Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. En prensa. ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Original article

Radial

Growth Dynamics and Drought Resilience in Pinus pinea L. Plantations

from Central-Western Argentina: Implications for Forestry Development

Dinámica

del Crecimiento radial y resiliencia a la sequía de Pinus pinea L. en

plantaciones del centro-oeste argentino: implicancias forestales

Luciano Diaz

Dentoni3,

1Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias

Ambientales. Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas

(IANIGLA CONICET). Laboratorio de Dendrocronología e Historia Ambiental. Av.

Dr. Adrian Ruiz Leal. Parque Gral. San Martín. M5500 Mendoza. Argentina.

2Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Cátedra de Economía y Política Agraria. Almirante Brown 500. M5528AHB. Chacras

de Coria. Mendoza. Argentina.

3Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Almirante Brown 500. M5528AHB. Chacras de Coria. Mendoza. Argentina.

4Universidad Mayor. Facultad de Ciencias. Hémera Centro de

Observación de la Tierra. Camino La Pirámide 5750. Huechuraba. Santiago.Chile.

*spiraino@fca.uncu.edu.ar

Abstract

Forests play a

crucial role in ecological stability, carbon sequestration, habitat provision and economy. As climate change intensifies, increasing

drought frequency and severity challenge our understanding of forest

resilience. Based on this premise, we examined radial growth dynamics and

drought response of Pinus pinea L. in Mendoza Province in both mesic and

xeric conditions. Using dendrochronological techniques, we assessed the long

and short-term effects of soil and atmospheric drought on radial growth trends

at two irrigated plantations with contrasting environments. Growth dynamics

reflected differences in soil, climate, and irrigation. Growth rates were

significantly higher at the mesic stand, which received nearly twice the

precipitation and irrigation compared to xeric one. In contrast, growth at the

xeric site was strongly limited by early-summer atmospheric drought, while

late-growing season soil moisture and climatic conditions affected tree-ring

development at the mesic site. Growth resilience to extreme events experienced

site dependence, with edaphic drought exerting a stronger negative effect than

atmospheric dry spells at the mesic stand. Our results underscore the

importance of integrating short- and long-term drought assessment into P.

pinea management strategies and support the potential of stone pine

plantations in extra-Mediterranean South America for sustainable forestry under

changing climatic conditions.

Keywords: climate change,

forest management, mendoza, tree-rings

Resumen

Los bosques son

esenciales en la estabilidad ecológica, la captura de carbono, la provisión de

hábitats y de recursos económicos. Ante el aumento de la frecuencia y severidad

de las sequías asociado al cambio climático,

comprender la resiliencia forestal resulta crucial. Este estudio analizó

mediante métodos dendrocronológicos los efectos a corto y largo plazo de las

sequías edáficas y atmosféricas sobre el crecimiento radial de Pinus pinea L.

en dos plantaciones irrigadas bajo condiciones ambientales contrastantes en el

centro-oeste argentino. Los patrones de crecimiento reflejaron diferencias

ambientales y de manejo. Las tasas de crecimiento fueron significativamente

mayores en el rodal mésico, que recibió casi el doble de precipitación e

irrigación que el xérico. En este último, el crecimiento se vio limitado por

sequías atmosféricas de comienzo del verano, mientras que en el mésico

influyeron las sequías edáficas y climáticas al final de la temporada de

crecimiento. La resiliencia ante eventos extremos mostró dependencia del sitio,

con un efecto negativo más marcado de la sequía edáfica en el rodal mésico. Los

resultados destacan la necesidad de integrar evaluaciones multitemporales de

sequía en el manejo de P. pinea y su potencial para un desarrollo forestal

sostenible en regiones extra-Mediterráneas de Sudamérica.

Palabras clave: cambio climático,

manejo forestal, Mendoza, anillos de crecimiento de árboles

Originales: Recepción: 20/05/2025 - Aceptación: 21/10/2025

Introduction

Forests maintain ecological

balance by storing carbon, regulating water cycles, and providing habitat for

numerous species (Barnes et al., 1997).

Recent climatic shifts have increased the focus on the resilience of natural

and planted forests under abiotic disturbances (Johnstone

et al., 2016). Drought threatens forest health and productivity, as

dry spells become more frequent and intense (IPCC, 2023).

Extreme drought events have severely impacted forests, reducing growth rates

and increasing tree mortality (Allen et al., 2010).

