Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

The Native Dryland PGPR ‘Pseudomonas

42P4’ Promotes Adventitious Rooting in Woody Cuttings of Vitis spp.

La

PGPR nativa de zonas áridas ‘Pseudomonas 42P4’ promueve la fomación de

raíces adventicias en estacas leñosas de Vitis spp.

Maria Gabriela

Gordillo1,

Fanny Colombo3,

1Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Instituto de Biología Agrícola de Mendoza (IBAM-CONICET). Almirante Brown 500.

Chacras de Coria. M5528AHB. Mendoza. Argentina.

2Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Almirante Brown 500. Chacras de Coria. M5528AHB. Mendoza. Argentina.

3Trapiche Winery. Calle Nueva Mayorga s/n. Maipú. Mendoza.

Argentina. CPA: M5513

*cgonzalez@fca.uncu.edu.ar

Abstract

This study

evaluated the effect of two native PGPR strains from an arid region (Mendoza,

Argentina) on the rooting of woody cuttings of Vitis spp. These strains

are known for their growth-promoting capacity, including auxin production.

Dormant V. vinifera cv. Malbec cuttings were grafted onto four

rootstocks - 1103 Paulsen, 110 Richter, 101-14 MGt and SO4. Then, basal ends of

these grafted cuttings and own rooted controls were incubated for 12 h in

solutions of (1) Pseudomonas 42P4 at 107 CFU mL-1,

(2) Enterobacter 64S1 at 107 CFU mL-1,

(3) autoclaved LB medium, (4) water, and (5) a quick-dip immersion of

Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). After treatment, the cuttings were placed in a

forcing chamber at 28°C and relative humidity ~100% for 21 days. Rooting

parameters and scion-rootstock union percentages were recorded. Pseudomonas 42P4

significantly promoted rooting in Malbec own-rooted cuttings. However, Enterobacter

64S1 had negative or null effects. Furthermore, Pseudomonas 42P4

enhanced rooting in Malbec grafted onto 1103 Paulsen, but not on 101-14 MGt,

110 Richter or SO4. This strain also improved graft union success on SO4, but

did not affect the other rootstocks. These results suggest that a dryland

native strain such as Pseudomonas 42P4 could sustainably enhance the quality of

both own-rooted and grafted grapevine plants in commercial nurseries.

Keywords: PGPR, grapevine

rootstock, Malbec, rooting, graft union, nursery

Resumen

El objetivo de este

estudio fue evaluar el efecto de dos cepas PGPR nativas de zonas áridas

(Mendoza, Argentina) con capacidad promotora del crecimiento (que producen

auxinas) sobre el enraizamiento de estacas leñosas de Vitis spp. La base

de las estacas de Vitis vinifera cv. Malbec, tanto francas como

injertadas sobre cuatro portainjertos:1103 Paulsen, 110 Richter, 101-14 MGt y

SO4, se incubaron durante 12 h en soluciones de 1) Pseudomonas 42P4 y 2)

Enterobacter 64S1 107 UFC mL-1,

3) medio LB autoclavado, 4) agua y 5) una inmersión rápida de ácido

indol-3-butírico (IBA). Posteriormente, las estacas se colocaron en una cámara

de forzadura a 28°C y humedad relativa ~100% durante 21 d. Se midieron

diferentes parámetros de enraizamiento y el porcentaje de unión del injerto.

Los resultados mostraron que Pseudomonas 42P4, pero no Enterobacter 64S1

promovió el enraizamiento, de forma similar a IBA en estacas de Malbec. La cepa

Pseudomonas 42P4 también promovió el enraizamiento de estacas injertadas

sobre 1103 Paulsen, pero no sobre 101-14, 110 Richter y SO4. Además, Pseudomonas

promovió la unión del injerto en SO4, pero no en 110 Richter, 1103 Paulsen

y 101-14. Estos resultados sugieren que una cepa nativa de zonas áridas podría

utilizarse como una herramienta sustentable para mejorar la calidad de plantas

francas e injertadas de vid.

Palabras clave: PGPR, portainjertos

de vid, Malbec, enraizamiento, unión del injerto, vivero

Originales: Recepción: 16/04/2025

- Aceptación: 06/07/2025

Introduction

A significant

portion of worldwide agricultural land (45%) is dryland. Climate change (CC)

threatens agroecosystems, causing detrimental effects on crop productivity (Berdugo

et al., 2020; Burrel et al., 2020). Viticulture

covers 7.3 million hectares of the world, with over 60% of grapes produced in

drylands (OIV

2023; Flexas et al., 2010). Argentina ranks seventh, with the largest cultivated vineyard

area globally. This country mainly develops irrigated viticulture in drylands (OIV

2023, INV 2023).

Grapevines are

clonally propagated through one-year woody cuttings. Grafted or ungrafted woody

cuttings are forced under high relative humidity (RH) and ± 27°C to stimulate

adventitious root formation and scion-rootstock healing (in grafted plants).

External factors (temperature, humidity, substrate aeration) and internal

factors (carbohydrate reserves, hormones, and genotype) influence these processes

(Hartmann

et al., 2014).

Rootstocks exhibit

resistance to pathogens and diseases, and confer tolerance to abiotic stresses

(Hartmann

et al., 2014; Ollat et al., 2016, Keller, 2020, D’Innocenzo et

al., 2024). V. vinifera cultivars are generally grafted onto

American Vitis spp. hybrid rootstocks due to

their resistance to phylloxera (Mudge et al., 2009). Grafting is

essential in most European wine-growing regions. However, outside Europe,

vineyards can be planted with own-rooted V. vinifera plants.

One main problem in

grapevine propagation is the differential rooting capacity of rootstocks.

