Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. En prensa. ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Original article

Critical

Point Analysis for Sustainable Management of Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera:

Tortricidae) in Smallholder Walnut Farms of Catamarca, Argentina

Análisis

de Puntos Críticos en la Sustentabilidad del Manejo de Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera:

Tortricidae) en Pequeñas Producciones Nogaleras de Catamarca, Argentina

María José Cavallo1,

Oscar Eduardo Romero4,

Braian Vladimir Sosa1,

Martin Sebastian Espinosa5, 6,

1Centro Regional de Energía y Ambiente para el Desarrollo

Sustentable (CONICET-UNCA). Laboratorio de Control Biológico y Biodiversidad de

Insectos. C. P. 4700. Prado 366. Catamarca. Argentina.

2Universidad Nacional de Tucumán. Facultad de Ciencias Naturales

e Instituto Miguel Lillo. Instituto de Investigaciones de Biodiversidad Argentina.

C. P. 4000. Miguel Lillo 251. Tucumán. Argentina.

3Universidad Nacional de Catamarca. Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Cátedra Cultivos Industriales. Depto. Producción Vegetal. C. P. 4700.

Av. Belgrano 300. Catamarca. Argentina.

4Universidad Nacional de Catamarca. Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Cátedra Climatología agrícola. Depto. Clima, Suelo y Riego.

Catamarca. Argentina.

5Universidad Nacional de Chilecito. Departamento de Ciencias

Básicas y Tecnológicas. C. P. 5360. 9 de Julio 22. Chilecito. La Rioja.

Argentina.

6Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas.

C1425FQB. Godoy Cruz 2290. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Abstract

In Argentina, 80%

of walnut production is carried out by smallholder farms facing poor technology,

production constraints, and substantial economic losses due to pests like Cydia

pomonella (codling moth). We assessed sustainability risks linked to

phytosanitary management on small farms in the Ambato region of Catamarca,

Argentina. Our analysis included a “strong sustainability” framework with three

key dimensions: ecological, economic, and sociocultural. A total of 26

indicators were related to this species’ management. Using semi-structured

interviews, visual aids, and field surveys across seven farms, an overall

sustainability index of 1.521 was calculated, with 50% of the indicators

scoring below the established threshold (on a five-level sustainability scale,

the selected threshold was level two). The ecological dimension emerged as the

most sustainable. Limitations included absent systematic monitoring and

optimisation of treatment timing, solely with agrochemical control, weak

farmer-to-farmer collaboration, and insufficient training opportunities.

Cluster analysis revealed four distinct groups based on phytosanitary

practices. This study highlights critical intervention points and suggests

agroecological strategies to enhance sustainable pest management in smallholder

walnut systems.

Keywords: codling moth,

Phytosanitary management, sustainability, Juglans regia

Resumen

En Argentina, el

80% del sector nogalero está representado por pequeños productores, con bajo

nivel tecnológico, limitaciones en la producción y presencia de especies plaga

como Cydia pomonella (“carpocapsa”), entre otros. Se evaluaron los

riesgos a la sustentabilidad del manejo fitosanitario de C. pomonella en

minifundios de Ambato (Catamarca, Argentina), considerando tres dimensiones:

ecológica, económica y sociocultural, bajo un enfoque de sustentabilidad

fuerte. Se identificaron 26 indicadores relacionados con el manejo de esta

especie. Mediante encuestas semiestructuradas, cartillas visuales y

relevamientos en siete fincas, se determinó un Índice de sustentabilidad

general de 1.521, con el 50% de los indicadores por debajo del umbral

establecido (de una categorización de sustentabilidad según una escala de cinco

puntos, el valor umbral seleccionado fue de dos). La dimensión ecológica fue la

más destacada en términos de sustentabilidad. Las limitaciones encontradas en la

práctica fitosanitaria incluyeron la falta de monitoreo de C. pomonella que

definan momentos oportunos de control, el uso de agroquímicos como única

herramienta de control, ausencia de interacción entre productores y falta de

capacitaciones en fitosanidad. Mediante análisis de clúster se evidenciaron

cuatro grupos según sus prácticas fitosanitarias. Se detectaron puntos críticos

y propusieron herramientas para promover prácticas agroecológicas para un

manejo sustentable.

Palabras clave: carpocapsa, manejo

fitosanitario, sustentabilidad, Juglans regia

Originales: Recepción: 28/02/2025

- Aceptación: 21/07/2025

Introduction

Developing

sustainable agriculture requires long-term flow of goods and services to meet

nutritional, socio-economic, and cultural needs, within biophysical limits

defined by the natural system supporting production. Sustainability encompasses

multiple, interrelated objectives that demand multidisciplinary approaches (44, 50). Understanding sustainability enables

evaluating and mitigating production-based environmental impacts, while

accounting for market fluctuations and supply chain vulnerabilities (21). Sustainable systems must be productive,

stable, resilient, and adaptable, distributing costs and benefits equitably and

fostering autonomous decision-making among stakeholders (3).

Agricultural

landscapes are not isolated. Production units and the environment constitute a

continuous agroecosystem. Native vegetation refuges natural enemies of insect

pests, supporting biodiversity. Ecological services like biotic regulation,

nutrient cycling, and pollination must be managed to maintain a dynamic

equilibrium between native and introduced components (32). This management depends on farmers’

knowledge and decisions (49).

Walnuts (Juglans

regia L.) represent a major agricultural sector in Argentina. Catamarca

province ranks second in national walnut production, with 4063 hectares

cultivated and 2619.9 tonnes annually (47).

The sector comprises a range of production systems, from large-scale farms

(20%) to smallholder (80%) (29, 32, 37).

These last producers manage fewer than five hectares with limited technological

inputs and modest yields. Challenges such as water scarcity, labour shortage,

and high logistical costs hinder sustainable practices in the region. Changes

in organization of the productive sector related to financing and

self-management affect marketing (16).

One productivity

constraint is the codling moth (Cydia pomonella (Linnaeus, 1758);

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), a major pest responsible for 40% to 60% yield losses

(14). Larvae penetrate fruit after

hatching, causing economic damage. Conventional management relies on

calendar-based applications of organophosphates and pyrethroids (8), which have led to pest resistance,

environmental and biodiversity degradation while risking human health (19). Alternative control strategies, including

mating disruption, biopesticides, and parasitoid-based biological control, have

not been widely adopted (10, 18, 25).

