Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. En prensa. ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Original article

Epiphytic

microorganisms associated with banana phyllosphere with potential antagonism to

Black Sigatoka (Pseudocercospora fijiensis) in Los Ríos, Ecuador

Identificación

de microorganismos epífitos asociados a la filósfera de banano con potencial

antagonismo a Sigatoka Negra (Pseudocercospora fijiensis) en la

provincia de Los Ríos, Ecuador

Solanyi Marley Tigselema Zambrano1*,

Aracelly Mabel Villalba Puga2,

Jim Raphael Ochoa Ramos1,

Galo Efraín Lara Hidalgo1,

Diana Aracelly López1

1 Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias. Mocache.

Ecuador. C. P. 120310.

2 Universidad de Las Américas. Facultad de Ingeniería y Ciencias

Aplicadas. Quito. Ecuador. C. P. 170124.

* solanyi.tigselema@iniap.gob.ec

Abstract

Black Sigatoka (Pseudocercospora

fijiensis) is the most important leaf spot disease of bananas worldwide,

particularly affecting Cavendish banana, the most exported variety.

Additionally, this pathogen has developed resistance to some effective fungicides,

making its management increasingly difficult. Epiphytic microorganisms with

potential antagonism to P. fijiensis were identified in conventional

banana farms in the province of Los Ríos. Sampling areas were determined

through zoning processes and selecting the cantons of Mocache, Valencia, Baba

and Pueblo Viejo. Leaf tissue samples were collected from three farms per zone.

Microorganisms were isolated and morphologically and molecularly characterised

in nine farms in the cantons of Valencia (63 bacteria), Baba (39 bacteria),

Pueblo Viejo (8 bacteria) and 8 genera of fungi including 15 species. The

isolated bacteria presented macroscopic and microscopic characteristics with

different shapes, elevations, edges, consistencies and pigmentations. Taxonomically,

they belonged to the genera Bacillus and Cocos, 81% Gram-negative

and 19% Gram-positive. The analysis conducted for sampling-site selection

allowed the identification of different microbial behaviours.

Keywords: microorganisms,

fungi, bacteria, Musa spp.

Resumen

Sigatoka negra es

la enfermedad de la mancha foliar más importante del banano a nivel mundial. La

variedad de banano Cavendish, es considerada la más común y la más exportada;

sin embargo, presenta una alta susceptibilidad frente a la enfermedad. Existen

fungicidas altamente efectivos para su control; sin embargo, el patógeno ha

logrado generar resistencia a algunos de estos, lo que ha dificultado cada vez

más su manejo. Se identificaron microorganismos epífitos con potencial

antagonismo a Pseudocercospora fijiensis en fincas de banano

convencionales de la provincia de Los Ríos. Las zonas de muestreo fueron

determinadas a través de procesos de zonificación, seleccionando los cantones

Mocache, Valencia, Baba y Pueblo Viejo. Se recolectó muestras de tejido foliar

en tres fincas por zona. Se aislaron microorganismos y se caracterizaron

morfológica y molecularmente en nueve fincas en los cantones de Valencia (63

bacterias), Baba (39 bacterias) y Pueblo Viejo (8 bacterias) y 8 géneros de hongos

que incluyen 15 especies. Las bacterias aisladas presentaron características

macroscópicas y microscópicas con diversas formas, elevaciones, bordes,

consistencias y pigmentaciones, así como diversas taxonomías pertenecientes a

los géneros Bacillus y Cocos, siendo 81% Gram negativas y 19% Gram

positivas. El análisis realizado para la selección de los sitios de muestreo

fue apropiado ya que se observó un comportamiento diferencial de los

microorganismos en estas zonas.

Palabras claves: microorganismos, hongos,

bacterias, Musa spp.

Originales: Recepción: 21/08/2024

- Aceptación: 06/03/2025

Introduction

Musaceae is a family of

monocotyledonous plants that include bananas and plantains, often called giant

herbs (31). These plants belong to the genus Musa,

cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions (36).

The banana sector

in Ecuador has 167,893 hectares, with a productivity of 6,684,916

tons. Los Ríos province has the highest participation in the national

production of fresh fruit with 38.47% (2 571 356 t), with a contribution of 1

328 537 964.98 US dollars (45).

Investment in

production and related industries (goods and services needed for banana

production) and the current banana export process created jobs for more than

one million households in Ecuador, benefiting around 2.5 million people in nine

provinces heavily dependent on the banana industry. Compared to other non-oil

sectors in the country, this sector is the backbone of economic activity,

generating higher incomes and providing more employment opportunities (16).

Black Sigatoka is

the most economically important leaf spot disease of Musaceae, affecting

many plantations and resulting in forced early harvesting (27). This disease is

caused by the fungus Pseudocercospora fijiensis, exclusive of banana

foliage with sexual and asexual reproduction. It infects the plants, hindering

photosynthesis and causing gradual leaf necrosis and death. Disease severity is

determined by the Stover scale modified by Benavides-López (2019), Gauhl

(1994)

and Muimba-Kankolongo

(2018).

Black Sigatoka is

mainly controlled by technical management and appropriate fungicide rotation.

However, given climatic variability, the disease shows different behaviours

around the country. Los Ríos province is the most affected, with 74% of

production losses. Twenty-two to 29 annual aerial spraying cycles are used to

fight the disease, representing costs between $430 and $800 (8,

9). In addition, surgical practices like excision of mottled areas

and leaf removal are carried out (9, 17).