Rootstocks 110 Richter (110 R) and Selection Oppenheim 4 (SO4) are recalcitrant

to form adventitious roots. This differs from other widely used grapevine

rootstocks like 1103 Paulsen (1103 P) and 101-14 Millardet et de Grasset

(101-14 MGt), which induce more root development (Keller, 2020). Low rooting

capacity causes significant economic losses to nurseries. Additionally,

scion-rootstock interaction plays a crucial role in rooting. The scion may

affect root dry weight per woody cutting (Tandonnet et al., 2009), as the

scion-rootstock union simultaneously occurs with rooting, depending on cutting

reserves.

Auxins are the main phytohormones in adventitious root

production of woody cuttings (Burnoni et al.,

2022), though their effect varies among genotypes. For example,

indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), a primary synthetic auxin used for grapevine

rooting (Machado et al., 2005),

promotes rooting in woody cutting of 110 R, SO4 and 101-14 MGt (Gordillo

et al., 2022; Satisha et al., 2008).

In contrast, IBA may promote (Satisha et

al., 2008; Daskalakis et al., 2018) or not (Boeno

et al., 2023; Gordillo et al., 2022)

rooting of 1103 P woody cuttings. However, synthetic agrochemicals are

progressively being excluded as organic and agroecological agriculture gains

attention (Centeno et al., 2008).

Plant

Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) are plant symbiotic bacteria that

colonize the rhizosphere and produce indole acetic acid (IAA)-type auxins (Glick et

al., 2012; Pantoja Guerra et al., 2023). Some PGPR

strains promote rooting of difficult-to-root rootstocks, while others have no

effect (Isçi

et al., 2019; Toffanin et al., 2016). Our group

isolated and characterized two PGPR strains from Mendoza´s arid soils of

Argentina. Pseudomonas 42P4 (42P4) and Enterobacter 64S1 (64S1)

produce IAA (Pérez-Rodríguez

et al., 2020a) and promote seedling growth of Solanum lycopersicum (Pérez-Rodríguez

et al., 2022) and Capsicum annuum seedlings (Lobato

Ureche et al., 2021), alleviate saline stress in tomato (Pérez-Rodríguez

et al., 2022), and increase drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana plants

(Jofré

et al., 2024). Furthermore, Pseudomonas 42P4 enhances tomato growth,

yield and fruit quality under field conditions (Pérez-Rodríguez et al.,

2020b).

Both strains also exhibit biocontrol activity, inhibiting tomato and pepper

crop diseases (unpublished data). Native strains easily adapt to edaphic

conditions, resist local environmental stresses, and are more successful when

inoculated into the plant rhizosphere.

PGPR improve

rooting and survival of young plants of various species. However, few studies

report PGPR´s effect on woody plant production or grapevine woody cuttings,

specifically (Bartolini

et al., 2017; Köse et al., 2003, 2005; Tofanin et al.,

2016).

Currently, exploring sustainable tools is imperative, especially given global

warming threats, particularly challenging in drylands.

Therefore, this

work evaluated the effect of two native PGPR strains from Mendoza’s arid soils,

Pseudomonas 42P4 and Enterobacter 64S1, on adventitious root

production of the Argentinean emblematic cultivar: Malbec, and the four most

widespread rootstocks in global viticulture and Argentine arid areas: SO4, 110

R, 1103 P, and 101-14 MGt (Riaz et al., 2019). These strains,

adapted to arid soils, could constitute a sustainable alternative for synthetic

agrochemicals in grapevine propagation.

Materials

and Methods

Bacterial

Culture

Pseudomonas 42P4 (42P4) and Enterobacter

64S1 (64S1) were collected, isolated and characterized by the Plant

Physiology and Microbiology Group (IBAM- FCA, CONICET-UNCuyo, Mendoza,

Argentina). The partial 16S rRNA sequence of both strains was deposited in

GenBank under accession numbers MT045993.1 and MT047267, respectively (Pérez-Rodríguez

et al., 2020a). Inocula were prepared in 1 L Erlenmeyer Flask with 400 mL of

Luria Broth (LB) culture medium (10 g Peptone, 5 g Yeast Extract, 5 g NaCl in 1

L of bidistilled H2O). Bacteria were cultured in an orbital shaker at 120

rpm and 32°C for 24 h. Strain concentration was estimated by optical density at

540 nm in a spectrophotometer according to Pérez-Rodriguez et al.

(2020a). From these cultures, a dilution to 107 colony-forming units

(CFU) mL–1 was prepared for each

strain in PBS (phosphate buffer saline).

Plant

Material, Inoculation and Rooting Conditions

Two experiments

were conducted in the grapevine nursery of Grupo Peñaflor S.A. (Trapiche

Winery), located in Santa Rosa, Mendoza, Argentina (33°15‘39.4” S 68°07’48.9”

W). The first experiment was conducted during the 2020 season

(September-October) and the second, in 2021. Cuttings (length: 40 cm and

diameter: 9 mm) were collected in winter and stored at 4°C until experiment

initiation.

In the first

experiment, we tested different doses of Pseudomonas 42P4 and Enterobacter

64S1 on the rooting capacity of V. vinifera cv. Malbec woody

cuttings. Before forcing, we applied five treatments: (1) 30-second quick

immersion in 1000 ppm IBA solution (Gordillo et al. 2022); or 12-hour

incubation in solutions of: (2) Pseudomonas 42P4 at 107 CFU mL-1,

(3) Enterobacter 64S1 at 107 CFU

mL-1, (4)

autoclaved LB, and (5) tap water (control treatment) on the base (1.5 cm) of 50

woody cuttings per treatment.