Due to their

genetic uniformity, plantation forests may respond differently to dry spells

than natural woodlands (Camarero et al., 2021;

Navarro-Cerrillo et al., 2023). Their capacity to withstand and

recover from a drought event dictates their long-term sustainability and

broader environmental and economic values. Even considering that forest

plantations only cover about 7% of the global forest area, they significantly

contribute to mitigating deforestation impacts on natural woodlands (FAO, 2020). This provides particular importance to the

in-depth understanding of their drought resilience.

Drought stress

manifests in two primary forms: atmospheric drought, driven by low humidity and

high evaporative demand, and edaphic drought, characterized by depleted soil

water (Mishra & Singh, 2010). These conditions

can occur separately or together, each uniquely impacting plant growth (Knutzen et al., 2017). Disentangling these

responses is key to predicting how trees will perform in a changing climate.

Forest responses to

extreme drought can be assessed by analyzing long- and short-term growth

trends. Long-term trends reveal climate-growth relationships, while short-term

responses measure resilience, that is, the capacity to withstand and recover

from dry spells (Lloret et al., 2011).

Dendrochronology provides a powerful method for investigating tree growth

responses to ecological variables, allowing us to reconstruct growth trends and

identify periods of stress, thereby illuminating species’ resilience and

adaptability (Piraino, 2020; Piraino et al.,

2022, 2024).

Pinus pinea L. (stone pine), a conifer prized for its edible seeds, holds

significant ecological and economic value (Mutke et

al., 2012). In its native Mediterranean range, the species now suffers

drought-related decline in cone yield (Calama et al.,

2020). Climate models project a contraction of its suitable habitat and a

negative trend in radial growth (Mechergui et al.,

2021; Natalini et al., 2024). Establishing extra-Mediterranean

plantations could help offset the impending global shortfall in nut production.

Growers have

successfully introduced stone pine to southern South America (Chile and

Argentina) (Muñoz et al., 2012), where it

adapts well to diverse conditions and promises economic benefits from

non-timber products (Loewe-Muñoz et al., 2012).

Recent studies have analyzed tree-ring variability and its relationship with

climate trends and extremes in Chilean plantations under typical Mediterranean

conditions (Loewe Muñoz et al., 2024ab). However,

no research has yet reconstructed radial growth dynamics in Argentina, where

the species thrives in semi-arid environments (Calderón et

al., 2008; Diaz Dentoni, 2024).

This study aims to

investigate how P. pinea radial growth interacts with drought

conditions in two irrigated plantations located in Argentina’s Mendoza

Province. We hypothesize that drought events significantly suppress growth,

with the stronger effects during extreme dry years. Our findings will clarify

the potential of this species for forestry in extra-Mediterranean regions,

especially as climate change threatens its native range.

Material

and Methods

Study

Site Characteristics

We selected two sites for this study: Dique Yaucha (hereafter

YAU; 34°00’03” S,

69°07’03” W) and Malargüe (hereafter MAL: 35°35’55” S, 69°31’37”