International

markets for plant protection products are dominated by synthetic pesticides (30). These chemical

substances seriously affect the ecosystem and induce resistance, altering

ecological equilibriums (28). Therefore,

searching for alternative control strategies is relevant worldwide (24).

The search for

antagonistic microorganisms for biological control of pathogens in economically

important crops has aroused particular interest due to their potentialities (4,

54). Microorganisms of agricultural importance represent a key ecological

strategy towards the integrated development of practices such as nutrient,

disease and pest management, reducing chemicals and improving crop yield (42).

Several microorganisms showing beneficial effects on plants may constitute

potential biocontrol agents (3, 41) and important

actors in sustainable agriculture (51).

Biological control

of Black Sigatoka has received relatively little attention due to the

availability of highly effective fungicides. However, the emergence of pathogen

isolates resistant to systemic fungicides and the need for cleaner production

technologies have increased interest in biological control (22).

The search for

effective biological products against this disease has studied different

microorganisms associated with these crops (12). Therefore, this

research aimed to collect, isolate and characterise microorganisms from the

phyllosphere of Musaceae.

Materials

and methods

Study

area

This research was

conducted at the Pichilingue Tropical Experimental Station (EETP) of the

National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIAP) with samples obtained from

conventional banana farms of Cavendish Williams cultivar in the cantons of

Mocache, Valencia, Baba and Pueblo Viejo, Los Ríos province.

Field

methodology

Sampling sites were

chosen by zoning with cartographic charts from the IGM (Military Geographic

Institute) database. The climate micro-zonation map was generated by satellite

images with ArcGIS 10.8, at a scale of 1:25 000 for geo pedological conditions

considering soil pH, organic matter and surface texture, with 1:50 000 scale,

considering geopedology, geomorphology, CUT (soil usage capacity) and isotherms,

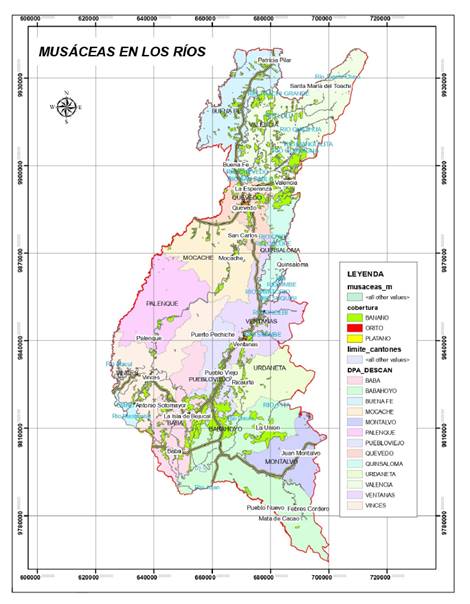

including climatic zones, temperature and cover use (figure 1).

Figure 1. Climate

micro-zonation map for sampling sites in the Province of Los Ríos, generated by

ArcGIS 10.8 software.

Figura

1. Mapa de microzonificación climática

para sitios de muestreo en la Provincia de Los Ríos, generado con el software

ArcGIS 10.8.

Ten subsamples were

collected from each farm, constituting one composite sample. In selected

plants, the third and fourth leaves were identified for tissue to be obtained

from the central third, both on the right and left side of the midrib. Samples

were identified by recording origin and date (41).

Fungal

identification from leaf tissue was conducted in Mocache, Baba and Pueblo

Viejo. Bacteria were identified from leaves in Valencia, Baba and Pueblo Viejo.

Microorganism

isolation

For the isolation

of bacteria, the samples obtained were processed according to Intriago

Mendoza (2010). Agar culture medium was prepared in flasks, sterilised in autoclave

for 30 minutes and distributed in petri dishes. Twenty-five g of leaf tissue

were washed in 100 mL of sterile distilled water (SDW). Product water was used

for serial dilutions up to -3. One ml of each dilution was seeded by Digralsky

loop, and plates were incubated at room temperature for 5 days for growth

evaluation.

In order to isolate

fungi, plant tissue samples were washed with distilled water, cut into small

portions of tissue (3 to 5 mm) and immersed in a 1-3% hypochlorite solution for

one minute, followed by rinsing with sterile water. Tissue portions were seeded

in Petri dishes with PDA (potato dextrose agar) + chloramphenicol medium and

incubated at 28°C for 5 days. Isolates were purified and preserved at 5°C (20).

Morphological

characterization

After biochemical

Gram staining and catalase tests, macroscopic and microscopic characterisation

was carried out on the isolated microorganisms, described by their shape,

colour, edges, elevation and consistency (52).

Number

of Colonies

Number of colonies on the plates is expressed as CFU/ml (Colony

Forming Units) according to Casas et al. (2017).

Extraction

of fungal genomic DNA

According to Doyle & Doyle (1987) modified by Faleiro

et al. (2002), samples were split into two boxes per sample with 14 daysqold

mycelium and triturated with liquid nitrogen. The homogenate was mixed with 800

μL extraction buffer (7% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide [CTAB], 5 M NaCl, 0.5

mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 1 M Tris-HCl pH = 8,

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40), 1% (v/v) ß-mercaptoethanol and milliQ water).