In a second

experiment, we evaluated Pseudomonas 42P4 on the rooting of Malbec

cuttings (with 2 buds and approximately 5 cm long) grafted onto cuttings of

101-14 MGt (V. riparia × V. rupestris), SO4 (V. berlandieri × V.

riparia), 1103 Paulsen, and 110 Richter (V. berlandieri × V. rupestris),

with 5 buds (approximately 35 cm long and 9 mm in diameter). We used an Omega

grafting machine (Fornasier Cesare & C., Italy). Each grafted cutting was

40 cm long. The grafting zone was covered with a commercial initiation wax

(Guerowax Crecimiento 78, Guerola Industries, Spain) to prevent dehydration and

diseases during forcing. Before forcing we applied the following treatments:

(1) a 30-second quick immersion at 750 ppm IBA (Gordillo et al. 2022), and 12-hour

incubations with: (2) Pseudomonas 42P4 at 107 CFU mL-1,

(3) autoclaved LB, and (4) tap water (control) on the base (1.5 cm) of 50

grafted cuttings per treatment.

Subsequently, in

both experiments, cuttings were horizontally placed in plastic boxes with peat

(KEKKILÄ professional, https://www.kekkilaprofessional.com/). Then, cuttings

were forced and maintained for 21 days at 28°C and 100% RH.

The experimental

design was a completely randomized design, considering each cutting as an

experimental unit.

Morphological

Parameters

Treatment effect

was evaluated by callus and rooting percentages, followed by root number and

biomass (g) per cutting. Rooting percentage is the percentage of cuttings that

produced at least one root. Callus percentage was visually determined as the

proportion of the cutting base occupied by callus (0-25, 25-50, 50-75, and

75-100%). Root biomass was determined as dry weight (DW) of all adventitious

roots from a cutting, oven-dried at 60°C to constant weight. In grafted

cuttings, the percentage of scion-rootstock union was visually determined as

well (0-25, 25-50, 50-75, and 75-100%).

Statistical

Analysis

Statistical

analyses were performed using the InfoStat P 2020v software (Di

Rienzo et al., 2020). Rooting, callus and graft union percentages, along with root

number and biomass, were analysed with Generalized Linear Models. A binomial

distribution was used for the first three parameters and the Poisson

distribution for the fourth. Root biomass was first tested for ANOVA assumptions

(using Shapiro-Wilks test for normality and Levene test for homoscedasticity).

Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments according

to the post-hoc test DGC (α = 0.05). Data visualization was conducted in R (R Core

Team, 2024) and the ggplot2 package (Wickham, 2016).

Results

Own-rooted

Malbec cuttings

Basal callus

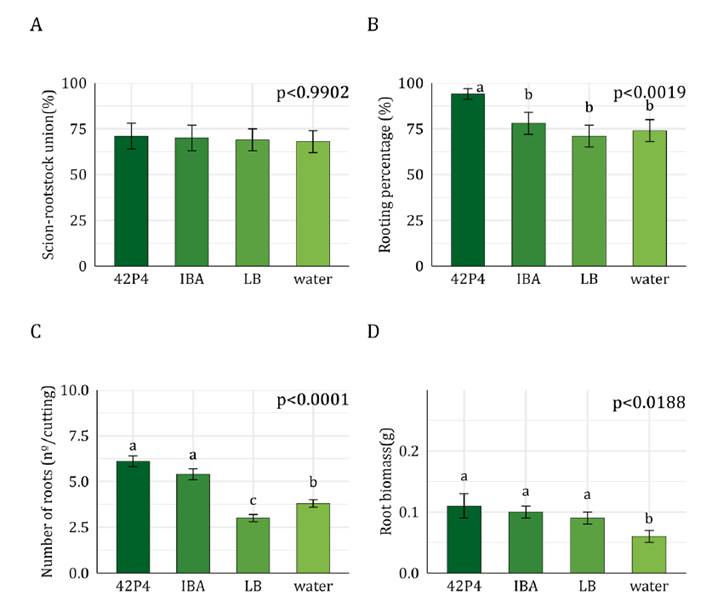

percentage on Malbec was similar among treatments (>75%, p > 0.05) (figure 1A). Pseudomonas 42P4

and IBA 1000 ppm increased rooting percentage (>80%), compared to autoclaved

LB and water treatments (70%). However, Enterobacter 64S1 decreased

rooting percentage (25%) compared to water (figure 1B). The number of

roots per cutting was similar in cuttings incubated with 42P4 and IBA (~ 6

roots per cutting), and higher than in the remaining treatments (~ 4 roots per

cutting) (figure

1C).

Root biomass per cutting was 30% higher in cuttings incubated in IBA than in

42P4. The remaining treatments yielded lower biomass (figure 1D). Pseudomonas 42P4

promoted three of the four rooting parameters compared to the water control:

rooting percentage, number of roots per cutting, and root biomass. In contrast,

the native Enterobacter 64S1 strain did not promote any evaluated

parameter.

Based on these results, we assessed the ability of the native Pseudomonas

42P4 strain (but not Enterobacter) to promote rooting and graft

union of Malbec cuttings grafted onto four grapevine rootstocks.

A)

Callus percentage, B) Rooting percentage, C) Number of roots per cutting, and

D) Root biomass per cutting.

Values

correspond to adjusted means ± SEM (n=50). Data were analysed with General or

Generalized Mixed Linear Models. Different letters indicate significant

differences among treatments according to the post-hoc test DGC (α = 0.05).

42P4:

Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter 64S1, IBA: Indole-3-butyric

acid, LB: Luria Broth culture medium, water: tap water.

A)

Porcentaje de callo, B) Porcentaje de enraizamiento, C) Número de raíces por

estaca y D) Biomasa de raíces por estaca.

Los

valores corresponden a las medias ajustadas ± EE (n=50). Los datos fueron

analizados mediante Modelos Lineales Mixtos Generales o Generalizados. Letras

diferentes indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos según el test

post-hoc DGC (α = 0,05).