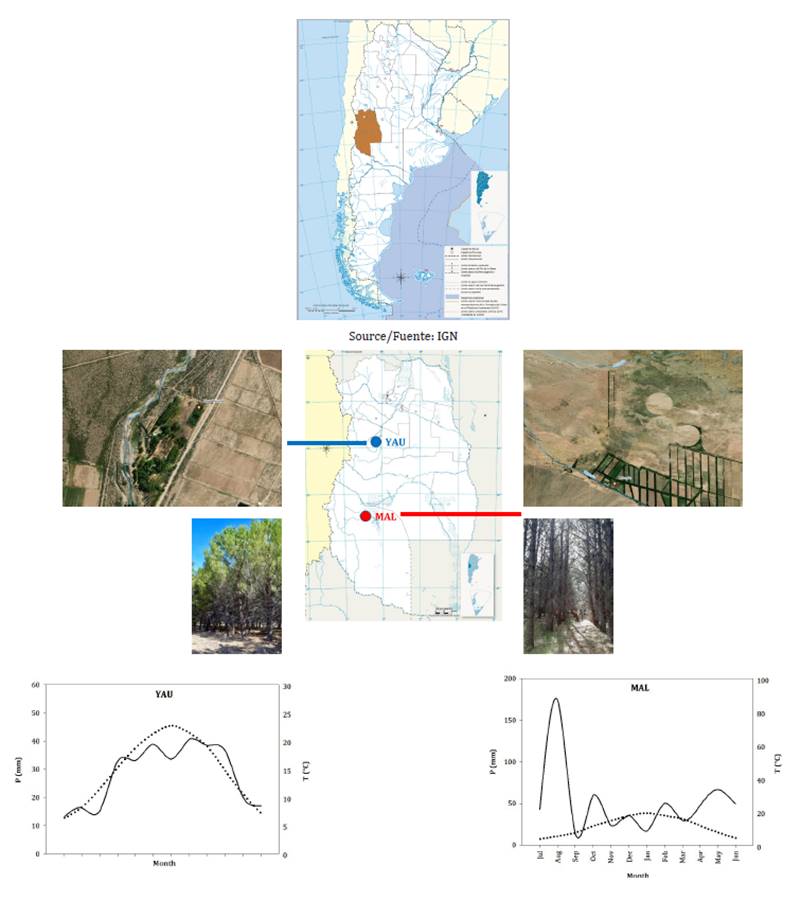

W), both located in southern Mendoza Province (figure 1).

These plantations represent the only undisturbed adult artificial forests in

the region (Piraino et al., 2021).

Precipitation

and temperature data belong to the INTA San Carlos (Dique Yaucha: 33.73°S,

69.1°W; http://siga.inta.gob.ar/#/), and Malargüe Aero (Malargüe: 35.48°S;

69.58°W; http://www.meteomanz.com/) gauge stations, covering the 2000-2020

period. T: monthly mean air temperature; P: monthly total rainfall. Gray dot

line refers to monthly mean air temperature, and black solid line to monthly

total rainfall.

Los

datos de precipitación y temperatura pertenecen a las estaciones climáticas

INTA San Carlos (Dique Yaucha: 33.73°S, 69.1°O; http:// siga.inta.gob.ar/#/) y

Malargüe Aero (Malargüe: 35.48°S; 69.58°O; http://www.meteomanz.com/), y cubren

el período 2000-2020. T: temperatura media mensual del aire; P: precipitación

total mensual. La línea de puntos grises indica la temperatura media mensual

del aire, y la línea negra continua, la precipitación total mensual.

Figure

1.

Geographical location of the sampled sites and Ombrothermic diagram drawn

according to the methods of Bagnouls

& Gaussen (1953).

Figura

1. Ubicación geográfica de los sitios muestreados y diagrama

ombrotérmico elaborado según los métodos de Bagnouls

& Gaussen (1953).

At both sites,

stone pine seedlings were planted between the late 1980s and early 1990s,

forming a monospecific plantation with a spacing of 3x3 m between rows and

trees. The plantations are situated at similar elevations (1213 m a. s. l. for

YAU vs 1470 m a. s. l. for MAL). The YAU site is characterized by semi-arid

conditions, with mean annual temperature of 15°C, and total annual

precipitation of 335 mm (figure 1). In contrast, MAL grows

under Mediterranean-type climate, with mean annual temperature and total annual

precipitation values of 12.6°C and 610 mm, respectively (figure 1).

Soils are gravelly to sandy with good permeability at YAU, and loam to clay

loam of alluvial origin at MAL. Both plantations receive supplementary

irrigation: approximately 300-350 mm annually at YAU and 500-600 mm at MAL,

evenly distributed across the irrigation season (September-July; current and

projected upper river water balance 2020-2021; G. Aguado, personal

communication). According to this characterization, we considered YAU and

MAL sites xeric and mesic, respectively.

Dendrochronological

Sampling and Tree-Ring Chronology Development

During the austral

spring of 2021 and 2022, we extracted one core per tree at breast height

(approximately 1.30 m above soil level) from 16 individuals at YAU and 10 at

MAL, respectively, by using a 5.15 mm increment borer. We selected sampled

trees based on their health status. Cores were glued onto wooden mounts, and

the transverse section was polished with progressively finer sandpaper to

highlight ring boundaries. Samples were scanned at 1200 dpi, and tree-ring

width (TRW) was measured to 0.001 mm precision with CooRecorder software (Maxwell & Larsson, 2021). Calendar years were

assigned following Schulman’s convention for the Southern Hemisphere (Schulman, 1956).

TRW series were

statistically validated with COFECHA software (Holmes,

1983). Two indices were calculated: 1) the mean correlation among

individual series (MC); and 2) mean sensitivity (MS), the relative year-to-year

variability in TRW, reflecting the species’ sensitivity to environmental

factors (Speer, 2010).