Five μL of proteinase K (concentration 20 mg/uL) was added to the homogenate

and incubated at 65°C for 1 hour in a water bath. Then, it was centrifuged at

14 000 rpm for 15 minutes and the supernatant was collected into 2 mL tubes,

added 55 μL of 7% CTAB and 700 μL chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (25: 1; v: v),

mixed with inversion and vortexed until an emulsion was formed and centrifuged

at 14 000 rpm for 16 minutes. Again, the supernatant was extracted to 2 mL

tubes by adding 700 μL chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (25: 1; v: v), mixed and

centrifuged. The supernatant was recovered in 1.5 mL tubes and 700 μL (2/3 of

the tube) was added with ice-cold absolute ethanol (-20°C), for storage at

-20°C for 1 to 2 hours. Centrifugation was performed at 14 000 rpm for 5

minutes, obtaining a white pellet and the supernatant was removed by washing

the pellet 3 to 4 times with 70% ethanol at -2°C. (500 μL). Finally, the pellet

was dried in a thermoblock at 55°C and DNA was resuspended in 100 μL of TE with

RNAsa (concentration 20 mg/ml).

PCR

Amplification of Ribosomal ITS Region

To verify the

extracted DNA, amplification was performed with markers ITS1

(TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG) and ITS4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATATGC) and the amplification

cocktail proposed by Morillo & Miño (2011). All samples were

amplified on the Applied Biosystems thermal cycler in a total reaction volume

of 25 μl, including 2.50 μL of 5x Green GoTaq® Flexi Buffer (Promega), 1.5μL of

MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.50 μL of dNTPs (5mM), 2 μL of each primer (5 μmol), 0.50 μL of

DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific DreamTaq) (5 U/ μl), 1 μL of genomic DNA (5

ng/ μl) and 15 μL of ultrapure water. PCR included initial denaturation at 95°C

for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min,

hybridisation at 55°C for 2 min, elongation at 72°C for 1 min and a final

elongation step at 70°C for 10 min.

DNA amplicons were

analysed on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel using Syber Safe for 30 minutes at 100V.

Amplicon sizes were estimated by comparison with a TrackIt™ 1 Kb Plus DNA

Ladder molecular weight marker and visualised in a photodocumenter.

Sequence

analysis

PCR products were

shipped to the research laboratories of the Universidad de las Américas (UDLA),

according to the university guidelines, which consisted of 10 μL of PCR

product, 2 μL of each primer (ITS 1/ ITS4) (2 μM concentration) per sample and

cold chain storage at 4°C or below. Sequence editing was performed using the

Unipro UGENE software and the BLAST programme at the Centro Nacional de

Información Biotecnológica (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to obtain consensus

sequences. Sequence alignment was performed by MUSCLE algorithm with MegaX

software. The matrix obtained was used to assemble the phylogenetic tree based

on the Maximum-Likelihood (ML) algorithm, with genetic distance calculated by the

Jukes-Cantor model, Bootstrap-100 and Uniform Rates.

Results

Colony

count

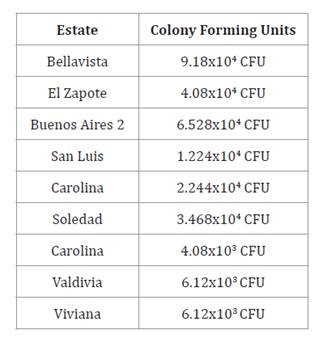

Considering the three farms evaluated in each canton, in

Valencia, the Bellavista farm had the highest number of colonies with 9.18x104

CFU; in Baba the Soledad farm had the highest number of colonies

with 3.468x104 CFU and in Pueblo Viejo,

Valdivia and Viviana farms had 6.12x103 CFU,

obtaining a total of 63 bacteria in Valencia, 39 bacteria in Baba and 8

bacteria in Pueblo Viejo.

Strain

characterisation

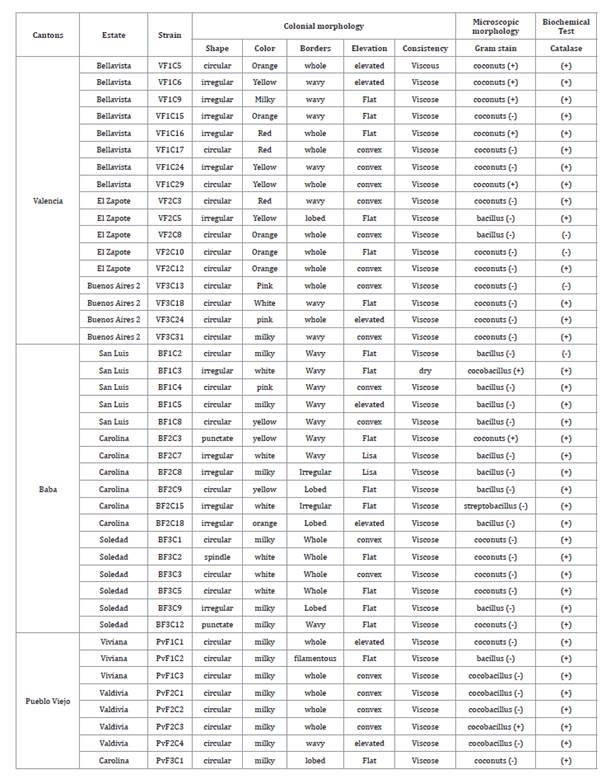

Colonial morphological characterisation, microscopic morphology

and biochemical tests were performed on the bacteria isolated in the province

of Los Ríos (table

1).

Table 1. Characterisation

of microorganisms associated with the banana phyllosphere, Los Ríos province.

Tabla

1. Caracterización de microorganismos

asociados a la filósfera de banano, provincia de Los Ríos.