42P4: Pseudomonas

42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter 64S1, IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, LB:

medio de cultivo Luria Broth, water: agua de red.

Figure

1. Own-rooted Malbec cuttings.

Figura 1. Estacas

de Malbec a pie franco.

Grafted

Cuttings

1103 Paulsen

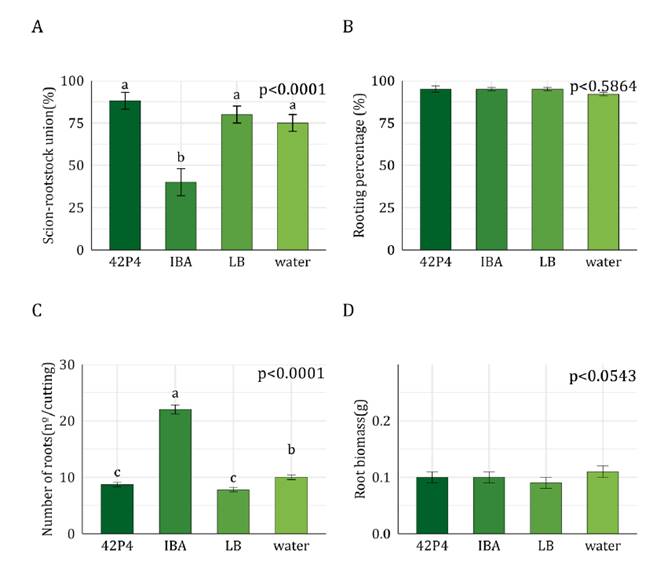

The graft union percentage (~75%) between Malbec and 1103 P

rootstock, and callus percentage (~100%, p > 0.05, data not shown) were

unaffected by treatments (figure 2A).

Rooting percentage was higher (~90%) in cuttings incubated with Pseudomonas 42P4

(figure

2B) than in other treatments (~75%). The number of roots per cutting

was duplicated in 42P4 and IBA treatments than in the controls (water and LB) (figure

2C). However, root biomass was 10% higher in cuttings incubated

with 42P4 and IBA compared to the other treatments (figure 2D).

Pseudomonas 42P4 promoted a 15% increase in rooting percentage compared

to IBA, while matching root number and biomass results to this hormone

treatment.

A)

Scion-rootstock union percentage, B) Rooting percentage, C) Number of roots per

cutting, and D) Root biomass per cutting. Values correspond to adjusted means ±

SEM (n=50). Data were analysed with General or Generalized Linear Models.

Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments according

to the post-hoc test DGC (α = 0.05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter

64S1, IBA: Indole-3-butyric acid, LB: Luria Broth culture medium, water:

tap water.

A) Porcentaje de

unión entre la púa y el portainjerto, B) Porcentaje de enraizamiento, C) Número

de raíces por estaca y D) Biomasa de raíces por estaca. Los valores

corresponden a las medias ajustadas ± EE (n=50). Los datos fueron analizados

mediante Modelos Lineales Mixtos Generales o Generalizados. Letras diferentes

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos según el test post-hoc

DGC (α = 0,05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter 64S1,

IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, LB: medio de cultivo Luria Broth, water: agua de

red.

Figure

2. Rootstock 1103 Paulsen.

Figura 2. Portainjerto

1103 Paulsen.

101-14 MGt

The scion-rootstock union percentage between Malbec and 101-14

MGt rootstock decreased by 25% when cuttings were incubated with IBA compared

to the other treatments (figure 3A).

Callus percentage (~100%, p>0.05) (data not shown), rooting percentage

(~100%), and root biomass of 101-14 MGt were not affected by the treatments (figure

3B and 3D). The IBA treatment increased the number of roots per cutting

(20 roots per cutting) compared to the water control (10 roots per cutting) (figure

3C), while 42P4 and LB treatments decreased this variable to 7

roots per cutting compared to the water control. Inoculation of 101-14

rootstock cuttings with the 42P4 native strain did not promote rooting or graft

union.

A)

Scion-rootstock union percentage, B) Rooting percentage, C) Number of roots per

cutting, and D) Root biomass per cutting. Values correspond to adjusted means ±

SEM (n=50). Data were analyzed with General or Generalized Linear Models.

Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments according

to the post-hoc test DGC (α = 0.05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter

64S1, IBA: Indole-3-butyric acid, LB: Luria Broth culture medium, water:

tap water.

A) Porcentaje de

unión entre la púa y el portainjerto, B) Porcentaje de enraizamiento, C) Número

de raíces por estaca y D) Biomasa de raíces por estaca. Los valores

corresponden a las medias ajustadas ± EE (n=50). Los datos fueron analizados

mediante Modelos Lineales Mixtos Generales o Generalizados. Letras diferentes

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos según el test post-hoc

DGC (α = 0,05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter 64S1,

IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, LB: medio de cultivo Luria Broth, water: agua de

red.

Figure

3. Rootstock 101-14 MGt.

Figura 3. Portainjerto

101-14 MGt.

