contra Xanthomonas, junto con su capacidad

antioxidante, resalta su potencial aplicación como agentes de control de

fitopatógenos.

Palabras claves: Juglans australis, fitopatógenos,

polifenoles, compuestos bioactivos, agricultura sustentable, Xanthomonas sp.

Originales: Recepción: 23/06/2023 - Aceptación: 05/12/2024

Introduction

Phytopathogens

cause significant economic loss in agriculture (35). Even considering

synthetic pesticides imply detrimental environmental and human health

consequences, several products are still being used. In the last decade,

eco-friendly compounds have emerged as alternative pesticides (8,

19). These natural antimicrobial agents are safer and cheaper than

chemical agents (48) contributing to

the economy and environment (9, 19, 44).

Several plant

bioactive compounds have shown antimicrobial activity (14). Phenolic-rich

plant extracts have shown significant activity against phytopathogens (22,

42), including Xanthomonas spp., a major threat to crops

like rice and citrus, which have developed resistance to chemicals and

antibiotics (25, 29). Some studies

report the effects of extracts as natural antimicrobials against Xanthomonas

sp. (3, 23, 24, 30).

Other pathogens,

like Clavibacter michiganensis, are responsible for significant losses

in tomato (32), and the bacterium

Erwinia amylovora mainly affects pome fruit trees like pear, apple,

quince, and loquat (5, 28). Carnaval

et al. (2022) observed the inhibition effect of seriguela (Spondias

purpurea L.) extract on Clavibacter michiganensis pv michiganensis

and Xanthomonas phaseoli.

The genus Juglans

includes over 20 species, being J. regia L. majorly significant due

to its extensively studied nutritional and functional properties (7,

15). Walnut by-products, including shells, are rich in bioactive

phytochemicals with antimicrobial potential for medicine, food preservation,

and agroindustry (1, 4, 26, 27). Although their

potential as biopesticides is recognized, the antimicrobial activity of these

compounds is still unexplored. Meanwhile, shell biomass is often undervalued

despite being a cost-effective, renewable resource.

On the other hand, Juglans australis is a native walnut

tree from the Juglandacea family inhabiting the most austral region of South

America, and the Northwestern subtropical rainforest in Argentina, locally

known as “Yungas” (11),

in Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, La Rioja, and Catamarca (figure 1).

Its fruit is an indehiscent, subglobose drupe with a thick, adherent mesocarp

and a rigid shell (endocarp) containing the embryo (39) (figure

1).

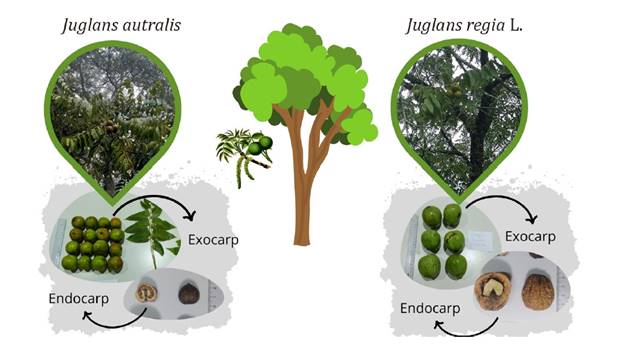

Figure 1. Juglans

australis tree in Ancasti (Catamarca) city,

Argentina (left) and J. regia (right). Morphological comparison of

native J. australis and commercial J. regia L. fruits.

Figura 1 Árbol

y frutos de la especie y Juglans australis (izquierda) y Juglans

regia (derecha), correspondientes a la localidad de Ancasti, provincia de

Catamarca, Argentina.

Contrasting with the extensive knowledge about commercial

walnuts, information on this native species remains scarce. To date, no

research reports antimicrobial or antioxidant activity of Juglans australis;

except for its activity against herpes virus (37).

We

aimed to analyze the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of walnut shell

extracts from the commercial J. regia and the native J. australis for

future uses in agricultural management. These extracts would contribute to

waste valorization while generating added value to the autochthonous species.

Furthermore, extract chemical compositions allowed deeper comprehension of

their bioactive activities.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

In

2021, samples of J. regia and J. australis walnut shells were

collected in Ancasti, Catamarca, Argentina. Walnut shells were cleaned and

dried under shaded conditions for a week. Selected samples were ground into

small particles using a grinder.