Transitioning

towards sustainable agriculture needs robust methodologies for sustainability

assessment. These assessments must be context-sensitive, cost-effective, and

capable of identifying critical constraints at different spatial scales (field,

farm, region). Since sustainability is a multidimensional concept, it is

summarized through indicators (43, 44).

In this way, subjective and objective indicators are measured, with the latter

recorded independently of what the farmer reports (e.g., vegetation

cover). Two main approaches characterize sustainability. Weak sustainability

allows substituting natural capital with human-made capital, while strong

sustainability sees both as complementary and irreplaceable (15, 21, 38, 43). This work adopted the strong

sustainability perspective.

In Catamarca,

previous research has addressed data on walnut varietals, types of farmers and

biological aspects of C. pomonella (16, 32,

39, 41). To date, one study has assessed sustainability of walnut

production, incorporating economic, ecological, and social dimensions within an

agroecological framework (24), but no

study has dealt with pest sustainable management. This study assessed the risks

to sustainable phytosanitary management of C. pomonella by smallholder

walnut farmers in Ambato (Catamarca). We employed a set of indicators and

semi-structured interviews to evaluate three sustainability dimensions. (a)

Ecological: Spontaneous vegetation within walnut crops supports diverse and

structurally complex habitats for natural enemies of C. pomonella. (b)

Economic: Financial losses from pest damage may exceed profits, compromising

economic viability. (c) Sociocultural: Farmers largely operate in isolation and

often lack knowledge about pest biology and management strategies.

This multidimensional

evaluation provides insights into opportunities and constraints for sustainable

pest management in smallholder agroecosystems and proposes future strategies

for ecological intensification and rural resilience.

Methodology

Study

Area

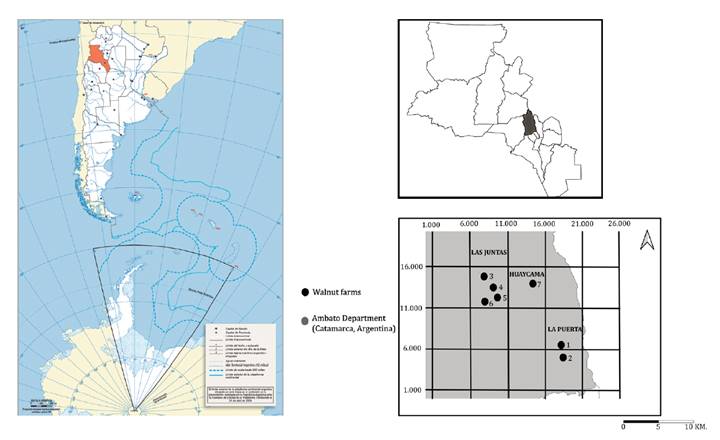

The study was conducted in the Ambato Department (28°10’14” S,

65°47’29” W) in Catamarca Province, Argentina, where seven smallholder walnut

farms were selected as observational units (figure 1). Farms

were chosen by considering average walnut production in the area and confirmed

presence of C. pomonella. These farms exhibit notable varietal

diversity, with predominant traditional ‘Criolla’ seed type and recently

introduced lateral-bearing cultivars like ‘Chandler’.

Figure

1. Study area. Walnut farms in Ambato,

Catamarca, Argentina.

Figura

1. Área de estudio. Fincas de

nogales en Ambato, Catamarca, Argentina.

Indicator

Development, Standardization, and Weighting

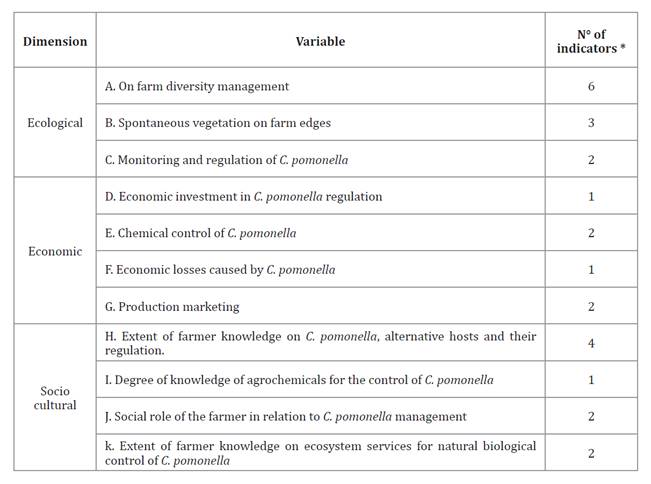

Indicators were developed following Sarandón

and Flores (2009). Table 1 shows eleven key variables

related to phytosanitary management of C. pomonella, each associated

with specific response indicators, yielding 26 sustainability indicators (Supplementary

Material 1). Each indicator was scored on a five-point ordinal scale,

ranging from 0 (least sustainable) to 4 (most sustainable), with 2 as

analytical threshold. Relative weights were assigned to each indicator based on

its perceived importance within the system. This weighting process was

conducted through expert consensus in our research team (Supplementary

Material 1).

Table 1. Composition

of the sustainability analysis of Cydia pomonella management in walnut

farms.

Tabla

1. Composición del análisis de

sustentabilidad del manejo de Cydia pomonella en fincas de nogales.

*

Details of each indicator and its categorization in Supplementary

Material 1.

*

Detalles de cada indicador y su categorización en Material

Suplementario 1.

Estimation

of Subjective Indicators in Economic and Sociocultural Dimensions

Categorical values

of subjective indicators were determined after individual semi-structured

interviews with the seven walnut producers between October 2023 and June 2024.

The questionnaire comprised 114 questions and was supplemented by two

illustrated booklets. These visual materials assessed farmers’ ability to

distinguish C. pomonella from other insects like Lepidoptera, Diptera,

and Coleoptera, including natural enemies (Supplementary

Material 2).

Estimation

of Objective Indicators in the Ecological Dimension

Field-based

ecological assessments were conducted on each farm. These included: (a)

Vegetation characterization: number of plant species, cultivated and

spontaneous, within each orchard and along field margins during autumn and

spring. Species identification was conducted using field guides and images.