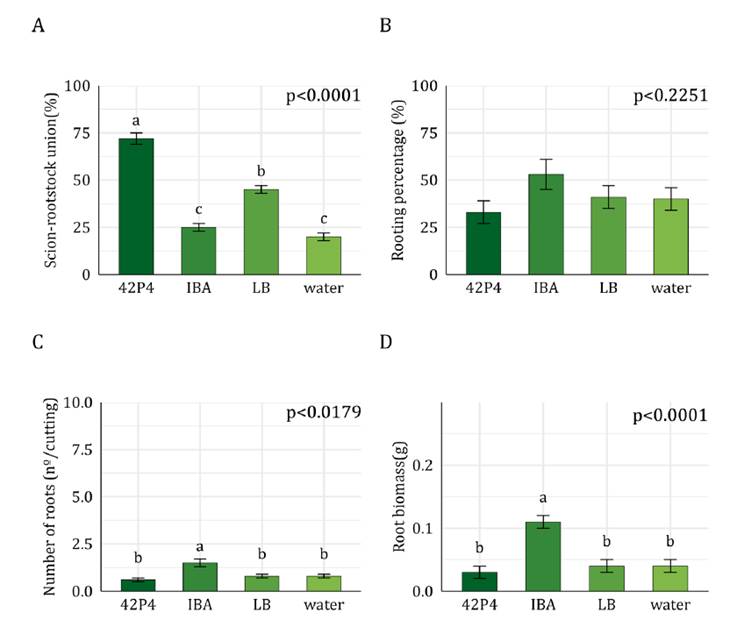

110 Richter

Graft union percentage between Malbec and 110 R rootstock was

higher in autoclaved LB compared to the other treatments (figure 4A).

However, callus percentage (~100%, p > 0.05, data not shown), rooting

percentage (~75%), and root biomass per cutting were similar among treatments (figure

4B and 4D). Root number per cutting was higher in cuttings incubated with

IBA (4 roots per cutting) than in other treatments (2.5 roots per cutting) (figure

4C). Pseudomonas 42P4 did not promote rooting or graft

union of 110 R.

A)

Scion-rootstock union percentage, B) Rooting percentage, C) Number of roots per

cutting, and D) Root biomass per cutting. Values correspond to adjusted means ±

SEM, n=50. Data were analysed with General or Generalized Linear Models.

Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments according

to the post-hoc test DGC (α = 0.05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter

64S1, IBA: Indole-3-butyric acid, LB: Luria Broth culture medium, water:

tap water.

A) Porcentaje de

unión entre la púa y el portainjerto, B) Porcentaje de enraizamiento, C) Número

de raíces por estaca y D) Biomasa de raíces por estaca. Los valores

corresponden a las medias ajustadas ± EE (n=50). Los datos fueron analizados

mediante Modelos Lineales Mixtos Generales o Generalizados. Letras diferentes

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos según el test post-hoc

DGC (α = 0,05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter 64S1,

IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, LB: medio de cultivo Luria Broth, water: agua de

red.

Figure

4. Rootstock 110 Richter.

Figura 4. Portainjerto

110 Richter.

SO4

Union percentage between Malbec and SO4 was higher in cuttings

incubated with 42P4 compared to the other treatments (50% higher than IBA and water,

and 25% higher than the LB treatment) (figure 5A).

Callus percentage (~80%, p>0.05) and rooting percentage (40%) of the SO4

rootstock were similar among treatments (figure 5B).

Root number and biomass per cutting were higher in cuttings incubated with IBA

than in other treatments (figure 5C and 5D).

Pseudomonas 42P4 did not promote rooting but increased scion-rootstock

union percentages.

A)

Scion-rootstock union percentage, B) Rooting percentage, C) Number of roots per

cutting, and D) Root biomass per cutting. Values correspond to adjusted means ±

SEM (n=50). Data were analysed with General or Generalized Linear Models.

Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments according

to the post-hoc test DGC (α = 0.05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter

64S1, IBA: Indole-3-butyric acid, LB: Luria Broth culture medium, water:

tap water.

A) Porcentaje de

unión entre la púa y el portainjerto, B) Porcentaje de enraizamiento, C) Número

de raíces por estaca y D) Biomasa de raíces por estaca. Los valores

corresponden a las medias ajustadas ± EE (n=50). Los datos fueron analizados

mediante Modelos Lineales Mixtos Generales o Generalizados. Letras diferentes

indican diferencias significativas entre tratamientos según el test post-hoc

DGC (α = 0,05). 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter 64S1,

IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, LB: medio de cultivo Luria Broth, water: agua de

red.

Figure

5. Rootstock SO4.

Figura 5. Portainjerto

SO4.

Discussion

This study is the

first to report applications of native PGPR strains from drylands in grapevine

propagation. We found that a Pseudomonas PGPR can improve rooting in

vine woody cuttings. We evaluated the ability of two native PGPR from arid

zones, Pseudomonas 42P4 and Enterobacter 64S1, to stimulate

rooting of ungrafted and grafted Vitis woody cuttings. Concerning

Malbec’s rooting, Pseudomonas 42P4 improved rooting compared to the

control, matching IBA results (figure 1, and figure

6).

Chart

sectors show the evaluated variables: rooting percentage, number of roots, and

root biomass per cutting. Green indicates significant promotion of the

parameter compared to the water control. Red indicates lower values, and yellow

indicates no significant differences among means. 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4,

64S1: Enterobacter 64S1, IBA: indole-3-butiric acid, water: tap water.

Los

sectores del gráfico muestran las variables evaluadas: porcentaje de

enraizamiento, número de raíces y biomasa de raíces por estaca. El color verde

indica que el tratamiento promovió significativamente el parámetro en

comparación con el control con agua; el color rojo indica una disminución en

los valores observados, y el color amarillo indica que no hubo diferencias

significativas entre las medias. 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, 64S1: Enterobacter

64S1, IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, wáter: agua de red.

Figure

6. Malbec. Coloured rings represent the treatments

(water, IBA, 42P4, and 64S1).

Figura

6. Malbec. El gráfico representa a los

tratamientos (agua, IBA, 42P4 y 64S1) como anillos.

Conversely, Enterobacter

64S1 failed to promote rooting of Malbec cuttings. Concerning grafted

material, Pseudomonas 42P4’s promoted rooting and graft union in a

rootstock-dependent fashion, enhancing rooting in 1103 Paulsen, but not

affecting the other rootstocks (figure 2, figure

3,

figure

4,

figure

5

and figure

7).