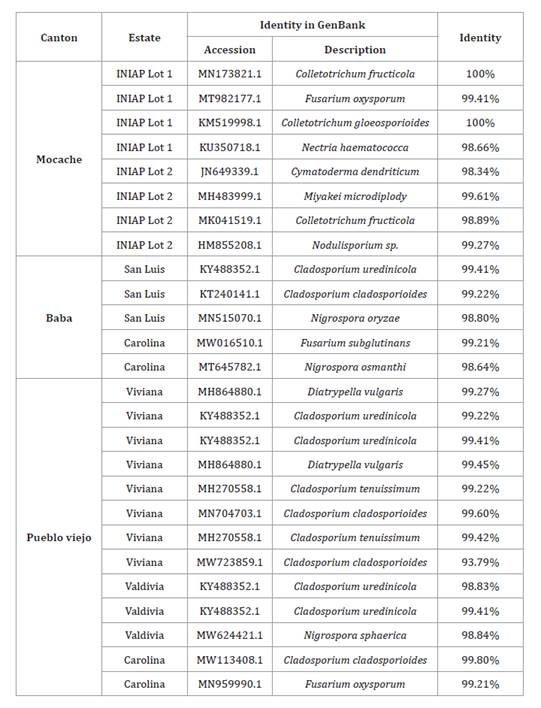

Eight fungal strains were isolated in Mocache, 5 in Baba and 13

in Pueblo Viejo. Eight PCR products were amplified from Mocache, 5 from Baba

and 13 from Pueblo Viejo. Twenty-six sequences were obtained. Similarity

percentages were 90-100 % with NCBI homologous sequences (table 2).

Table 2. Collection

and ITS rDNA sequences of fungi isolated in the cantons of Mocache, Baba and

Pueblo Viejo.

Tabla

2. Detalles de la colección y

secuencias ITS del ADNr de hongos aislados en los cantones de Mocache, Baba y

Pueblo Viejo.

The identified fungi were from the genera Fusarium sp., Colletotrichum

sp., Diatrypella sp., Nodulisporium sp., Nigrospora sp.,

Microdiplodia sp., Cymatoderma sp. and Cladosporium

sp. Fusarium sp. is a candidate biological

control agent against Pseudocercospora fijiensis. Nodulisporium sp. is an endophyte capable of producing insecticidal

nodilosporic acids and volatile antifungal substances (Suwannarach

et al., 2013). Nigrospora sp. produce

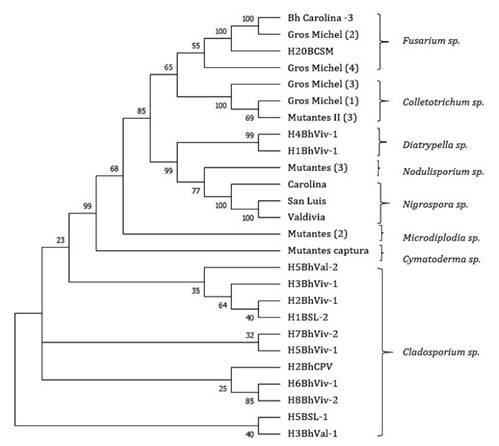

bioactive secondary metabolites with antifungal activity (23) (figure 2).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic

tree of fungal isolates associated with banana phyllosphere with potential

antagonism to Black Sigatoka in the cantons of Mocache, Baba and Pueblo Viejo.

Phylogenetic construction by Maximum- Likelihood method, Jukes-Cantor

model, Bootstrap-100 and Uniform Rates.

Figura

2. Árbol filogenético de aislamientos

de hongos asociados a la filósfera de banano con potencial antagonismo a

Sigatoka Negra en los cantones de Mocache, Baba y Pueblo Viejo. Construcción filogenética

por el método Maximum-Likelihood, Jukes-Cantor model, Bootstrap-100 y Uniform

Rates.

Discussion

Fungal disease

control mainly relies on the application of agrochemicals. However, this

practice causes pathogen resistance after prolonged application, generating

public concern about the effects of toxic residues on human health and the

environment.

This research identified Bacillus bacteria. According to Cruz-Martín

et al. (2018) Bacillus pumilus CCIBP-C5 decreases fungal biomass,

induces phytodefense mechanisms in the plant, and may constitute a potential

biological control agent against P. fijiensis. Based on this finding, B.

pumilus CCIBP-C5 constitutes a guideline for further research.

Contrary to other

studies, proportions of Gram-negative bacteria (81%) exceeded that of

Gram-positive bacteria (19%). Previously, Ceballos et al. (2012) found higher

proportions of Gram-positive bacteria (67%) than Gram-negative bacteria from

three banana and plantain cultivars in Urabá (Northwest Colombia). Regarding

the inhibitory capacity of the isolated microorganisms, the results showed that

Bacillus bacteria have antagonistic activity against the fungus P.

fijiensis, as seen by Villegas-Escobar et al. (2013) when isolating 649

strains of aerobic endospore-forming bacteria. The strain Bacillus subtilis showed

the highest inhibition (89±1%), proving its bioactive potential against P.

fijiensis.

After isolation,

colonies showed different shapes (circular, pointed, irregular, spindle),

elevations (flat, convex, smooth, raised), edges (entire, wavy, lobulated,

irregular, filamentous), consistencies (viscous, dry) and pigmentations

(orange, yellow, red, pink, milky, white), as reported by Alfaro

(2013)

when isolating and quantifying epiphytic bacteria from the banana phylloplane Musa

AAA cv. Grande Naine.