Solvent extraction

Solvent

extraction involved 50 g of the powdered walnut shells extracted with 250 mL of

absolute methanol (MeOH) and ethyl acetate (AcOEt) for 45 min at room

temperature and filtered through Whatman n° 4 (48).

The solvents were evaporated under a vacuum in a Büchi R-210 rotavapor. The

extracts obtained were redissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final

concentration of 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/mL and stored in the dark at 4°C for further

use. All extractions were done in duplicate.

Determination of total phenolic content and antioxidant

activities

Total

polyphenol content (TPC) was determined colorimetrically using

Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent at 765 nm. A standard curve was performed with gallic

acid. The results were expressed as μg gallic acid/g dry weight (DW) (41). In

vitro antioxidant activity was measured using the free radical elimination

activity assay on 1,1, -diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazylradical (DPPH) (10),

and ferric reduction capacity of plasma assay (FRAP) (6).

Results are expressed in mmol Trolox equivalents/100 g dry weight (DW). All

samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Identification of extract phenolic compounds by UHPLC-MS/MS

Phenolic compounds

of extracts from walnut shells were identified by a UHPLC (Ultimate 3000 RSLC,

Dionex - Thermo Scientific) equipped with a diode array detector and coupled to

a TSQ Quantum ultra-triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (TSQ Quantum Access

Max, Thermo Scientific) and column Hypersil GOLD aQ (150 x 2.1 mm, 5 um)

(Thermo Scientific). The mobile phase was a binary mixture of solvents: mobile

phase A corresponded to ultrapure water/formic acid solution (Merck, Darmstadt,

Germany) (0.1% v/v), and mobile phase B corresponded to an acetonitrile /

formic acid solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) (0.1% v/v). Gradient

conditions were as follows: 0-18 min, 97% A; 18-21 min, 90% B; 21-26 min, 97%

A. Electrospray source of the MS was performed in negative mode. Eluate was

monitored at 250 nm, flow rate was 0.3 mL min-1, injection volume was 15 μL,

and the column was maintained at 35°C. Polyphenols were tentatively identified

according to their retention times, UV/Vis spectra, high-resolution MS, and

MS/MS spectra by comparison with pure compounds. We searched for gallic acid,

cumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, rutin, and eriocitrin (Sigma-Aldrich,

St. Louis, MO, USA). The linearity of each calibration curve was confirmed by

plotting the ratio of peak areas of phenolic compounds to the internal standard

against compound concentration. Data were analyzed via LC-MS Xcalibur

workstation software (Version 2.6, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activity of the different walnut shell extracts

was evaluated against Gram-negative bacteria Erwinia amilovora, Xanthomonas

axonopodis pv. phaseolus, and X.

campestris pv. campestris 8004 and a Gram positive

bacteria, Clavibacter michiganensis. Bacterial suspensions were prepared

in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB). By microdilution, microtiter plate wells were

filled with bacterial suspension (107 CFU/mL) and the extract solution (final

concentrations 0.1; 1 and 10 mg/ mL). Pure gallic acid, the main extract

component, was incorporated in the antimicrobial assays at three different

concentrations: 34 ppm (higher concentration detected in the extracts), 100

ppm, and 500 ppm. The extracts and gallic acid suspensions were prepared by

diluting stock solutions in DMSO. Vehicle controls were prepared with DMSO and

each bacterial culture. The 1% vehicle did not affect bacterial growth and was

used as negative control. Streptomycin sulfate was also used as positive

control. The microplates were incubated at 28°C for 24 h, and growth was

detected using a microplate reader (Multiskan Go, Thermo) at 560 nm (45).

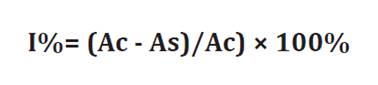

Inhibition percentages were also calculated according to the Equation:

where

Ac

= absorbance of the control sample (phytopathogens without extract and

antibiotic)

As

= absorbance of phytopathogens + extract samples.

All

assays were conducted three times and analyzed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA

and Tukey test evaluated differences between treatments using INFOSTAT

(Student version, 2020e).