Optimal auxin concentrations stimulate adventitious rooting,

while higher concentrations are inhibitory (Garay-Arroyo et

al., 2014). The root-promoting effect of Pseudomonas 42P4 on

Malbec own-rooted woody cuttings could be attributed to IAA production by this

bacterium (Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2020a).

Each

chart represents a treatment (water, IBA, 42P4) as rings. Chart sectors show

the evaluated variables rooting percentage, number of roots, and root biomass

per cutting. Green indicates significant promotion of the parameter compared to

the water treatment; red indicates lower values, and yellow indicates no

significant differences among means. 42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, IBA:

indole-3-butiric acid, water: tap water.

Cada gráfico

representa los tratamientos (agua, IBA, 42P4) como anillos. Los sectores del gráfico

muestran las variables evaluadas: porcentaje de enraizamiento, número de raíces

y biomasa de raíces por estaca. El color verde indica que el tratamiento

promovió significativamente el parámetro en comparación con el tratamiento con

agua; el color rojo indica una disminución en los valores observados, y el

color amarillo indica que no hubo diferencias significativas entre las medias.

42P4: Pseudomonas 42P4, IBA: ácido indol-3-butírico, wáter: agua de red.

Figure

7. Rootstocks A) 1103 Paulsen, B) 101-14 MGt, C) 110

Richter and D) SO4.

Figura 7. Portainjertos

A) 1103 Paulsen, B) 101-14 MGt, C) 110 Richter y D) SO4.

However, as Enterobacter

produces an in vitro higher concentration of auxins than Pseudomonas

42P4 (six times more) (Perez-Rodriguez et al.,

2020a),

an excessive concentration of IAA may have led to an inhibitory effect.

Considering this, we had previously tested lower Enterobacter dilutions

(104, 105

and 106 CFU mL-1)

and observed no rooting promotion. Another plausible explanation is the plant

recognizing Enterobacter as a pathogen. However, this would indicate a

species-specific response. In this regard, we previously reported Enterobacter

promoted growth in pepper and tomato (Perez-Rodriguez et al.,

2020a; Lobato Ureche et al., 2021).

Rooting capacity

varied with rootstock (Keller 2020; Ollat et al., 2016). We found that

101-14 MGt showed the highest rooting compared with the control treatment,

followed by 1103 P and 110R, while SO4 had the lowest rooting (figure 2, figure 3, figure 4, and figure 5). SO4 (Berlandieri-Riparia

family), 1103 P (Berlandieri-Rupestris family), and 110R (Berlandieri-Rupestris

family) were expected to have lower rooting capacity than 101-14 MGt (Riparia-Rupestris

family), because they are hybrids of V. berlandieri, an American

difficult-to-root Vitis species (Keller et al., 2020; Riaz et

al., 2019). Cuttings of 1103 P incubated with Pseudomonas 42P4

showed increased rooting compared to the control. Additionally, rooting

percentage was 15% higher than with the synthetic rooting agent IBA, which only

promoted two of the four assessed parameters. However, contrasting reports

exist regarding IBA’s effectiveness in 1103 P (Boeno et al., 2023;

Daskalakis et al., 2018; Gordillo et al., 2022; Satisha et al.,

2008).

Rooting of 110 R, 101-14, and SO4 cuttings inoculated with Pseudomonas showed

no significant improvements compared to the control. Isçi et

al. (2019) evaluated a commercial bacteria consortium on Ramsey rootstock

after nursery forcing, successfully increasing rooting percentage and root DW

compared to IBA. Rootstock response to Pseudomonas 42P4 and IBA

treatments may depend on genetic diversity and the presence of inhibitors (Wilson

and Van Staden, 1990).

Scion-rootstock

union percentage in SO4 cuttings inoculated with Pseudomonas 42P4 was

threefold higher than in water or with IBA (75% vs. 25%). This result aligns

with Köse

et al. (2005), who reported that Pseudomonas BA8 promoted graft union

of the Italia and Beyaz Çavuş scions onto 41B and 5BB rootstocks. Similarly, Toffanin

et al. (2016) evaluated the effect of inoculating nine rootstock cuttings

with Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 and found improved union only in 1103

P grafted onto Sangiovese. Likewise, A. brasilense Sp245 only improved

the union of Colorino grafted onto 420A (Bartolini et al., 2017). Our native Pseudomonas’

failure to improve graft union in three out of the four evaluated

rootstocks could be explained by impaired polar auxin transport. Auxins may not

have moved towards the rootstock-scion union, but rather accumulate at the

cutting’s basal end, probably given its genetic origin. V. riparia and V.

berlandieri develop callus on both extremities, while V. rupestris predominantly

forms it on the upper extremity (Galet, 1993).

Considering the Vitis genus cuttings lack preformed root

primordia, adventitious root formation is a prerequisite for successful cutting

propagation (Hartmann et al., 2014).

Once cuttings are removed from the plant (wounding), a series of wound

responses occur, and de novo adventitious root generation proceeds. De

novo adventitious rooting involves four stages: cell dedifferentiation

(possibly medullary rays in grapevine), cell proliferation, development and

organization of root primordia, and growth of root primordia (Hartmann

et al., 2014). In early rooting stages, high auxin concentrations either

from buds or exogenous sources like IAA are necessary for dedifferentiation and

cell proliferation (Hartmann et al., 2014; Jarvis,

1986). Under our conditions, the native Pseudomonas synthetised

and exuded IAA into the medium where bacteria had grown and cuttings were

incubated. Although we do not know whether the strains can colonise cuttings

endophytically or epiphytically, we believe bacteria may have produced IAA in

the medium, promoting rooting. Currently, IBA and NAA are the most commonly

used auxins in nurseries (Waite et al., 2014).