Considering the 26

isolated fungi, 25 belonged to Ascomycota and one to Basidiomycota. Ascomycota

fungi grow in subtropical conditions, as bananas (44).

Fungal molecular

identification is frequently assessed with the internal transcribed spacer

(ITS) region (47). The primers ITS1

and ITS4 have broad utility and presence in universal databases, with

successful amplification rates of fungal lineages (53). Based on in

silico analysis (49) the primer ITS1 represents

73.8% of Ascomycota and 85.6% of Basidiomycota in the SSU region, while the

primer ITS4 represents 97.6% in Ascomycota and 96.9% in Basidiomycota in the

LSU region. This means ITS primers allowed amplifying sequences from both

Ascomycota and Basidiomycota fungi.

In a study of

pathogenic taxa in wild banana (Musa acuminata), Brown et

al. (1998) identified potential endophytic pathogen genera and species

that may remain dormant, such as Colletotrichum sp. and

Nigrospora sp. Zakaria & Aziz (2018) isolated fungi of

the genus Nigrospora sp., Fusarium sp. and

Colletotrichum sp. on bananas. Very similar

results were obtained by Horra (2014) and in the present study, including Diatrypella

sp., Nodulisporium sp., Microdiplodia sp., Cymatoderma sp.

and Cladosporium sp.

Fusarium oxysporum is present among

the rhizosphere microflora, and some strains cause wilting or total root rot of

banana plants (19). It should be

noted that all F. oxysporum strains are saprophytes, surviving for long

periods in both soil organic matter and the rhizosphere. This possibly explains

their latent presence in leaf tissue and the sampled areas. We also isolated Nectria

haematococca (sexual morph of F. solani), a filamentous type of

fungus. F. solani is part of a complex with 60 phylogenetic species (46). These two Fusarium

sp. strains could constitute candidate biological

control agents against P. fijiensis (2), encouraging

future antagonistic tests for evaluations against black Sigatoka.

Colletotrichum sp. predominates in the tropics and subtropics with heavy

rainfall and high relative humidity (43). Two species were

found in this study, C. gloeosporioides and C. frutícola. The

former causes banana anthracnose and leaf spot (38), while C. frutícola

has been identified on mango plants (29). One of the main

characteristics of Colletotrichum sp. infection

in bananas is the difficulty in detecting the disease before fruit generation,

given latency (37).

Diatrypaceae members like the

genus Diatrypella are saprobes and pathogens associated with different

hosts in both terrestrial and aquatic environments (14). Species of this

genus are separated according to their entostrophic morphology and the number

of ascospores they present (50). Fungal

pathogenicity is moderate for this genus. This study firstly reports Diatrypella

vulgaris, in banana. However, it is commonly isolated from diseased Vitis

vinifera, causing necrotic lesions on the plant (40).

The fungal isolate Nodulisporium

sp. produces nodilosporic acids with insecticidal

properties and volatile antifungal substances used against other microorganisms

through mycofumigation (48).

Fungi of Nigrospora sp. are

host-specific phytopathogenic, endophytic and saprophytic species that produce

bioactive secondary metabolites with antifungal activity (23). During

isolations, N. sphaerica and N. osmanthi were isolated from the

environment. N. sphaerica exhibits a violent spore-discharging mechanism

that projects spores over long distances (57). Similarly, Nigrospora

oryzae and N. sphaerica were identified from banana leaves (58). This study also

firstly reports N. osmanthi in bananas.

Isolated fungi of

the genus Microdiplodia sp. and Cymatoderma sp.

have not previously been recorded in bananas. However,

Pinheiro

da Costa et al. (2021) detail the presence of Microdiplodia sp. with antifungal activity on Brugmansia suaveolens and Cymatoderma

sp. as the only Basidiomycota reported in tropical

rainforest (1).

Finally, the genus Cladosporium

sp. comprises more than forty species, including

pathogenic species causing leaf spot and saprophytic species acting on

vegetation and soil (35). Isolated C.

cladosporioides confirms this fungus as an endophyte isolated from foliar

culture tissues of banana plants (58). In addition, C.

uredinicola, also isolated in this study, presents small conidia formed

with branched chains that facilitate its propagation over long distances (6), explaining its

higher prevalence over other fungi. Another species identified, C. tenuissimum

is an abundant saprobe in the tropics (56). Moubasher

et al. (2016) state that the frequency of Cladosporium sp. isolation is moderate and peaks during winter, when humidity

benefits banana development.

Conclusions

Considering the

differential behavior of microorganisms and the number of strains found in the

studied sites, the analysis focused on selecting sampling sites was

appropriate.

The isolated microorganisms presented macroscopic and

microscopic characteristics with different shapes, elevations, borders,

consistencies and pigmentations. Different taxonomies belonged to the Bacillus

and Coccus genera, 81% being Gram-negative and 19% Gram-positive.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the technical staff of the National

Agricultural Research Institute, who provided their scientific contribution

during the development of the research.

1. Agudelo, M. B.;

Calderón, M.; Betancourt, O.; Gallejo, Á. S. 2007. Hongos Macromycetes en dos

rellictos de bosque húmedo tropical montano bajo de la vereda La Cuchilla.

Marmato, Caldas. Museo de História Natural. 11: 19-31.

2. Alfaro, F. 2013.

Aislamiento y cuantificación de bacterias epífitas del filoplano de banano

(Musa AAA cv. Grande Naine) y selección de cepas quitinolíticas y

glucanolíticas como potenciales antagonistas de Mycosphaerella fijiensis,

agente causal de la Sigatoka negra.