Results and discussion

Total Phenolic compounds and Antioxidants activities

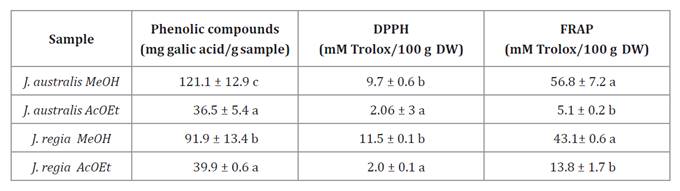

Table 1,

shows total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of organic extracts (ME:

methanolic extract, EAE: ethyl-acetate extract) of J. australis and J.

regia.

Tabla 1. Contenido

fenólico total (TPC), actividades antirradicalias (DPPH) y reductoras (FRAP) de

extractos metanólicos y de acetato de etilo obtenidos a partir del endocarpio

de J. australis y J. regia.

Table 1. Total

phenolic content (TPC), antiradical (DPPH) and reducing (FRAP) activities of

methanolic and ethyl acetate of endocarp extracts from J. australis and J.

regia.

Value is expressed as mean ±

standard error. Different letters indicate statistically significant

differences (p<0.05).

Los valores corresponden a la

media ± error estándar. Letras diferentes indican diferencias estadísticas

(p<0,05).

Solvent extraction capacities varied significantly (p <

0.05). The highest phenolic content and reducing activity were observed in the

methanolic extract corresponding to J. australis (121 mg GAE/g d.w. and

56.8 mmol Trolox/100 g d.w., respectively). However, the strongest antiradical

activity was measured in the methanolic extract of J. regia (p <

0.01).

Methanolic

extracts had the highest total phenols content and the strongest antiradical

and antioxidant activities. Extracts using polar solvents usually exhibit

higher phenolic content and positively correlate with antioxidant potential (48).

Among different factors in the extraction process, total phenolic compounds in

walnut shell varies from 1 mg/g shell to 32.76 mg GAE mg/g shell (2,

26, 48). Here, we obtained 121 mg GAE mg/g shell in methanolic extracts

of J. australis, significantly higher-more than two to ten times-than

the reported (19).

When

DPPH and FRAP activities were analyzed, methanolic extract of J. australis showed

similar activity to J. regia and cited in the literature (42). Yang

et al. (2014) analyzed the antioxidant and antiradical properties of

walnut-shell extracts with different polarity solvents, demonstrating that

methanol also shows the strongest antioxidant activity and reducing power.

These established methods are reliable indicators of antioxidant potential in

the native walnut, comparable with commercial J. regia activities,

making it a potential source of bioactive compounds.

Solvent

selection is crucial for antioxidant isolation by extraction methods. The

chosen solvent significantly affects extract yield and its antioxidant activity

due to the varying polarities of the extracted compounds (31).

Methanolic and ethyl acetate extracts are commonly used in phytochemical

studies. Methanol is a polar solvent that effectively extracts water-soluble

compounds, including phenolics, flavonoids, and alkaloids. Ethyl acetate, on

the other hand, is a less polar solvent that targets more lipophilic compounds,

such as terpenes, steroids, and some fatty acids.

This

difference in composition might depend on the genotype and environmental

conditions during development, and maturity at harvest (2).

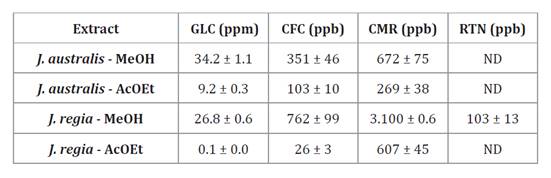

Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds

Phenolic

compounds of walnut shell extract in J. australis and J. regia were

determined using the UHPLC-MS/MS method. Results observed for J. regia extracts

coincide with previous reports (2, 16, 18).

The methanolic extract had the highest concentration of GLC (26.8 mg/L),

followed by CMR (3.1 mg/L) and CFC (762 μg/L). Notably, rutin (RTN) was only

detected in J. regia methanolic extract, albeit at a lower concentration

(103 μg/L). In the ethyl acetate extract of J. regia, the most abundant

were GLC (0.1 mg/L), followed by CMR (607 μg/L) and CFC (μg/L).