Particular interest was given to Fabaceae, Asteraceae, and Apiaceae families,

known to enhance the presence of natural enemies of C. pomonella (34, 35). (b) Vegetation cover was

estimated using the square sampling method (33).

Five points per farm were randomly selected, corresponding to cardinal and

central sectors (M1: North; M2: East; M3: South; M4: West; M5: center). At each

point, 0.25 m² sampling squares were defined. Within these units, species were

recorded and vegetation cover was quantified. (c) Proximity to spontaneous

vegetation and habitat connectivity considered the distance from ten walnut

trees per farm, randomly selected, to the nearest patch of spontaneous

vegetation. Mean distance per farm was calculated.

Data Analysis

Each farm was

treated as an independent unit (20),

allowing for in-depth, contextual analysis and extrapolation to the broader

regional context. Five categorical sustainability levels assigned to each

response identified the most influential sustainability indicators as not

sustainable (0%, score 0), weak (25%, score 1), moderate (50%, score 2),

optimal (75%, score 3), and strongly sustainable (100%, score 4) (1). A weighted average per indicator was

calculated by combining farmer proportion providing each response with the

corresponding sustainability score (1, 44).

The resulting values were used to generate sustainability profiles by dimension

(ecological, economic, sociocultural) for each farm, and to calculate a General

Sustainability Index (GSI) for the study area. Farms scoring above the

threshold value of 2 were considered optimally sustainable. Equations for

indicator weighting, scoring, and index calculation are provided in Supplementary

Material 1. Finally, a multivariate cluster analysis (27) grouped farms according to shared indicator

profiles, eliminating variables with low discriminatory power. Correlations

among farm groups identified patterns of sustainability performance.

Results

and discussion

Ecological

Dimension. Indicator Variability and Biodiversity Management

Based on

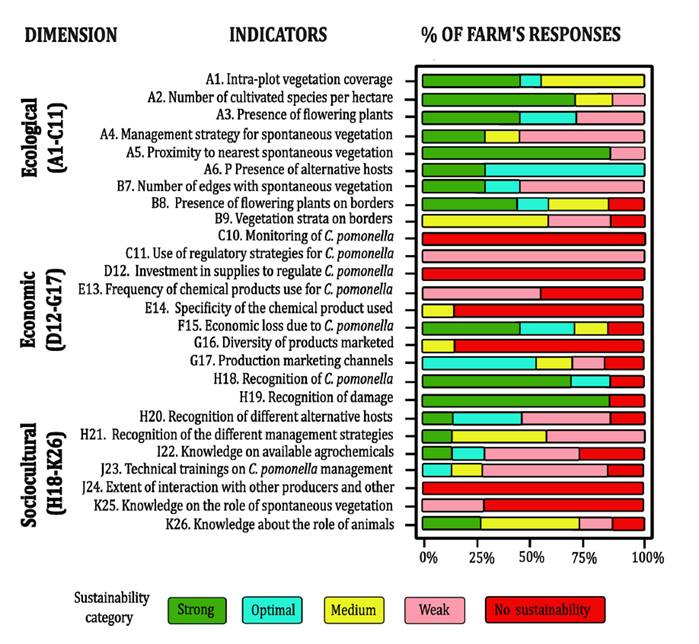

farmer-reported data and field measurements, ecological indicators showed the

greatest variability among the three evaluated dimensions (figure

2, variables 1-11).

Figure

2. Percentage distribution of indicator sustainability

based on farmer responses (%). All indicators are related to Cydia pomonella

recognition and control.

Figura

2. Gráfico de distribución del porcentaje de

sustentabilidad de cada indicador considerando el porcentaje de respuestas de

los productores. Todos los indicadores están en función de Cydia pomonella,

su reconocimiento y control.

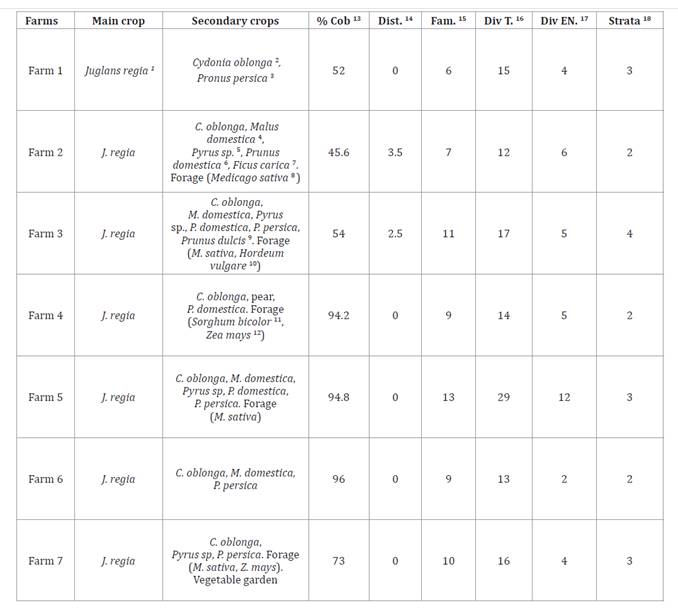

Ecological

diversity management revealed moderate to high habitat complexity (table

2). Vegetation cover across farms ranged from 45% to 95%, and mean distance

to the nearest spontaneous vegetation during spring-summer was under one meter.

A total of 29 plant species from 13 botanical families were identified across

the farms. However, only 12 of these species belonged to families previously

documented as favourable for natural enemies of C. pomonella (23) (table 2).

Table 2. Ecological

diversity on study farms.

Tabla

2. Diversidad ecológica en las fincas de estudio.

1.

Walnut. 2. Quince. 3. Peach. 4. Apple tree. 5. Pear tree. 6. Plum tree. 7. Fig

tree. 8. Alfalfa. 9. Almond tree. 10. Barley. 11. Sorghum. 12. Corn. 13.

Average percentage of vegetation cover on the farm. 14 Average distance from

the walnut tree to the nearest spontaneous vegetation. 15. Number of families.