After statistical validation, individual chronologies were

standardized to remove the low-frequency, age-related trends and highlight the

high-frequency climate signal (Speer, 2010). Raw TRW

series were detrended using a 20-years spline with a 50% frequency cutoff

applied in ARSTAN40c software (Cook & Krusic, 2006). We used the

standardized residual chronology version for all drought-growth analyses to

minimize bias from non-climatic trends (Villalba &

Veblen, 1997).

Statistical

Analyses

To assess

differences in TRW trends among sites under varying environmental conditions,

we compared the raw ring-width site chronologies for the common period

1992-2020 with a Kruskal-Wallis test hosted in the InfoStat software (Di Rienzo et al., 2021). Then, we used site and

individual- standardized chronologies to evaluate the effect of drought on

growth at long and short-term timescales. For the long-term analysis,

correlation functions were calculated between the standardized

site-chronologies and two datasets: SPEI (Standardized Precipitation

Evaporation Index; Vicente-Serrano et al., 2010),

and soil moisture at 100 cm depth (SM100). Monthly values of both datasets were

obtained from the KNMI Climate Explorer for 1901-2018 (SPEI) and 1979-2016

(SM100) (Trouet & Van Oldenborgh, 2013; http://climexp.knmi.nl/). Correlation

functions were computed with DENDROCLIM2002 for the common period 1992-2016 (n

= 25) (Biondi & Waikul, 2004). We selected this

interval because the YAU chronology began in 1992 and SM100 data ended in 2016.

Based on prior research, stone pine plantations in South America (Loewe-Muñoz et al., 2022), a 13-month

time-window was selected, spanning June of the year preceding growth through June

of the growth year. No monthly irrigation data were available, which prevented

direct comparison between supplementary water inputs and ring development.

We assessed

short-term growth responses to extreme drought using the line of full

resilience (LFR; Schwarz et al., 2020). The

LFR approach evaluates the relationship between resistance and recovery sensu

Lloret et al., 2011; see below for

mathematical definitions. and compares it with the

theoretical scenario of full resilience (Schwarz et

al., 2020). This method provides an integrated assessment of tree

capacity to withstand drought stress (Schwarz et al.,

2020).

We defined drought

years based on the significant monthly windows identified by the correlation

function analysis, which we used to calculate annual series for SPEI and SM100.

We classified years with SPEI or SM100 values in the lowest 5th percentile as extreme

drought events. For these events, we calculated tree-level resistance (Rt)

and

recovery (Rc) indices as Rt = TRId/TRI_pred and Rc

= TRI_postd/TRId. TRI is the standardized

tree-ring index, d refers to the drought year, and pre and post

denote the year before and after extreme dry spell, respectively (Lloret et al., 2011). Short pre and

post time windows were chosen to minimize overlap among consecutive

drought events (see Results). Finally, Finally, we calculated the LFR as Rc = 1/Rt.