RTN in J. regia extracts suggests the potential unique

properties of this species. Studies conducted on several parts of fruit and

leaves consistently reveal that gallic acid is among the most abundant

components in these extracts (2, 16, 18). Fernandez

Argulló et al. (2021) recently reported that

gallic, ellagic, and ferulic acids were the major phenolic compounds in walnut

wood waste extracts. However, our study did not detect ferulic acid.

On the other hand, Gallic acid (GLC), caffeic acid (CFC), and

cumaric acid (CMR) were identified in both J. australis extracts

(methanolic and ethyl acetate) (table 2).

The methanolic extract presents the highest GLC content (34000 μg/L), followed

by CMR (672 μg/L) and CFC (351 μg/L). In ethyl acetate extracts, GLC was most

abundant (9000 μg/L), followed by CMR (269 μg/L) and CFC (103 μg/L). Table 2

shows GLC content was significantly higher than CFC and CMR compounds for both

extracts. Ours is the first characterization and quantification of phenolic

compounds in this native walnut.

Table 2. Phenolic

compounds in walnut shell extracts, and quantitative analysis of phenolic

components in methanolic and ethyl acetate extracts of J. regia and J.

australis.

Tabla 2. Compuestos

fenólicos en extractos de cáscaras de nuez, y análisis cuantitativo del

contenido de componentes fenólicos en extractos de acetato de etilo y

metanólico presentes en J. regia y J. australis.

ppb = parts per billion = μg/L; ppm

= parts per million = mg/L.

Note: AcOEt: ethyl-acetate;

MetOH: methanolic; ppb = parts per billion = μg/L; ppm = parts per million =

mg/L, GLC: gallic acid; CFC: caffeic acid; CMR: cumaric acid; RTN: rutin. ND:

not detectable.

ppb = partes por billón = μg/L; ppm

= partes por millón = mg/L.

Nota: AcOEt: acetato de etilo; MetOH: metanol; LOD:

Límite de detección; ppb = partes por mil millones = μg/L; ppm = partes por

millón = mg/L; GLC: ácido gálico; CFC: ácido cafeico; CMR: ácido cumárico; RTN:

rutin. ND: no detectable.

Since

studies on phenolic compounds are mainly conducted in J. regia, more

information on J. australis extracts is needed. Considering differences

between species, essential in-depth studies would allow understanding

phytochemical profiles while identifying lost or gained compounds during crop

domestication.

Antibacterial activity and gallic acid effects on bacterial

growth

The

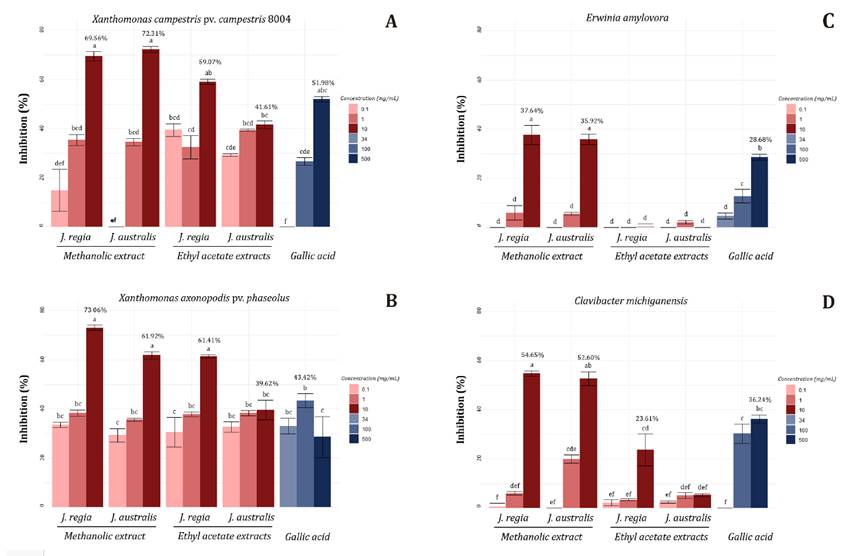

effects of J. regia and J. australis extract and gallic acid

(main compound in all extracts) were evaluated against phytopathogen growth (figure

2). All extracts tested showed the highest inhibition against Xanthomonas

(figure

2 A and B).

Cada

valor se expresa como media ± error estándar. Las diferencias estadísticamente

significativas se indican con letras diferentes (p < 0,01).