16. Total number of species. 17. Number of species belonging to the families

Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Apiaceae: attractive to natural enemies (EN). 18.

Number of vegetation strata.

1.

Nogal. 2. Membrillo. 3. Durazno. 4. Manzano. 5. Peral. 6. Ciruelo. 7. Higo. 8.

Alfalfa. 9. Almendro. 10. Cebada. 11. Sorgo. 12. Maíz. 13. Promedio de

porcentaje de cobertura vegetal dentro de la finca. 14. Distancia promedio del

nogal a la vegetación espontánea más cercana. 15. Número de familias. 16.

Número de especies total. 17. Número de especies que pertenecen a las familias

Fabaceae, Asteraceae y Apiaceae: atractivos para enemigos naturales (EN). 18.

Cantidad de estratos.

Notable species

included Convolvulus arvensis L. (bindweed), Aloysia gratissima G.

& H. (whitebrush), Taraxacum officinale L. (dandelion), Melilotus

albus M. (white sweet clover), and Ammi visnaga L. (toothpick

plant). Notably, plant spatial and temporal distributions do not result from

intentional management. Rather, they establish spontaneously, primarily along

farm boundaries, which may adjoin other orchards, natural landscapes, or, in

some cases, expanding urban zones.

Across farms, vegetation stratification ranged from two to four

layers, suggesting a potentially favourable microhabitat structure for natural

enemy communities, enhancing biological control potential. Despite this, field

observations and expert communications (Engineers Romero and Barros, pers.

comm.) indicate low abundance and diversity of natural enemies in the study

area, including Goniozus legneri Gordh (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae), an

effective parasitoid of several lepidopteran pests, including C. pomonella (5, 10, 31). Several factors may account for this

discrepancy. Recent urban expansion in the Ambato Department may have

influenced these results (11). This area,

formerly dedicated to livestock production, has undergone changes that may have

negatively affected soil quality and reduced the availability of potential

refuges for natural enemies. The replacement of natural vegetation likely

eliminated important sources of food and shelter for beneficial fauna,

disrupting the natural landscape and ecological balance. Residual effects of agrochemicals

accumulated over recent decades, mainly pyrethroids used for C.

pomonella control, could also contribute to these outcomes (6). In this regard, Ferrero

and collaborators (2000) demonstrated the detrimental impact of organophosphates

and pyrethroids on G. legneri, reporting reductions in longevity,

oviposition capacity, and egg-laying size. Similarly, Leyton

(2023) documented the harmful effects of several insecticides (Bifenthrin,

Pirimicarb, Imidacloprid) on this parasitoid species. Without adequately

monitoring pest precise emergence, chemical treatments lose effectiveness,

often resulting in repeated applications. Such practices disturb ecosystem

balance, reduce functional biodiversity, and compromise long-term ecological

sustainability. Moreover, they may contribute to developing resistant pest

populations and pose risks to human health.

Walnuts were the primary crop across all farms, accompanied by

11 secondary species, including fruit and forage crops (table 2).

A common association was observed with Cydonia oblonga (quince), an

alternative host for C. pomonella, with important implications for

integrated pest management strategies. However, farmer perceptions of C.

oblonga varied. In this study producers generally regarded quince as a

low-priority crop, “not needing targeted control measures”. Some even suggested

it could constitute a trap distracting C. pomonella away from walnut

fruits. This contrasts with Rivero et al. (2012)

from Andalgalá (Catamarca), where farmers actively managed C. pomonella in

quince to prevent its migration into walnut orchards. These divergent

approaches highlight the need for context-specific education on host dynamics

and pest ecology.

The weakest

ecological sustainability indicator was absent C. pomonella monitoring,

essential for understanding population dynamics and their effects on crop

yield. Yet, extensive evidence supports the critical role of pest monitoring

combined with systematic data analysis, enhancing effectiveness and

sustainability of integrated pest management programs (12). Farmers reported not monitoring insects or

fruit damage, nor estimating number of damaged fruits per season (figure

2, indicators C10 and C11). This limits timely and effective control

strategies.

Economic

Dimension: Sustainability Constraints in C. pomonella Management

The economic

analysis revealed absent monitoring as a major limit for sustainable C.

pomonella management. No farmer reported investing in monitoring (figure 2, D12). As a result, chemical control remains

predominant across most farms, applied according to calendar schedules and

without rotation of active ingredients (figure 2, E13 and

E14). This facilitates the emergence of resistant pest populations, already

documented in fruit-producing regions like Alto Valle (Río Negro, Neuquén) (12, 48), Chile and South Africa (7, 46). The penetration of neonate C.

pomonella larvae into fruit makes post-infestation chemical treatments

ineffective. Consequently, pest control must be precisely timed. Monitoring

adult population and fruit damage, managing damage thresholds, and tracking

degree-day accumulation to anticipate pest emergence have proved most effective

(4, 22). However, government-led

phytosanitary campaigns often proceed without prior monitoring and on

broad-spectrum insecticides applied at high doses, further undermining

sustainability. Previous studies in the Andalgalá region have evaluated

insecticide use on walnut farms and emphasized the importance of reducing

environmental and worker exposure, rotating active ingredients with distinct

modes of action, and incorporating at least one compound that preserves

beneficial insect populations (8, 9).

Despite this, some farms in Ambato report no pest control, citing costly

supplies as primary barrier.

Economic losses

attributed to C. pomonella (figure 2, F15) are

approximately 20% for half of the producers, and between 20% and 50% for the

second half, consistent with Andalgalá (42).

Only one producer reported losses exceeding 80%. In apple production (Malus

domestica), a 1% fruit damage threshold per hectare has been established as

economic injury level (13). However, no

standardized threshold exists for walnuts. Preliminary research by our group

suggests a 4% fruit loss threshold, provided monitoring is conducted regularly

(Diez, pers. comm.). These thresholds imply that the sustainability assessment

scale used in this study should be adjusted to reflect crop-specific economic

realities more accurately, enhancing control relevance.