3. Ayala, D.;

Acevedo, C.; Enrique, B.; Aguilar, F.; Orlandoni, G. 2018. Seguimiento de la

actividad PGPR de microorganismos inoculados en plantas de Sacha inchi (Plukenetia

volubilis) bajo condiciones de vivero. Archivo digital de prácticas,

Microbiología Industrial. Universidad de Santander UDES. 1-14.

https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.25676.36489

4. Barrera, S.;

Sarango, S.; Montenegro, S. 2019. The phyllosphere microbiome and its potential

application in horticultural crops. A review. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias

Hortícolas. https://revistas.uptc.edu.co/index.php/ciencias_horticolas/article/view/8405

5. Benavides-López,

L. 2019. Cuantificación temprana de Pseudocercospora fijiensis por medio

de qPCR en modelos predictivos de Sigatoka negra en plantas de banano (Musa

AAA). 9-162.

6. Bensch, K.; Braun,

U.; Groenewald, J. Z.; Crous, P. W. 2012. The genus Cladosporium. Studies in

Mycology. 72(1): 1. https://doi.org/10.3114/SIM0003

7. Brown, K.; Hyde,

K.; Guest, D. 1998. Preliminary studies on endophytic fungal communities of Musa

acuminata species complex in Hong Kong and Australia. https://www. fungaldiversity. org/fdp/sfdp/FD_1_27-51.pdf

8. Carrión Abad, B.

A. C. 2015. Análisis microbiológico del complejo orgánico activfol para

determinar la efectividad en el control del hongo (Mycosphaerella fijiensis)

causante de la Sigatoka negra en el banano.

9. Carrion Ramon,

J. J. C. 2020. Monitoreo y control especial de la Sigatoka negra (Mycosphaerella

Fijiensis M), en el cultivo de banano. UTMACH. Unidad Académica de Ciencias

Agropecuarias. Machala. Ecuador.

http://repositorio.utmachala.edu.ec/handle/48000/16135

10. Casas, J.;

López, M.; Salinas, M.; Gisbert, J.; Giménez, E.; García, F.; Sánchez, S.;

Lacalle, A.; Cortés, A.; Moyano, F. 2017. Guía para la realización de un

estudio ambiental: El caso de la cuenca del río Adra (J. Casas, Ed.; Vol. 11).

Universidad de Almería. 3qk3vTP

11. Ceballos, I.;

Mosquera, S.; Angulo, M.; Mira, J.; Argel, L.; Uribe-Velez, D.; Romero-Tabarez,

M.; Orduz-Peralta, S.; Villegas, V. 2012. Cultivable bacteria populations

associated with leaves of banana and plantain plants and their antagonistic

activity against Mycosphaerella fijiensis. Microbial Ecology. 64(3):

641-653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-012-0052-8

12. Cruz-Martín, M.; Acosta-Suárez, M.; Roque, B.; Pichardo, T.;

Castro, R. 2016. Diversidad de cepas bacterianas de la filosfera de Musa spp. con actividad antifúngica frente a Mycosphaerella

fijiensis Morelet. Biotecnología Vegetal. 16(1): 53-60.

13. Cruz-Martín,

M.; Alvarado, Y.; Mena, E.; Acosta, M.; Roque, B.; Pichardo, T. 2018. Cepas

bacterianas con potencial para el manejo de la Sigatoka negra. Anales de la

Academia de Ciencias de Cuba. 8(1).

http://www.revistaccuba.sld.cu/index.php/revacc/article/view/374/373

14. Dissanayake, L.

S.; Wijayawardene, N. N.; Dayarathne, M. C.; Samarakoon, M. C.; Dai, D. Q.;

Hyde, K. D.; Kang, J. C. 2021. Paraeutypella guizhouensis gen. et sp. nov. and Diatrypella

longiasca sp. nov. (Diatrypaceae) from China. Biodiversity Data Journal 9:

e63864. https:// doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.9.E63864

15. Doyle, J. J.;

Doyle, J. L. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for samal quantities of

fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin. 19: 11-15.

16. Ecuador, M. de

C. E. del. 2017. Informe Sector Bananero Ecuatoriano. Ministerio de Comercio

Exterior. 53(9): 1689-1699. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

17. Etebu, E.;

Young-Harry, W. 2011. Control of black Sigatoka disease: Challenges and

prospects. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 6(3): 508-514.

https://doi.org/10.5897/ AJAR10.223

18. Faleiro, F. G.;

Santos, I. S.; Bahía, R.; Santos, R. F.; Anhert, D. 2002. Otimização da

extração e amplificação de DNA de Theobroma cacao L. visando obtenção de

marcadores RAPD. 31- 34.

19. Fravel, D.;

Olivain, C.; Alabouvette, C. 2003. Fusarium oxysporum and its

biocontrol. New Phytologist. 157(3): 493-502.

https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1469-8137.2003.00700.X

20. García, F.;

Pachacama, S.; Jarrín, D.; Iza, M. 2020. Guía andina para el diagnóstico de

Fusarium Raza 4 Tropical (R4T) Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. Cubense (syn. Fusarium

odoratissimum) agente causal de la marchitez por Fusarium en

musáceas (plátanos y bananos). www.

comunidadandina.org

21. Gauhl, F. 1994.

Epidemiology and ecology of Black Sigatoka on plantain and banana (Musa spp.)

in Costa Rica, Centro América. Ph.D. Thesis of the Systematisch

Geobotanische-Institut der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen and Institut für

Pflanzenpathologie und Pflanzenchutz der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen.