Results

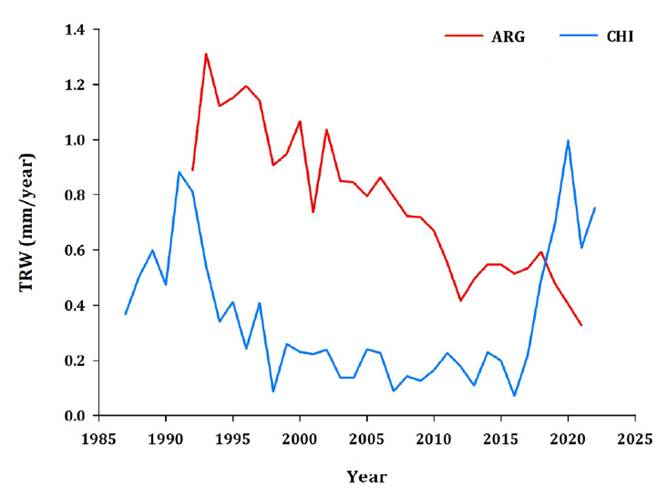

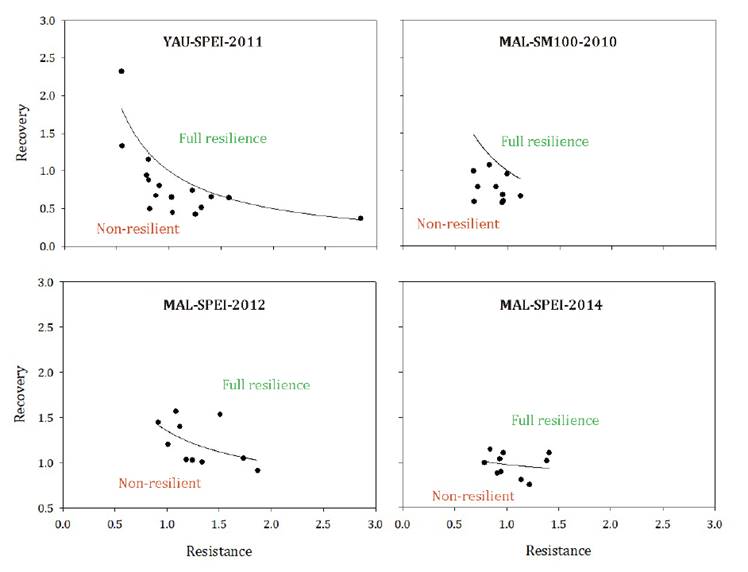

We developed two

tree-ring chronologies from 10 (MAL) and 16 (YAU) wood samples (table

1 and figure 2). The chronologies covered 1991-2020 at

MAL and 1992-2021 at YAU (table 1). Mean annual raw TRW

(mTRW) was significantly higher at MAL than at YAU stand (H = 8.35; p =

0.0039; data not shown). Tree-ring statistics showed higher MC and MS values

for YAU (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the tree-ring chronologies.

Tabla

1. Características de las cronologías de anillos de crecimiento.

N:

Number of sampled trees per site. Period: time range of the sampled cores. mTRW: mean annual tree-ring width value. MC: mean

correlation between series at each stand. MS: mean sensitivity.

N:

Número de árboles muestreados por sitio. Period: rango temporal de las

muestras. mTRW: valor medio anual del ancho de anillo.

MC: correlación media entre series en cada rodal. MS: sensibilidad media.

Figure

2.

Raw tree-ring width (TRW) site chronologies of the sampled stone pine

plantations.

Figura

2. Cronologías de datos brutos de ancho de anillo (TRW) de las

plantaciones de pino piñonero muestreadas.

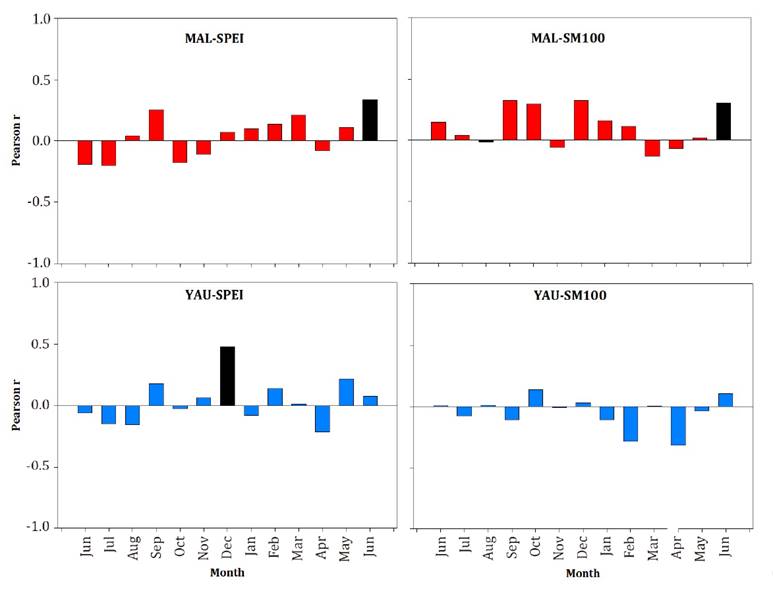

Correlation function analyses

revealed that radial growth at both sites was significantly influenced by

long-term drought conditions, although responses differed between stands (figure 3). At MAL, standardized growth was positively related to

late spring (June; JUN) SPEI and SM100. At YAU, SPEI positively influenced ring

width during December (DEC) of the year of growth, while no significant relationship

emerged with SM100 (figure 3).

Black

bars refer to significant Pearson r values at p < 0.05 level.

Las

barras negras indican valores de correlación de Pearson significativos por p

< 0,05.

Figure

3.