Figure

2. Antibacterial activity of shell extracts from

walnuts.

Figura

2 Actividades antibacterianas contra

bacterias fitopatógenos de los diferentes extractos de cáscara de nuez.

For

Xcc 8004, methanolic extracts of J. regia (69.56%) and J.

australis (72.31%) exhibited maximum inhibition at 10 mg/mL. Ethyl acetate

extracts exhibited inhibitory activity against Xcc 8004, with J.

regia demonstrating higher inhibition percentage (59.07%) than J.

australis (41.61%).

All

extracts from both Juglans sp. inhibited Xanthomonas

axonopodis pv. phaseoli, exceeding 40% (figure

2B).

Considering

Erwinia amylovora, methanolic extracts from both species diminished

bacterial development in 37.64% (J. regia) and 35.92% (J. australis)

at the highest tested concentration (figure 2C).

Once

more, methanolic extracts at 10 mg/mL reached 54.65% and 52.60% inhibition

against Clavibacter michiganensis, for J. regia and J.

australis, respectively (figure 2D).

Gallic

acid did not show substantial inhibition on the phytopathogens evaluated. At

the highest concentration, it inhibited X. axonopodis (51.95%) (figure 2).

Other studies mention antimicrobial activity of different parts of J. regia principally

against pathogens of importance in human health (38),

but none on antimicrobial effect against phytopathogens. Here, we observe that

the methanolic extract from walnut shells had the best antimicrobial activity

against the phytopathogens assayed even at the minimum concentration (0.1

mg/mL).

Shell

extracts have inhibitory effects against Xanthomonas sp. and the highest amount of gallic acid (table 2),

probably involved in antibacterial activities. Gallic acid is extensively

studied, and its mechanism of action as an effective antimicrobial is well

known (13, 21, 40).

Vu et al. (2017)

report that gallic acid in walnuts can be found either in its free form or as

part of hydrolyzable tannins. Nevertheless, gallic acid was less effective at

inhibiting the phytopathogens assayed, suggesting a synergistic effect of the

minor components.

Few studies have

examined walnut shell extracts’ antimicrobial effects, typically requiring

higher concentrations (1-100 mg/mL) (31, 32, 44). Several reports

used minimum bactericidal concentrations above 20 mg/mL for J. regia extracts

(43) with notable

activity against gram-negative bacteria like E. coli and P.

aeruginosa (36). In our study,

methanolic extracts effectively inhibited Gram-positive and Gram-negative

phytopathogens at 10 mg/mL, particularly Xanthomonas spp, as previously

reported with extracts from six walnut cultivars against Gram-positive (Bacillus

cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative

bacteria (P. aeruginosa, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae) (34).

Recently, the

search for new natural compounds has gained interest given antioxidant and

antimicrobial properties. Native plants are valued for economic and ecological

benefits, with preservation playing a vital role (22).

The scarce

information about using J. australis phytochemicals evaluates the effect

of leaves and stem extracts on Herpes simplex virus (37). Here, we could

demonstrate the efficacy of the native extracts over various phytopathogens.

Conclusion

In this study, we first report antibacterial activity of

extracts from J. australis against phytopathogenic bacteria, and first

findings on their particular antioxidant and antiradical activities. This

contributions could enhance regional value. This research first characterizes

walnut shell extracts from J. australis. Our findings demonstrate that

methanolic extracts exhibit significant antimicrobial activity against Xanthomonas

sp., suggesting natural biocontrol alternatives to copper-based

formulations.

Acknowledgments

This research

received financial support from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y

Técnica ANPCyT (PICT 2020-03408) and the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones

Científicas y Técnicas, CONICET (PIBAA 0208CO).

The authors are grateful to the researcher, Dr. Osvaldo Delgado (PROIMI),

for providing the bacterial strains used in the antimicrobial assays.