Alternative

cultural and biological strategies remain underutilized. While collecting and

destroying infested fruit (e.g., by burning) is recognized as a general

pest control practice (36), surveyed

farmers reported this approach primarily for land clearing. In addition, the

use of corrugated cardboard bands to trap diapausing larvae, a low-cost method

to reduce first-generation adult populations (4),

is neither considered. Biological inputs, such as C. pomonella granulovirus

(CpGV), have shown promising results among traditional growers in Pomán and

Andalgalá (40), not yet in Ambato.

Additional economic

indicators detected problems related to a lack of productive diversity (figure 2, G16 and G17). Most farms only sell peeled and shelled

walnuts in bulk, often at very low prices. Developing value-added products,

such as candied walnuts called “nueces confitadas”, walnut oil, or walnut

paste, enhances farm income and economic resilience. Similar marketing

innovations have been observed in other walnut-growing regions of Catamarca,

including Belén and Pomán (field interviews; Poncho Festival 2024, Catamarca).

Sociocultural

Dimension: Insights into Knowledge and Systemic Challenges

Interview data

revealed low sociocultural sustainability risk, as most farmers demonstrated

basic knowledge of C. pomonella biology and field behavior (figure

2, H18-H2; table 2). This knowledge is valuable, as

sustainable pest control requires understanding the pest’s life cycle and its

interaction with the host (2).

Participants identified the pest, recognized typical damage signs, and

estimated seasonal presence in their orchards. However, as already mentioned,

this knowledge is not consistently translated into practice (figure

2, D12, H21, K25). In this context, farmers are unwilling to invest in

traps and adopt a passive attitude, expecting the government to provide them.

Moreover, they tend to only visually assess crop damage, without conducting

actual counts that would evidence precise infestation levels. Additionally,

producers did not recognize natural enemies in the brochure (parasitoids and

predators). This result contrasts Rivero et al. (2012)

in Catamarca, where nearly one-third of the producers recognized parasitoids on

their farms.

Regarding

alternative host species, only three farmers could identify all potential hosts

of C. pomonella, and just one acknowledged the need to manage the pest

in those crops (figure 2, H20). Most producers named only one

or two hosts, primarily quince (C. oblonga), and believed that C.

pomonella affected only walnut trees. Parallel assessments conducted on the

same farms indicated that quince trees experienced an average fruit damage rate

of 7% during the 2023-2024 season, with peak damage observed in January and

February (Ing. Barros, pers. comm.). This gap between knowledge and reality may

be linked to limited training opportunities and weak communication between

farmers and agricultural institutions (figure 2, J23 and

J24). Previous studies have shown that workshops facilitated by technical

specialists can strengthen farmer networks and improve pest management outcomes

(26, 32).

These findings only

partially support our three hypotheses. Ecologically, although habitat

structure may favour biological control, actual abundance and diversity of

natural enemies seem insufficient. Economically, qualitative data suggest

moderate to high pest impact, to be confirmed through quantitative assessments.

Finally, socio-culturally, knowledge of the pest is not systematically applied

in management decisions. This study diagnoses key limitations in C.

pomonella control in Ambato, addressing a gap in the literature and laying

the basis for more comprehensive, sustainable pest management in smallholder

walnut systems.

Sustainability

The average General

Sustainability Index (ISg) across the evaluated farms was 1.521, under the

established threshold value of 2.0. C. pomonella management exhibited

the highest relative sustainability in the ecological dimension (1.663),

followed by the sociocultural (1.571) and economic (1.329) dimensions (table 3).

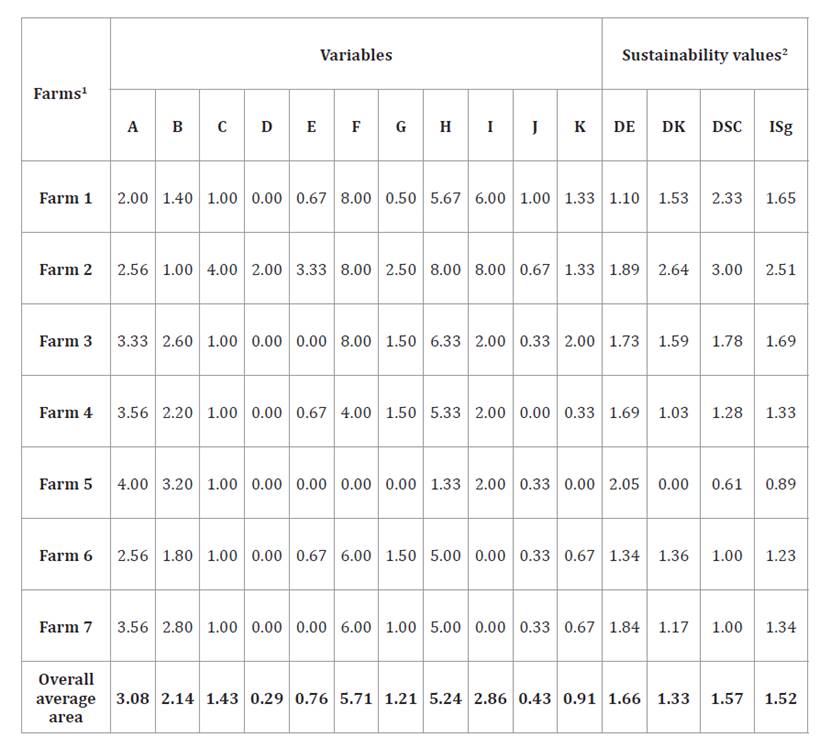

Table 3. Indicator

values in seven walnut farms in Ambato, Argentina, and general sustainability

conditions.

Tabla

3. Valores de los indicadores empleados en siete fincas

de Nogales, Ambato, Argentina y condiciones de sustentabilidad general.

1.

Walnut farms. A. On-farm diversity management. B. Spontaneous vegetation on

farm edges. C. Monitoring and regulation of C. pomonella. D. Economic

investment in C. pomonella regulation. E. Chemical control of C.

pomonella. F. Economic losses caused by C. pomonella. G. Production

marketing. H. Extent of farmer knowledge on C. pomonella, alternative

hosts and their regulation. I. Degree of knowledge of agrochemicals for the

control of C. pomonella. J. Social role of the farmer concerning C.

pomonella management. k. Extent of farmer knowledge on ecosystem services

for natural biological control of C. pomonella. 2. Results are averages

of the indicators constituting each variable. DE=Ecological Dimension. DK:

Economic Dimension. DSC: Socio-Cultural Dimension. ISg: General Sustainability

Index. Formula. Supplementary

material 1.