Correlation functions results between each residual chronology and monthly SPEI

and SM100 values for the common period 1992-2016.

Figura

3. Resultados de las funciones de correlación entre cada

cronología residual y los valores mensuales de SPEI y SM100 para el período

común 1992-2016.

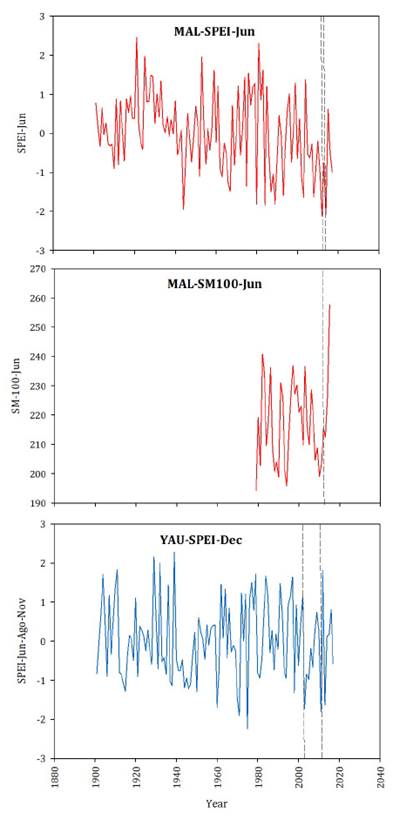

Based on these

results, we selected JUN-SM100 and JUN-SPEI to identify extreme drought events

at MAL, and DEC-SPEI at YAU stand. Statistical analyses identified three

extreme drought events at MAL (MAL-SM100 2010: MAL-SPEI 2012; MAL-SPEI 2014)

and two at YAU (YAU-SPEI 2003 and YAU -SPEI 2011) (figure 4).

We excluded the YAU -SPEI 2003 event, as trees were likely in their seedling

phase.

Vertical

lines refer to local extreme drought events.

Las

líneas verticales indican los eventos locales de sequía extrema.

Figure

4.

Historical series of SPEI and SM100 at each site based on correlation function

results.

Figura

4. Series históricas de SPEI y SM100 por cada sitio, basadas

en los resultados de las funciones de correlación.

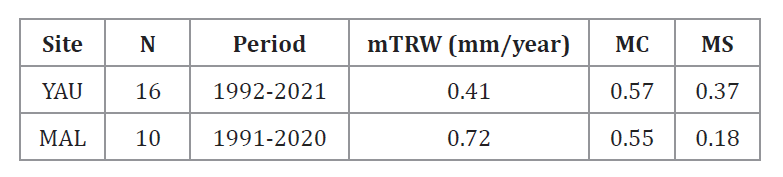

LFR analysis revealed contrasting responses among stands (figure 5). At YAU, only 6% of trees displayed full resilience to

the 2011 extreme drought. At MAL, no tree exhibited full resilience to the 2010

SM100 event. In contrast, LFR values were comparable between the MAL-SPEI 2012

(LFR = 40%) and the MAL-SPEI 2014 (LFR = 50%) events (figure 5).

Dots

located above the LFR correspond to trees exhibiting full resilience

(Resilience = 1.0).

Los

puntos situados por encima de la LFR corresponden a los árboles que exhiben

resiliencia plena (Resiliencia = 1.0).

Figure

5.

Comparison of the relationship between observed tree-level mean values of Rt and Rc and the

hypothetical function (black curve) representing the LFR across all Rt values,

for the analyzed extreme atmospheric and edaphic drought events.

Figura

5. Comparación de la relación entre los valores medios

observados a nivel de árbol de Rt y Rc y la función hipotética (curva negra) que

representa la LFR a lo largo de todos los valores de Rt, para los eventos analizados de sequía

atmosférica y edáfica extrema.

Discussion

This study provided novel information of how stone pine growing

in an extra-Mediterranean region responds to atmospheric and edaphic drought

across multiple timescales. Previous research addressed the species’

dendroclimatological signal and resilience to extreme climatic events in Chile

(Loewe-Muñoz et al., 2024ab), but no studies

had explored these dynamics under the environmental conditions of

central-western Argentina. Our findings offer new insights of P. pinea growth

and drought resilience beyond its native Mediterranean habitat, confirming the

species’ adaptability to new climatic contexts.