Synthetic growth regulators often excessively used, can be sufficiently

replaced by organic products for plant rooting, at least for some species and

varieties (Atak et al., 2024).

However, further investigation should consider the mechanisms underlying

bacterium-plant interaction between Pseudomonas 42P4 and Vitis spp.

and long-term effects.

Conclusions

Pseudomonas 42P4, but not Enterobacter 64S1

promoted rooting (rooting percentage, root number and biomass per cutting) of

Malbec cuttings reaching similar values as IBA 1000 ppm. Furthermore, this

strain increased 1103 P rooting (rooting percentage, root number and biomass

per cutting), compared to the water treatment, but. This was not observed in

101-14 MGt, 110 R or SO4. In 1103 P, this strain increased rooting percentage,

exceeding IBA treatment. Pseudomonas 42P4 also increased SO4 graft union

threefold compared to IBA and water. The use of this bacterium, native to arid

soils, enhances rooting parameters of ungrafted and grafted V. vinifera cv.

Malbec cuttings. This capacity of Pseudomonas 42P4 presents a promising

sustainable alternative for improving grapevine production in commercial nurseries.

Acknowledgements

The authors would

like to thank Diana Segura, Micaela Perez-Rodriguez, Martín López, Walter Tulle

and Carlos Blanquer for their assistance with morphological measurements.

This study was

supported through funding from Fondo para la Investigación Científica y

Tecnológica de Argentina (FONCYT, PICT 2020-3618 to ACC); Universidad Nacional

de Cuyo (SIIP-UNCUYO M021-T1 to CVG and ACC), Fundación Williams (to ACC) and

CONICET (PIP-KA1 11220210100195CO to ACC and CVG).

ACC and CVG are CONICET researchers and UNCUYO Professors, MGG

is a PhD fellow from CONICET and FC is a member of Trapiche winery staff.

Atak, A. (2024).

Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.). Open

Agriculture, 9, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2022-0258

Bartolini, S.,

Carrozza, G., Scalabrelli, G., & Toffanin, A. (2017). Effectiveness of Azospirillum

brasilense Sp245 on young plants of Vitis vinifera L. Open Life

Sciences, 12, 365-372. https://doi. org/10.1515/biol-2017-0042

Berdugo, M.,

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Soliveres, S., Hernandez-Clemente, R., Zhao, Y., Gaitan,

JJ, Gross, N., Saiz, H., Maire, V., & Lehmann, A. (2020). Global ecosystem

thresholds driven by aridity. Science, 367, 787-790.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay5958

Boeno, D., &

Zuffellato-Ribas, KC. (2023). A quantitative assessment of factors affecting

the rooting of grapevine rootstocks (Vitis vinifera L.). Acta

Scientiarum Agronomy, 45. https://doi.

org/10.4025/actasciagron.v45i1.57987

Brunoni, F.,

Vielba, JN, & Sanchez, C. (2022). Plant growth regulators in tree rooting. Plants,

11(6), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11060805

Burrel, AL, Evans,

JP, & De Kauwe, MG. (2020). Anthropogenic climate change has driven over 5

million km2 of drylands

towards desertification. Nature Communications, 11, 3853.

https://doi. org/10.1038/s41467-020-17710-7

Centeno, A., &

Gómez del Campo, M. (2008). Effect of root-promoting products in the

propagation of organic olive (Olea europaea L. cv. Cornicabra). HortScience,

43(7), 2066-2069. https:// doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.43.7.2066

Daskalakis, I.,

Biniari, K., Bouza, D., & Stavrakaki, M. (2018). The effect that

indolebutyric acid (IBA) and position of cane segment have on the rooting of

cuttings from grapevine rootstocks and from Cabernet Franc (Vitis vinifera L.)

under conditions of a hydroponic culture system. Scientia Horticulturae,

227, 79-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.09.024

D’Innocenzo, SH,

Escoriaza, G, Diaz, ME. (2024). First report of the causal agent of vine crown

gall in Mendoza, Argentina. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 56(2): 87-96. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.139

Di Rienzo, JA,

Casanoves, F., Balzarini, MG, Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., & Robledo, CW.

(2020). InfoStat 2020/P. https://www.infostat.com.ar/

Flexas, J., Galmés,

J., Gallé, A., Gulías, J., Pou, A., Ribas-Carbó, M., Tomas, M., & Medrano,

H. (2010). Improving water use efficiency in grapevines: Potential

physiological targets for biotechnological improvement. Australian Journal

of Grape and Wine Research, 16, 106 121.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.2009.00057.x

Galet, P. (1993). Précis

de viticulture. Dehan Ed.

Garay-Arroyo, A.,

de La Paz Sánchez, M., García-Ponce, B., Álvarez-Buylla, ER & Gutiérrez, C.

(2014). La homeostasis de las auxinas y su importancia. Revista de Educación

Bioquímica, 33(1), 13-22.

Glick, BR. (2012).

Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Mechanisms and applications. Scientifica,

2012, 963401. https://doi.org/10.6064/2012/963401

Gordillo, MG,

Cohen, AC, Roge, M., Belmonte, M., & González, CV. (2022). Effect of

quick-dip with increasing doses of IBA on rooting of five grapevine rootstocks

grafted with ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. Vitis, 61(3), 147-152.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5073/vitis.2022.61.147-152

Hartmann, HT,

Kester, DE, Davies, FT, Jr., & Geneve, RL. (2014). Plant propagation:

Principles and practices (8th ed.).

Pearson.