1.

Fincas de nogales. A. Manejo de la diversidad en la finca. B. Vegetación

espontánea en los bordes de la finca C. Monitoreo y regulación de C.

pomonella. D. Inversión económica en la regulación de C. pomonella E.

Control químico de C. pomonella. F. Pérdidas económicas causadas por C.

pomonella G. Comercialización de la producción. H. Grado de conocimiento de

los agricultores sobre C. pomonella, hospedantes alternativos y su

regulación. I. Grado de conocimiento de los agroquímicos para el control de C.

pomonella. J. Rol social del agricultor en relación con el manejo de C.

pomonella. k. Grado de conocimiento de los agricultores sobre los servicios

ecosistémicos para el control biológico natural de C. pomonella. 2. Los

resultados son el promedio de los indicadores que conforman la variable.

DE=Dimensión Ecológica. DK: Dimensión económica. DSC: Dimensión Sociocultural.

ISg: Índice de Sustentabilidad General. Fórmula. Material

suplementario 1.

These findings

underscore the multifaceted nature of sustainability in pest management. As

expected, farms relying exclusively on chemical control did not achieve the

highest sustainability scores. In several cases, farms without control

practices demonstrated comparable or even higher sustainability indices. This

counterintuitive outcome can be attributed to absent monitoring practices

across farms, regardless of management intensity. Control measurements without

monitoring, particularly chemical applications, are often untimely, excessive,

ineffective and economic-ecologically expensive. The absence of integrated

monitoring systems constitutes a critical barrier for sustainable pest control.

Cluster

Analysis

Cluster analysis based on the General Sustainability Index (ISg)

identified four distinct groups of farms reflecting sustainability degrees (table 3). Cluster One with the highest sustainability level,

comprised only Farm 2, with an ISg of 2.509, surpassing the threshold of 2.0.

However, closer examination revealed that this value was driven by higher

economic and sociocultural scores, while ecological performance remained

limited. The producer demonstrated knowledge of C. pomonella management,

including alternative hosts and appropriate agrochemical use. Ecological

indicators on this farm revealed sparse vegetation cover, greater distances to

spontaneous vegetation, and limited floral diversity from ecologically relevant

plant families. At the opposite end, Cluster Two was represented by Farm 5,

with the lowest sustainability score (ISg: 0.887). Unlike the other units, this

farm’s primary activity is livestock production, with walnut cultivation

playing a minor role. Consequently, C. pomonella was not perceived as a

significant threat, and no management strategies were implemented. Between

these extremes, cluster Three included Farms 4, 6, and 7 (ISg: 1.331, 1.233,

and 1.335, respectively), and Cluster Four included Farms 1 and 3 (ISg: 1.654

and 1.698, respectively). These clusters differed primarily in their ecological

characteristics. Farms in Cluster Four exhibited higher vegetation cover and

greater plant diversity, including flowering species and fruit crops,

supporting beneficial arthropod communities. These farmers also reported

greater economic losses due to C. pomonella, indicating pest pressure

and greater economic dependency on walnut production.

Conclusion

This study

represents the first assessment of sustainability gaps in the phytosanitary

management of C. pomonella among smallholder walnut farmers in

Argentina. The findings highlight that effective and sustainable pest control

must encompass ecological, economic, and sociocultural dimensions, rather than

single-point interventions. To initiate meaningful changes, participatory

frameworks must engage all relevant stakeholders, including farmers, academic

researchers, and public institutions involved in agricultural policy and

extension services. These workshops should be collaborative spaces for

knowledge exchange, trust-building, and context-appropriate co-design

management strategies. Key prevention must implement systematic pest monitoring

and promote ecological practices aimed at regenerating native vegetation and

enhancing habitats for natural enemies. Such efforts would strengthen ecosystem

resilience and support reestablishing natural biological control mechanisms for

C. pomonella. In parallel, enhancing market strategies through

value-added products (e.g., processed walnuts, specialty foods) could

improve profitability, promote investment in sustainable practices, and

increase resilience of walnut production systems. Ultimately, sustainability in

smallholder agricultural systems depends on technical improvements in pest

control and integration of holistic strategies that align ecological integrity

with economic viability and social inclusion. Without adequate profitability,

the relative importance of ecological and social factors diminishes, weakening

long-term sustainability. Addressing vulnerabilities across all sustainability

dimensions (not just one) is essential for effective management of C.

pomonella and secure regional walnut production.

Acknowledgments

We thank the walnut

farmers of Ambato for granting access to their farms and participating in the

interviews. We thank Gabriel Reinoso Franchino for assistance in plant species

identification, Miguel A. Garlati for general assistance, and Nahuel V. Morales

Castilla and Marcos S. Macchioli Grande for language contributions.

This article was proofread by Servicio de Ediciones Científicas

de la FCA, UNCuyo, Mendoza.

1.

Abraham, L.; Alturria, L.; Fonzar, A.; Ceresa, A.; Arnés, E. 2014. Propuesta de

indicadores de sustentabilidad para la producción de vid en Mendoza, Argentina.

Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 46(1): 161-180.

2.

Altieri, M. A.; Nicholls, C. I. 2007. Biodiversidad y manejo de plagas en

agroecosistemas (Vol. 2). Icaria editorial.

3.

Astier M.; López Ridaura, S.; Pérez E.; Masera O. R. 2002. El Marco de

Evaluación de Sistemas de Manejo incorporando Indicadores de Sustentabilidad

(MESMIS) y su aplicación en un sistema agrícola campesino en la región

Purhepecha, México. Agroecología. 415-430.

4.

Aubel, A. J. 2022. Estudios de nuevas herramientas de control de plagas de

nogales con énfasis en Cydia pomonella en el Valle Inferior del Río

Negro. Primera experiencia. Tesis final de Carrera en Ingeniería Agronómica,

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Río Negro. Argentina.

5.