Although our sample

size was relatively small, it well represented growth dynamics of both

populations. At MAL, sampled trees accounted for 85% of the original plantation

(n = 12). At YAU, the tree-ring chronology reliably captured stand-level

growth, with an Expressed Population Signal (EPS; Wigley

et al., 1984) exceeding the 0.85 threshold, indicating strong

agreement between sampled trees and the overall population (data not shown).

The mean

correlation coefficient among individual series fell within the range reported

in literature, confirming the robustness of our ring-width measurements (Natalini et al., 2016; Piraino

et al., 2013). At YAU, MS was twice as high as at MAL.

Theoretically, MS should reflect MC variability, since both indices are

strongly related (Fritts et al., 1965).

Nevertheless, MC differed only slightly between stands. The higher irrigation

regime at MAL likely explained the differences in MS values by reducing growth

sensitivity to environmental variability. This interpretation agrees with

previous studies in Central European conifer comparing irrigated and

non-irrigated woodlands (Feichtinger et al.,

2014; Rigling et al., 2003).

Mean TRW at both

sites exceeded values previously reported (Mechergui et

al., 2021). This pattern likely reflects both the relatively young age

of the plantations, with trees probably still at their juvenile growth phase,

and the benefit of irrigation, which can extend the growing season, enhance

nutrient mobility, and increase primary production (Feichtinger

et al., 2014; Loewe-Muñoz et al., 2024a). The higher mTRW at

MAL compared with YAU further reflects the more favorable water balance at that

site (precipitation + irrigation: see Materials and Methods).

Our analyses of

drought-radial growth relationships across timescales indicated that irrigation

did not fully decouple growth from climate, suggesting that the supplementary

water was likely insufficient (Perulli et al., 2019).

This limitation was particularly evident at YAU, where radial growth benefited only

during the early phases of ring development. These results have practical

implications for managing future plantations in semi-arid central-west

Argentina. However, the lack of systematic irrigation records prevented

statistical evaluation of watering effect. For future P. pinea plantations

in Mendoza, we recommend monitoring irrigation at least monthly to enable

direct comparison between radial growth dynamics and water supply.

Correlation

function analyses provided quantitative evidence of the species’ distinct

responses to atmospheric and edaphic drought. At MAL, radial growth correlated

with high soil moisture and wet atmospheric conditions at the end of the

growing season. In contrast, at YAU, ring width responded positively to early

summer (December) SPEI. Previous studies in the Mediterranean range reported

similar patterns, showing that radial growth benefits from low

evapotranspiration during the growing season and from abundant precipitation

before cambium reactivation (Mechergui et al.,

2021). Physiologically, P. pinea is a drought-tolerant species,

capable of reducing photosynthetic activity during water stress through root

mortality, stomata control, and biomass allocation (Mechergui

et al., 2021). Nevertheless, drought constrains tree growth by

reducing sap flow and significantly decreasing stem increment (Mechergui et al., 2021; Piraino, 2020). Our

findings confirm that, regardless of irrigation, the species’ radial growth

remains constrained by unfavorable environmental conditions during the growing

period (Loewe-Muñoz et al., 2024b; Piraino, 2020).

Analysis of annual SPEI and SM100 series identified several

extreme drought events that impacted growth dynamics at both sites. At MAL,

edaphic dry spells exerted stronger short-term effects on growth than

atmospheric droughts. This difference may reflect the direct impact of soil

water deficit on roots uptake, whereas atmospheric drought primarily affects

transpiration and leaf water potential, which may not immediately restrict stem

growth if surface soil moisture remains sufficient (Berauer

et al., 2024). Future studies should integrate physiological data

from both root and stem levels, along with site-specific infiltration rates, to

better characterize the species responses to different drought types.

Conclusion

Our study provides critical baseline data on the radial growth

and drought resilience of P. pinea, establishing a foundation for

evaluating its potential for forestry development beyond Mediterranean

environments. These findings are especially relevant for Mendoza Province,

where current forestry focuses almost exclusively on medium-quality wood

production from more water-demanding species like as Populus spp.

Expanding P. pinea cultivation would diversify local forestry and could

yield substantial economic benefits under the semi-arid conditions of

central-western Argentina.

Allen,

C. D., Macalady, A. K., Chenchouni, H., Bachelet, D., McDowell, N., Vennetier,

M., Kitzberger, T., Rigling , A., Breshears, D. D., Hogg, E. H., Gonzalez, P.,

Fensham, R., Zhang, Z., Castro, J., Demidova, N., Lim, J. N., Allard, G., S.,

Running S. W., Semerci, A., Cobb, N. (2010). A global overview of drought and

heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest

ecology and management, 259(4), 660-684.