INIBAP.

22. Guzmán, M.

2012. Control biológico y cultural de la sigatoka-negra. Tropical Plant

Pathology. 37 (Suplemento). Agosto. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2927.7442

23. Hao, Y.;

Aluthmuhandiram, J. V. S.; Chethana, K. W. T.; Manawasinghe, I. S.; Li, X.;

Liu, M.; Hyde, K. D.; Phillips, A. J. L.; Zhang, W. 2020. Nigrospora species

associated with various hosts from Shandong Peninsula, China. Mycobiology.

48(3): 169-183. https://doi. org/10.1080/1229 8093.2020.1761747

24.

Hernández-Montiel, L. G.; Larralde-Corona, C. P.; Vero, S.; López-Aburto, M.

G.; Ochoa, J. L.; Ascencio-Valle, F. 2010. Caracterización de levaduras Debaryomyces

hansenii para el control biológico de la podredumbre azul del limón

mexicano. CYTA-Journal of Food. 8(1): 49-56.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19476330903080592

25. Horra, M. L. P.

2014. Evaluación in vitro de la capacidad de extractos orgánicos de

biodiversidad ecuatoriana para inhibir al patógeno Mycosphaerella fijiensis (Morelet)

causante de la Sigatoka Negra en banano.

http://repositorio.puce.edu.ec/bitstream/ handle/22000/10936/4.42.000892.pdf?sequence=4

26. Intriago

Mendoza, L. 2010. Identificación y evolución en laboratorio e invernadero de

microorganismos antagonistas de Sigatoka negra (Mycosphaerella fijiensis

Morelet) en musáceas en el Litoral Ecuatoriano. Tesis de Grado. Universidad

Técnica de Manabí. Ecuador. 95 p.

27. Israeli, Y.;

Lahav, E. 2016. Banana. In Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences. Elsevier. 3:

363-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394807-6.00072-1

28. Izzeddin, A.

N.; Medina, T. L. 2011. Efecto del control biológico por antagonistas sobre

fitopatógenos en vegetales de consumo humano. Salus. 15(3): 8-18.

29. Lima, N. B.;

Marcus, M. V.; Morais, M. A. D.; Barbosa, M. A. G.; Michereff, S. J.; Hyde, K.

D.; Câmara, M. P. S. 2013. Five Colletotrichum species are responsible for

mango anthracnose in northeastern Brazil. Fungal Diversity. 61(1): 75-88.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225- 013-0237-6

30. López, S. 2019.

Bacillus un género que alberga especies que cumplen diversos roles biológicos.

Infive-Conicet UNLP. 1-26.

31. Martínez, G.;

Pargas, R.; Manzanilla, E. 2012. Orden Zingiberales: Las musáceas y su relación

con plantas afines. Scielo.

http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0002-

192X2012000100014

32. Morillo, E.;

Miño, G. 2011. Marcadores moleculares en biotecnología agrícola: manual de

técnicas y procedimientos en INIAP.

https://repositorio.iniap.gob.ec/bitstream/41000/848/4/ iniapscm91.pdf

33. Moubasher, A.

H.; Moharram, A. M.; Ismail, M. A.; Abdel-Hafeez, M. H. 2016. Aeromycobiota

over banana plantations in Assiut Governorate and enzymatic producing potential

of the most common species. Journal of Basic & Applied Mycology (Egypt). 7:

9-18.

34. Muimba-Kankolongo, A. 2018. Fruit Production. In Food crop

production by smallholder farmers in Southern Africa (p. 275-312). Elsevier.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814383- 4.00012-8

35. Nam, M. H.;

Park, M. S.; Kim, H. S.; Kim, T. I.; Kim, H. G. 2015. Cladosporium

cladosporioides and C. tenuissimum cause blossom blight in

strawberry in Korea. Mycobiology. 43(3): 354.

https://doi.org/10.5941/MYCO.2015.43.3.354

36. Novák, P.;

Hřibová, E.; Neumann, P.; Koblížková, A.; Doležel, J.; Macas, J. 2014.

Genome-wide analysis of repeat diversity across the family musaceae. PLoS ONE.

9(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0098918

37. Nuangmek, W.;

McKenzie, E. H. C.; Lumyong, S. 2008. Endophytic fungi from wild banana (Musa

acuminata Colla) works against anthracnose disease caused by Colletotrichum

musae. Research Journal of Microbiology. 3(5): 368-374. https://doi.

org/10.3923/ JM.2008.368.374

38. Photita, W.;

Lumyong, S.; Lumyong, P.; Mckenzie, E. H. C.; Hyde, K. D.; Photita, W.;

Lumyong, S.; Lumyong, P.; Hyde, M. E. H. C. 2004. Fungal diversity are some

endophytes of Musa acuminata latent pathogens? Fungal Diversity. 16:

131-140.

39. Pinheiro da

Costa, S.; Schuenck-Rodrigues, R.; da Silva Cardoso, V.; Valverde, S.;

Vermelho, A.; Ricci-Júnior, E. 2021. Actividad antimicrobiana de hongos

endofíticos aislados de Brugmansia suaveolens Bercht.; Presl, J.

Research, Society and Development. 10(14): e113101421646. https://doi.

org/10.33448/rsd-v10i14.21646

40. Pitt, W. M.;

Trouillas, F. P.; Gubler, W. D.; Savocchia, S.; Sosnowski, M. R. 2013.