Barros, L. A.; Espinosa, M.; Romero, O. E.; Carrizo, A.; Cavallo, M. J.; Diez,

P. A. 2024. Actualización sobre la presencia natural de Goniozus legneri (Hymenoptera:

Bethylidae) en agroecosistemas nogaleros de Catamarca y primer registro en el

Departamento Famatina, Provincia de La Rioja. Revista de la Sociedad

Entomológica Argentina. 83(3). DOI: 10.25085/rsea.830305.

6.

Belles, C.; Cichón, L.; Di Masi, S.; Fernández, D.; Magdalena, C.; Rial, E.;

Rossini M. 1996. Guía de pulverizaciones. 72 p.

7.

Blomefield, T. 1994. Codling moth resistance. It is here, and how do we manage

it? Deciduous Fruit Grower. 44(4): 130-132.

8.

Carrizo, A.; Carrasco, F.; Aybar, S.; Leiva, S.; Matías, A. 2015. Estimación

del Coeficiente de Impacto Ambiental (EIQ) en diferentes estrategias

fitosanitarias en sistemas de pequeños productores de nogal, como una herramienta

hacia la transición agroecológica en Catamarca, Argentina. V Congreso

Latinoamericano de Agroecología-SOCLA, La Plata.

9.

Casado, G. G.; Mielgo, A. A. 2007. La investigación participativa en

agroecología: una herramienta para el desarrollo sustentable. Ecosistemas.

16(1).

10.

Cavallo, M. J.; Romero, O. E.; Barros, L. A.; Cichón, L.; Garrido, S. A.; Diez,

P. A. 2024. Functional and numerical response and mutual interference of Goniozus

legneri (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae) on Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera:

Tortricidae): Its implications for biological control. Journal of Applied

Entomology. 148(4): 454-463. https://doi.org/10.1111/ jen.13238

11.

Censo República Argentina. 2022. Resultados del Censo 2022-Catamarca. https://

censo.gob.ar/ index.php/datos_definitivos_catamarca (Fecha de consulta:

27/11/2024).

12.

Cichón L.; Fernández D. E. 1995. TRV Aplicación de volúmenes adecuados en

cultivos de frutales de pepita. Ed. EEA Alto Valle.

13.

Cichón, L.; Di Masi, S.; Fernández, D.; Magdalena, C.; Rial, E.; Rossini, M.

1996. Guía ilustrada para el monitoreo de plagas y enfermedades en frutales de

pepita. Ed. INTA Centro Regional Patagonia Norte. 72 p.

14.

Cichón L.; Fernández D. E.; Montagna, M. 2015. Evolución del control de

carpocapsa en los últimos veinticinco años. Rev. Fruticultura y

Diversificación. 51: 22-29.

15.

Daly H. E 1997. De la economía del mundo lleno a la economía del mundo vacío.

Ed. Goodland, R. et al. Medio ambiente y desarrollo sostenible. 35-50 p.

16.

Errecart, V. 2012. Diagnóstico de la cadena de la nuez de nogal de las

provincias de La Rioja y Catamarca. Estrategias y tácticas para mejorar su

inserción en el comercio internacional. Tesis de grado de Magister, área

Agronegocios y Alimentos. Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires. Argentina.

17.

Ferrero A.; Laumann R.; Gutierrez M. M.; Stadler T. 2000. Evaluación en

laboratorio de la toxicidad de insecticidas en Cydia pomonella L.

(Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) y en su enemigo natural Goniozus legneri

Gordh (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae). Publicación de la Agricultura, Rev. de Sanidad Vegetal. Plagas. 26(4): 559-575.

18.

Garrido S.; Cichón L.; Fernández D.; Azevedo C. 2005. Primera cita de la

especie Goniozus legneri (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae) en el Alto Valle de

Río Negro, Patagonia Argentina. Rev. Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. 64(1-2):

14-16.

19.

Gould, F.; Brown, Z. S.; Kuzma, J. 2018. Wicked evolution: Can we address the

sociobiological dilemma of pesticide resistance? Science. 360(6390): 728-732.

DOI: 10.1126/science. aar378

20.

Guzmán Casado G. M.; González de Molina N.; Sevilla Guzmán E. 2000. Métodos y

técnicas en Agroecología, Introducción a la agroecología como desarrollo rural

sostenible. 5: 149-195.

21.

Harte, M. J. 1995. Ecology, sustainability, and environment as capital.

Ecological Economics. 15: 157-164.

22.

Huerga, M.; San Juan, S. 2005. El control de las plagas en la agricultura

argentina. Estudio Sectorial Agrícola Rural-Banco Mundial/Centro de Inversiones

FAO-Buenos Aires, Argentina.

23.

Iermanó, M. J.; Sarandón, S. J.; Tamagno, L. N.; Maggio, A. D. 2015. Evaluación

de la agrobiodiversidad funcional como indicador del potencial de regulación

biótica. Aroecosistemas del sudeste bonaerense. Rev. Facultad de Agronomía. La

Plata. 114(3): 1-14.

24.

Juri, C.; Zárate, L. 2017. Evaluación de la sustentabilidad de una finca

nogalera de un pequeño productor en Mutquin - Pomán - Catamarca. Rev.

Divulgación Técnica Agrícola y Agroindustrial, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias -

UNCa. 69.

25.

Keil S.; Gu H.; Dorn S. 2001. Response of Cydia pomonella to selection

on mobility: laboratory evaluation and field verification. Ecological

Entomology. 26(5): 495-501. https://doi. org/10.1046/j.1365-2311.2001.00346.x

26.

Landini, F. 2022. Intercambio de experiencias y aprendizaje horizontal entre

extensionistas: Fuente invisibilizada de conocimientos para la práctica.

Psicoperspectivas. 21(3): 7-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.5027/

27.

Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. 2008. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate

analysis. Journal of statistical software. 25: 1-18.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01

28.

Leyton, J. F. 2023. Efectos subletales de agroquímicos sintéticos y naturales

contra Goniozus legneri Gordh (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae). Tesis de

Magíster en Ciencias Agronómicas. Universidad de Concepción, Chile.

29.

López, I.; Lovi, A.; Trejo, J. 2014. Análisis del agregado de valor en la

cadena agroalimentaria de la nuez de nogal: caso Establecimiento Finca Don

Manuel, Chilecito-La Rioja. Trabajo Final - Áreas de Consolidación, Ingeniería

Agronómica. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina.