1. Acquaviva, R.;

D’Angeli, F.; Malfa, G. A.; Ronsisvalle, S.; Garozzo, A.; Stivala, A.; Ragusa,

S.; Nicolosi, D.; Salmeri, M. and Genoveseet, C. 2021. Antibacterial and

anti-biofilm activities of walnut pellicle extract (Juglans regia L.)

against coagulase-negative staphylococci. Nat Prod Res. 35(12): 2076-81.

2. Akbari, V.;

Jamei, R.; Heidari, R.; Esfahlan, A. J. 2012. Antiradical activity of different

parts of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) fruit as a function of genotype. Food

Chemistry. 135: 2404-2410.

3. Bajpai, V. K.;

Dung, N. T.; Suh, H. J.; Kang, S. C. 2010. Antibacterial activity of essential

oil and extracts of Cleistocalyx operculatus Bbds against the bacteria

of Xanthomonas spp. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society.

87: 1341-1349.

4. Barekat, S.;

Nasirpour, A.; Keramat, J.; Dinari, M.; Meziane-Kaci, M.; Paris, C.; Desobry,

S. 2022. Phytochemical composition, antimicrobial, anticancer properties, and

antioxidant potential of green husk from several walnut varieties (Juglans

regia L.). Antioxidants. 12(1): 52.

5. Bennet, R. A.;

Billing, E. 1978. Capsulation and virulence in Erwinia amylovora. Annals

of Applied Biology. 89: 41-45.

6. Benzie, I. F.

F.; Strain, J. J. 1996. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a

measure of antioxidant power: The FRAP assay. Analytical Biochemistry. 239:

70-76.

7. Bernard, A.;

Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. 2018. Walnut: past and future of genetic

improvement. Vol. 14. Tree Genetics and Genomes. Springer Verlag.

8. Boiteux, J.;

Espino, M.; Fernández, M. de los Á.; Pizzuolo, P.; Silva, M. F. 2019.

Eco-friendly postharvest protection: Larrea cuneifolia-nades extract

against botrytis cinerea. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 51(2): 427-437.

9. Boiteux, J.;

Fernández, M. de los Á.; Espino, M.; Fernanda Silva, M. F.; Pizzuolo, P. H.;

Lucero, G. S. 2023. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of Larrea

divaricata extract for the management of Phytophthora palmivora in

olive trees. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional

de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 55(2): 97-107. DOI: https://doi. org/10.48162/rev.39.112

10. Brand-Williams,

W.; Cuvelier, M. E.; Berset, C. 1995. Use of a free radical method to evaluate

antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 28: 25-30.

11. Brown, A. D.;

Grau, H. R.; Malizia, L. R.; Grau, A. 2001. In: Kappelle M, Brown AD (eds)

Bosques nublados del neotrópico. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad. Costa

Rica. p 623-659.

12. Carnaval, L. S. C.; Cerboneschi, M.; Tegli, S.; Yoshida, C.

M. P.; Melo, E.; Santos, A. M. P. 2022. Potential agrifood application of seriguela

(Spondias purpurea L.) residues extract and nanoZnO as antimicrobial,

antipathogenic and antivirulence agents. Research, Society and Development 11:

e37211125033. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v11i1.25033

13. Cavalca, L. B.;

Zamuner, C. F. C.; Saldanha, L. L.; Polaquini, C. R.; Regasini, L. O.; Behlau,

F.; Ferreira, H. 2020. Hexyl gallate for the control of citrus canker caused by

Xanthomonas citri subsp citri. Microbiology open. 9: 1-8.

14. Daglia, M. 2012.

Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 23:

174-181.

15. Delaviz, H.;

Mohammadi, J.; Ghalamfarsa, G.; Mohammadi, B.; Farhadi, N. 2017. A review study

on phytochemistry and pharmacology applications of Juglans regia plant. Phcog Rev. 11: 145-52.

16.

Fernández-Agulló, A.; Castro-Iglesias, A.; Freire, M. S.; González-Álvarez, J.

2020. Optimization of the extraction of bioactive compounds from walnut (Juglans

major 209 x Juglans regia) leaves: Antioxidant capacity and phenolic

profile. Antioxidants. 9: 4-6.

17.

Fernández-Agulló, A.; Freire, M. S.; Ramírez-López, C.; Fernández-Moya, J.;

González-Álvarez, J. 2021. Valorization of residual walnut biomass from forest

management and wood processing for the production of bioactive compounds.