Pathogenicity of Diatrypaceous Fungi on grapevines in Australia. Plant disease.

97(6): 749-756. https:// doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-10-12-0954-RE

41. Poveda, I.;

Cruz-Martín, M.; Sánchez-García, C.; Acosta-Suárez, M.; Leiva-Mora, M.; Roque,

B.; Alvarado-Capó, Y. 2010. Caracterización de cepas bacterianas aisladas de la

filosfera de Musa spp. con actividad antifúngica in

vitro frente a Mycosphaerella fijiensis. Biotecnología Vegetal.

10(1): 57-61.

42. Ramírez, M.;

Rodriguez, T.; Peniche, C.; Alfonso, L. 2010. Chitin and its derivatives as

biopolymers with potential agricultural applications. Biotecnología Aplicada.

27: 270-276.

43. Riera, N. J.

2015. Caracterización molecular y de patogenicidad de Colletotrichum spp,

en bananas var Cavendish y pruebas de antagonismo con Trichoderma spp.,

recolectadas en fincas bananeras de la región costa del Ecuador. Universidad

San Francisco de Quito. 98.

44. Ruiz-Boyer, A.;

Rodríguez-González, A. 2020. Preliminary list of fungi (Ascomycota and

basidiomycota) and myxomycetes (myxomycota) of Isla del Coco, Puntarenas, Costa

Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical. 68(S1): S33-S56.

https://doi.org/10.15517/RBT. V68IS1.41165

45. SIPA. 2021.

Ficha del cultivo de banano (Musa paradisiaca AAA).

https://sipa.agricultura.gob.ec/ index.php/bananos

46. Šišić, A.;

Baćanović-Šišić, J.; Al-Hatmi, A. M. S.; Karlovsky, P.; Ahmed, S. A.; Maier,

W.; Hoog, G. S. D.; Finckh, M. R. 2018. The ‘forma specialis’ issue in Fusarium:

A case study in Fusarium solani f. Sp. Pisi. Scientific Reports 2018

8:1, 8(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018- 19779-z

47. Sun, X.; Guo,

L. D. 2012. Endophytic fungal diversity: Review of traditional and molecular

techniques. Mycology. 3(1): 65-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2012.656724

48. Suwannarach,

N.; Kumla, J.; Bussaban, B.; Nuangmek, W.; Matsui, K.; Lumyong, S. 2013.

Biofumigation with the endophytic fungus Nodulisporium spp. CMU-UPE34 to

control postharvest decay of citrus fruit. Crop Protection. 45: 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/J. CROPRO.2012.11.015

49. Toju, H.;

Tanabe, A. S.; Yamamoto, S.; Sato, H. 2012. High-Coverage ITS Primers for the

DNA-Based Identification of Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes in Environmental

Samples. PLoS ONE. 7(7): 40863. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0040863

50. Trouillas, F.

P.; Úrbez-Torres, J. R.; Gubler, W. D. 2017. Diversity of diatrypaceous fungi

associated with grapevine canker diseases in California. 102(2): 319-336.

https://doi.org/10.3852/08- 185

51. Vázquez, J.;

González, J.; Castillo, J.; Álvarez, M. 2019. Microorganismos benéficos MOBs

obtenidos de plantas, como promotores en la germinación de semillas. Dominio de

Las Ciencias. 5: 615-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.23857/dc.v5i1.1064 Cie

52. Velasco, R.;

Tapia, R. 2014. Curso práctico de Microbiología. Universidad Autónoma

Metropolitana.

53. Vilgalys, R.

2003. Taxonomic misidentification in public DNA databases. New Phytologist.

160(1): 4-5. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1469-8137.2003.00894.X

54. Villamil

Carvajal, J. E. V.; Viteri Rosero, S. E. V.; Villegas Orozco, W. L. V. 2015.

Aplicación de antagonistas microbianos para el control biológico de Moniliophthora

roreri Cif & Par en Theobroma cacao L. bajo condiciones de

campo. Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín. 68(1): 7441-7450.

https://doi.org/10.15446/rfnam.v68n1.47830

55.

Villegas-Escobar, V.; Ceballos, I.; Mira, J. J.; Argel, L. E.; Peralta, S. O.;

Romero-Tabarez, M. 2013. Fengycin C produced by Bacillus subtilis EA-CB0015.

Journal of Natural Products. 76(4): 503-509. https://doi.org/10.1021/np300574v

56. Walker, C.; Muniz, M. F. B.; Rolim, J. M.; Martins, R. R.

O.; Rosenthal, V. C.; Maciel, C. G.; Mezzomo, R.; Reiniger, L. R. S. 2016.

Morphological and molecular characterization of Cladosporium cladosporioides

species complex causing pecan tree leaf spot. Genetics and molecular

research: GMR. 15(3). https://doi.org/10.4238/GMR.15038714

57. Wang, M.; Liu,

F.; Crous, P. W.; Cai, L. 2017. Phylogenetic reassessment of Nigrospora:

Ubiquitous endophytes, plant and human pathogens. Persoonia: Molecular

Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 39(December). 118-142.

https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2017.39.06

58. Zakaria, L.; Aziz, W. N. W. 2018. Molecular Identification

of endophytic fungi from banana leaves (Musa spp.). Tropical Life Sciences

Research. 29(2): 201. https://doi.org/10.21315/ TLSR2018.29.2.14