Instituto Nacional

de Vitivinicultura. (2023). Superficie cultivada con viñedos en Argentina.

https:// www.argentina.gob.ar/inv/vinos/estadisticas

Isçi, B., Kacar,

E., & Altindisli, A. (2019). Effects of IBA and plant growth-promoting

rhizobacteria (PGPR) on rooting of ramsey american grapevine rootstock. Applied

Ecology and Environmental Research, 17(2), 4693-4705.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1702_46934705

Jarvis, BC. (1986). Endogenous control of adventitious rooting

in non-woody species. En M. B. Jackson (Ed.), New root formation in plants

and cuttings (p. 137-162). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4358-2_6

Jofré, MF, Mammana,

S., Pérez-Rodríguez, MM, Silva, MF, Gómez, F., & Cohen, AC. (2024). Native

rhizobacteria improve drought tolerance in tomato plants by increasing endogenous

melatonin levels and photosynthetic efficiency. Scientia Horticulturae, 329,

112984. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.112984

Keller, M. (2020). The

science of grapevines (3rd ed.).

Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12- 816365-8.00001-4

Köse, C., Güleryüz,

M., Şahin, F., & Demirtaş, İ. (2003). Effects of some plant growth

promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on rooting of grapevine rootstocks. Acta

Agrobotanica, 56(1), 47-52. https://doi.org/10.5586/aa.2003.005

Köse, C., Güleryüz,

M., Şahin, F., & Demirtaş, İ. (2005). Effects of some plant growth

promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on graft union of grapevine. Journal of

Sustainable Agriculture, 26(2), 139-147.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v26n02_10

Lobato Ureche, MA,

Perez-Rodriguez, MM, Ortiz, R., Monasterio, RP, & Cohen, AC. (2021).

Rhizobacteria improve the germination and modify the phenolic compound profile

of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Rhizosphere, 18, 100334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rhisph.2021.100334

Machado, MP, Mayer,

JLS, Ritter, M., & Biasi, LA. (2005). Indole butyric acid on rooting

ability of semihardwood cutting of grapevine rootstock ‘VR 043-43’ (Vitis

vinifera x Vitis rotundifolia). Revista Brasileira de

Fruticultura, 27(3), 476-479.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-29452005000300032

Mudge, K., Janick,

J., Scofield, S., & Goldschmidt, EE. (2009). A history of grafting. Horticultural

Reviews, 35, 437-483. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470593776.CH9

OIV (International

Organization of Vine and Wine). (2023). State of the world vine and wine

sector. https://www.oiv.int/node

Ollat, N.,

Bordenave, L., Tandonnet, JP, Boursiquot, JM, & Marguerit, E. (2016).

Grapevine rootstocks: Origins and perspectives. Acta Horticulturae, 1136,

11-22. https://doi.org/10.17660/ ActaHortic.2016.1136.2

Pantoja Guerra, M.,

Valero Valero, N., & Ramírez, CA. (2023). Total auxin level in the

soil-plant system as a modulating factor for the effectiveness of PGPR inocula:

A review. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 10,

6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-022-00370-8

Pérez-Rodríguez,

MM, Piccoli, P., Anzuay, MS., Baraldi, R., Neri, L., Taurian, T., Lobato

Ureche, MA, Segura, DM, & Cohen, AC. (2020a). Native bacteria isolated from

roots and rhizosphere of Solanum lycopersicum L. increase tomato

seedling growth under a reduced fertilization regime. Scientific Reports,

10, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72507-4

Pérez-Rodríguez,

MM, Pontin, M., Lipinski, V., Botini, R., Piccoli, P., & Cohen, AC.

(2020b). Pseudomonas fluorescens and Azospirillum brasilense increase

yield and fruit quality of tomato under field conditions. Journal of Soil

Science and Plant Nutrition, 20(3), 1614-1624. https://doi.

org/10.1007/s42729-020-00233-x

Pérez-Rodríguez,

MM, Pontin, M., Piccoli, P., Lobato Ureche, MA, Gordillo, MG, Funes Pinter, I.,

& Cohen, AC. (2022). Halotolerant native bacteria Enterobacter 64S1

and Pseudomonas 42P4 alleviate saline stress in tomato plants. Physiologia

Plantarum, 174(1), 13472. https://doi. org/10.1111/ppl.13742

R Core Team.

(2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R

Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Riaz, S., Pap, D.,

Uretsky, J., Laucou, V., Boursiquot, JM, & Kocsis, L. (2019). Genetic

diversity and parentage analysis of grape rootstocks. Theoretical and

Applied Genetics, 132(6), 1847-1860. https://

doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03320-5

Satisha, J., &

Asdule, PG. (2008). Rooting behaviour of grape rootstocks in relation to IBA

concentration and biochemical constituents of mother vines. Acta

Horticulturae, 785, 121-125. https://

doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2008.785.14

Tandonnet, JP,

Cookson, SJ, Vivin, P., & Ollat, N. (2009). Scion genotype controls biomass

allocation and root development in grafted grapevine: Scion/rootstock

interactions in grapevine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research,

16(1), 290-300. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1755-0238.2009.00090.x

Toffanin, A.,

D’Onofrio, C., Carroza, GP, & Scalabrelli, G. (2016). Use of beneficial

bacteria Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on grapevine rootstocks grafted

with ‘Sangiovese’. Acta Horticulturae, 1136, 24.

https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2016.1136.24

Waite, H.,

Whitelaw-Weckert, M., & Torley, P. (2014). Grapevine propagation:

Principles and methods for the production of high-quality grapevine planting

material. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science, 43(2),

144-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/01140671.201 4.978340

Wickham, H. (2016).

ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag.

https://ggplot2. tidyverse.org

Wilson, PJ, & Van Staden, J. (1990). Rhizocaline, rooting

co-factors, and the concept of promoters and inhibitors of adventitious rooting

- A review. Annals of Botany, 66(4), 479-490. https://doi.

org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a088051