Biomass Convers Biorefin. 11(2): 609-18.

18. Hu, Q; Liu, J.;

Li, J.; Liu, H.; Dong, N.; Geng, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y. 2020. Phenolic

composition and nutritional attributes of diaphragma juglandis fructus and

shell of walnut (Juglans regia L.). Food Sci Biotechnol. 29(2): 187-96.

19. Hussain, T.;

Singh, S.; Danish, M.; Pervez, R.; Hussain, K.; Husain, R. 2020. Natural

Metabolites: An eco-friendly approach to manage plant diseases and for better

agriculture farming. In natural bioactive products in sustainable agriculture.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981- 15-3024-1_3

20. INFOSTAT

Analytical Software version 2020e. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Córdoba.

Argentina.

21. Krol, E.; De

Sousa Borges, A.; Da Silva, I.; Polaquini, C. R.; Regasini, L. O.; Ferreira,

H.; Scheffers, D. J. 2015. Antibacterial activity of alkyl gallates is a

combination of direct targeting of FtsZ and permeabilization of bacterial

membranes. Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 390.

22. Lorenzo, M. E.;

Casero, C. N.; Gómez, P. E.; Segovia, A. F.; Figueroa, L. C.; Quiroga, A.;

Werning, M. L.; Wunderlin, D. A.; Baroni, M. V. 2020. Antioxidant

characteristics and antibacterial activity of native woody species from

Catamarca, Argentina. Nat Prod Res. DOI: 10.1080/14786419.2020.1839461.

23. Luján, E. E.;

Torres-Carro, R.; Fogliata, G.; Alberto, M. R.; Arena M. E. 2019. Fungal

Extracts as Biocontrol of Growth, Biofilm Formation, and Motility of Xanthomonas

citri subsp. citri. Global Journal

of Agricultural Innovation, Research & Development. 6: 25-37.

24. Macioniene, I.;

Cepukoit, D.; Salomskiene, J.; Cernauskas, D.; Burokiene, D.; Salaseviciene, A.

2022. Effects of Natural Antimicrobials on Xanthomonas Strains Growth.

Horticulturae. 8: 7.

25. Mansfield, J.;

Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.;

Verdier, V.; Beer S. V.; Machado, M. A. 2012. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria

in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13: 614-629.

26. Masek, A.;

Latos-Brozio, M.; Chrzescijanska, E.; Podsedek, A. 2019. Polyphenolic profile

and antioxidant activity of Juglans regia L. leaves and husk extracts.

Forests. 10: 988. doi:10.3390/f10110988

27. Mateș, L.;

Rusu, M. E.; Popa, D. S. 2023. Phytochemicals and Biological Activities of

Walnut Septum: A Systematic Review. J Antioxidants. 12(3): 604.

28. Merlin, E.;

Lopez, J.; Sarmiento, H. 2014. Control del tizón del fuego en manzano. Folleto

Técnico Núm. 73. INIFAP.

29. Miller, S. A.;

Ferreira, J. P.; Lejeune, J. T. 2022. Antimicrobial use and resistance in plant

agriculture: A one health perspective. Agriculture (Switzerland). 12(2): 1-27.

30. Mohana, D. C.;

Raveesha, K. A. 2006. Antibacterial activity of Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq.)

Willd. against plant pathogenic Xanthomonas

pathovars: an ecofriendly approach. Journal of Agricultural Technology. 2:

31.

31. Moure, A.;

Cruz, J. M.; Franco, D.; Domínguez, J. M.; Sineiro, J.; Domínguez, H. 2001.

Natural antioxidants from residual sources. Food Chem. 72: 145-171.

32. OEPP/EPPO.

2005. Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis.

Bull. OEPP-EPPO Bull. 35: 275-283.

33. Oliveira, I.;

Sousa, A.; Ferreira, I. C. F. R.; Bento, A.; Estevinho, L.; Pereira, J. A.

2008. Total phenols, antioxidant potential and antimicrobial activity of walnut

(Juglans regia L.) green husks. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 46:

2326-2331.

34. Pereira, A. P.;

Ferreira, C. F. R.; Marcelino, F, Valentao, P.; Andrade, P.; Seabra, R.;

Estevinho, L.; Bento A.; Pereira, J. A. 2007. Phenolic compounds and

antimicrobial activity of olive (Olea europaea L. Cv. Cobrançosa)

leaves. Molecules. 12: 1153-1162.