30.

Manetti, A.; Lara-Navarra, P.; Sánchez-Navarro, J. 2022. El proceso de diseño

para generación de escenarios futuros educativos. Rev. científica

iberoamericana de comunicación y educación. 30 (73). DOI: 10.3916/C73-2022-03

31.

Marcucci, B.; Mazzitelli, M. E.; Garrido, S. A.; Cichón, L. I.; Becerra, V. C.;

Luna, M. G. 2023. Presencia de Goniozus legneri (Hymenoptera:

Bethylidae) y su asociación con lepidópteros plagas en el oasis cultivado Norte

de la provincia de Mendoza, Argentina. Rev. Sociedad Entomológica Argentina.

82(2): 5-5.

32.

Maschio, J. I. 2017. Caracterización de los productores de nogal y su relación

con la calidad final del producto en la provincia de Catamarca. Cartilla de

divulgación técnica. Revista de Divulgación Técnica Agrícola y Agroindustrial.

76.

33.

Matteucci, S. D.; Colma, A. 1982. Metodología para el estudio de la vegetación.

Programa Regional de Desarrollo, Científico y Tecnológico. 22.

34.

Nicholls, C. 2006. Bases agroecológicas para diseñar e implementar una

estrategia de manejo de hábitat para control biológico de plagas. Agroecología.

1: 37-48.

35.

Nicholls, C. I. 2008. Control biológico de insectos: un enfoque agroecológico.

Ed. Universidad de Antioquia. 282 p.

36.

Nievas, W. E.; Rossini, M. N.; Toranzo, J. O.; Iannamico, L. A.; Magdalena, J.

C.; Fernandez, D. E.; Curetti, M. 2014. Bacteriosis del nogal (Xanthomonas

campestris pv. juglandis) en el Valle Medio del río Negro. Repositorio EEA

Alto Valle, INTA. https://repositorio.inta. gob.ar/

bitstream/handle/20.500.12123/16962/INTA_CRPatagoniaNorte_EEAAltoValle_ Nievas_

WE_Bacteriosis_nogal_Xanthomonas_campestris_pv_juglandis.pdf?sequence=1 (fecha

de consulta:20/11/2024).

37.

Obschatko, E. 2009. Las explotaciones agropecuarias familiares en la República

Argentina. Un análisis a partir de los datos del Censo Nacional Agropecuario

2002. Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentos. 68.

http://repositorio.iica.int/handle/11324/6860

38.

Pearce, D.; Atkinson, G. 1993. Capital theory and measure-ments of sustainable

development: an indicator of weak sustainability. Ecological Economics. 8(2):

103-108.

39.

Prataviera, A. G. 2000. Problemática del cultivo de la nuez de nogal en las

provincias de Catamarca y La Rioja. INTA, Estación Experimental Agropecuaria

Catamarca. Informe 4.

40.

Quintana, G.; Cólica, J.; Fernández Gorgola, M.; Rivero, C.; Pérez, O.; Luna

Mercado L. 2007. Control de Carpocapsa (Cydia pomonella L.) con un

producto en base al virus de la granulosis (CPGV), en cultivos de nogal en

Catamarca. Rev. CIZAS. 8: 39-48.

41.

Quintana, G; Cólica J. 2011. Carpocapsa: plaga clave en nogal. Aspectos

morfológicos y biológicos relevantes para un control adecuado. Informe Técnico

INTA. 1.

42.

Rivero, C.; Cólica, J.; Fernández, G. M.; Cruz, R.; Luna, M.; Rivero, A. R.

2012. El nogal: situación productiva en la localidad de El Potrero, Andalgalá,

Catamarca. Rev. CIZAS. 22.

43.

Sarandón, S. J. 2002. El desarrollo y uso de indicadores para evaluar la

sustentabilidad de los agroecosistemas. Agroecología. 20: 393-414.

44.

Sarandón, S. J.; Zuluaga, M. S.; Cieza, R.; Janjetic, L.; Negrete, E. 2006.

Evaluación de la sustentabilidad de sistemas agrícolas de fincas en Misiones,

Argentina, mediante el uso de indicadores. Agroecología. 1: 19-28.

45.

Sarandón, S. J.; Flores, C. C. 2009. Evaluación de la sustentabilidad en

agroecosistemas: una propuesta metodológica. Agroecología. 4: 19-28.

46.

Sazo, L.; Araya, J. E.; Rodríguez, P. 2006. Evaluación de la susceptibilidad de

Cydia pomonella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) al azinfosmetil en

Chile. Boletín Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa. 39: 451-453.

47.

Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentos (SAGPyA). 2024. Informe

síntesis de la economía regional: nuez del nogal. https://alimentosargentinos.magyp.gob.ar/

HomeAlimentos/

economias-regionales/producciones-regionales/informes/Informe_Nuez_nogal.pdf/

(fecha de consulta 27/12/2024).

48.

Soleño J.; Anguiano O. L.; Cichón L. B.; Garrido S. A.; Montagna; C. M. 2012.

Geographic variability in response to azinphos-methyl in field-collected

populations of Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) from

Argentina. Pest Management Science. 68(11): 1451-1457.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.3327

49.

Tamagno, L. N.; Iermanó, M. J.; Sarandón, S. J.; Pérez, R. A. 2014. Influencia

de los saberes de los agricultores familiares pampeanos sobre las decisiones

productivas y tecnológicas: su relación con un manejo sustentable. Acta IX

Congreso Latinoamericano de Sociología Rural. México.

50.

Wezel, A.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; Bezner-Kerr, R.; Barrios, E.; Rodrigues

Gonçalves, A.; Sinclair, F. 2020. Agroecological principles and elements and

their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review.

Agronomy for Sustainable

Development. 40: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-020-00646-z /

Supplemmentary

material:

Funding information

The study was funded by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción

Científica y Tecnológica de Argentina through “Fondo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología

(FONCyT)” (PICT 2018-02508, PICT 2020-03499 and PICT 2021-00194) and “Fondos

Complementarios para proyectos de Investigación con el Impacto en el territorio

Argentino 2024 - Fundación Williams”.