35. Pontes, J. G.

D. M.; Fernandes, L. S.; dos Santos, R.; Tasic, L.; Fill, T. P. 2020. Virulence

factors in the Phytopathogen-Host Interactions: An overview. Journal of

Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 68: 7555-7570.

36. Raaman, N.; Mathiyazhagan,

K.; Jegadeesh, R.; Divakar, S.; Vennila, S.; Balasubramanian, K. 2011.

Antimicrobial activities of different organic extracts of nut shells of Juglans

regia (walnut). Herbal Tech Industry. 20: 22.

37. Ruffa, M. J.; Wagner, M. L.; Suriano, M.; Vicente, C.;

Nadinic, J.; Pampuro, S.; Salomón, H.; Campos, R. H.; Cavallaro, L. 2004.

Inhibitory effect of medicinal herbs against RNA and DNA viruses. Antiviral

Chemistry and Chemotherapy. 15(3): 153-159. https://doi.

org/10.1177/095632020401500305

38. Sandu-Bălan,

A.; Ifrim, I. L.; Patriciu, O. I.; Ștefănescu, I. A.; Fînaru, A. L. 2024.

Walnut by-products and elderberry extracts-sustainable alternatives for human

and plant health. Molecules. 29(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29020498

39. Sharma, M.;

Sharma, M.; Sharma. M. 2022. A comprehensive review on ethnobotanical,

medicinal and nutritional potential of walnut (Juglans regia L.).

Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s43538-022-00119-9

40. Silva, I. C.;

Polaquini, C. R.; Regasini, L. O.; Ferreira, H.; Pavan, F. R. 2017. Evaluation

of cytotoxic, apoptotic, mutagenic, and chemo- preventive activities of

semi-synthetic esters of gallic acid. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 105:

300-307.

41. Singleton, V.

L.; Rossi, J. A. 1965. Colorimetry of total phenolics with

phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 16: 144-158.

42. Soto-Maldonado,

C.; Caballero-Valdés, E.; Santis-Bernal, J.; Jara-Quezada, J.; Fuentes-Viveros,

L.; Zúñiga-Hansen ME. 2022. Potential of solid wastes from the walnut industry:

Extraction conditions to evaluate the antioxidant and bioherbicidal activities.

Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 58: 25-36.

43. Vieira, V.;

Pereira, C.; Abreu, R. M.; Calhelha, R. C.; Alves, M. J.; Coutinho, J. A. P.;

Ferreira, O.; Barros L.; Ferreira ICFR. 2020. Hydroethanolic extract of Juglans

regia L. green husks: A source of bioactive phytochemicals. Food and

Chemical Toxicology. 137: 111189. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2020.111189

44.

Villamil-Galindo, E.; Piagentini, A. 2024. Green solvents for the recovery of

phenolic compounds from strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch) and apple

(Malus domestica) agro-industrial bio-wastes. Revista de la Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 56(1):

149-160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.131

45. Viola, C. M.;

Torres-Carro, R.; Cartagena, E.; Isla, M. I.; Alberto, M. R.; Arena, M. E. 2018.

Effect of wine wastes extracts on the viability and biofilm formation of Pseudomonas

aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Evidence-Based

Complementary and Alternative Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9526878

46. Vu, T. T.; Kim,

H.; Tran, V. K.; Vu, H. D.; Hoang, T. X.; Han, J. W.; Choi, Y. H.; Jang, K. S.;

Choi, G. J.; Kim J. C. 2017. Antibacterial activity of tannins isolated from Sapium

baccatum extract and use for control of tomato bacterial wilt. PLoS ONE.

12: 1-12.

47. Yabalak, E.;

Erdogan Eliuz, E. A. 2021. Green synthesis of walnut shell hydrochar, its

antimicrobial activity and mechanism on some pathogens as a natural sanitizer.

Food Chemistry. 366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130608

48. Yang, J.; Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Ge, F.; Liu, D. 2014. Effect

of solvents on the antioxidant activity of walnut (Juglans regia L.)

s.hell extracts. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research. 2: 621-626.