Bagnouls,

F. (1953). Saison sèche et indice xérothermique. Bull Soc His nat Toulouse,

88, 193-239.

Barnes,

B. V., Zak, D. R., Denton, S. R., & Spurr, S. H. (1997). IForest ecology

(N° Ed. 4, p. xviii+-774).

Berauer,

B. J., Steppuhn, A., & Schweiger, A. H. (2024). The multidimensionality of

plant drought stress: The relative importance of edaphic and atmospheric

drought. Plant, Cell & Environment, 47(9), 3528-3540.

Biondi,

F., & Waikul, K. (2004). DENDROCLIM2002: A C++ program for statistical

calibration of climate signals in tree-ring chronologies. Computers &

geosciences, 30(3), 303-311.

Calama,

R., Gordo, J., Mutke, S., Conde, M., Madrigal, G., Garriga, E., Arias, M. J.,

Piqué, M., Gandía, R., Monterno, G., Pardos, M. (2020). Decline in commercial

pine nut and kernel yield in Mediterranean stone pine (Pinus pinea L.)

in Spain. Forest-Biogeosciences and Forestry, 13(4), 251.

Calderón,

A., Bustamante, J. A., Riu, N., Perez, S. (2008). Conifers behaviour under

irrigation in the Yaucha dam. Mendoza, Argentina. Revista de la Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. 40(1): 67-72. https://bdigital.uncu.edu.ar/app/navegador/?idobjeto=2676

Camarero,

J. J., Gazol, A., Linares, J. C., Fajardo, A., Colangelo, M., Valeriano, C.,

Sánchez-Salguero, R., Sangüesa-Barreda, G., Granda, E., Gimeno, T. E. (2021).

Differences in temperature sensitivity and drought recovery between natural

stands and plantations of conifers are species-specific. Science of the

Total Environment, 796, 148930.

Cook,

E. R., & Krusic, P. J. (2008). A tree-ring standardization program based

on detrending and autoregressive time series modeling, with interactive

graphics (ARSTAN). http://www. ldeo. columbia. edu/res/fac/trl/public/publicSoftware.

html

Diaz

Dentoni, L. (2024). Análisis de la dinámica de crecimiento de Pinus pinea l.

en dos parcelas bajo riego en la provincia de Mendoza. Tesis de grado.

FCA-UNCuyo. 34p.

Di

Rienzo, J., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., Robledo,

C. (2021). InfoStat version 2021.

FAO

(Food and Agriculture Organization). (2020). Global Forest Resources

Assessment 2020: Main report. FAO, Rome.

Feichtinger,

L. M., Eilmann, B., Buchmann, N., & Rigling, A. (2014). Growth adjustments

of conifers to drought and to century-long irrigation. Forest Ecology and

Management, 334, 96-105.

Fritts,

H. C., Smith, D. G., Cardis, J. W., & Budelsky, C. A. (1965). Tree‐ring characteristics along a vegetation

gradient in northern Arizona. Ecology, 46(4), 393-401.

Holmes,

R. L. (1983). Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and

measurement. Tree-Ring Bulletin, Vol. 43. 1-10.

IPCC

(2023). Sections. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of

Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J.

Romero (eds.)]. IPCC. p. 35-115.

Johnstone,

J. F., Allen, C. D., Franklin, J. F., Frelich, L. E., Harvey, B. J., Higuera,

P. E., Mack, M. C., Meentemeyer, R. K., Metz, M. R., Perry, G. L. W.,

Schoennagel, T., Turner, M. G. (2016). Changing disturbance regimes, ecological

memory, and forest resilience. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(7),

369-378.

Knutzen,

F., Dulamsuren, C., Meier, I. C., & Leuschner, C. (2017). Recent climate

warming-related growth decline impairs European beech in the center of its

distribution range. Ecosystems, 20, 1494- 1511.

Lloret,

F., Keeling, E. G., & Sala, A. (2011). Components of tree resilience:

effects of successive low‐growth

episodes in old ponderosa pine forests. Oikos, 120(12), 1909-1920.

Loewe-Muñoz,

V., Del Río, R., Delard, C., Balzarini, M. (2022). A detailed time series of

hourly circumference variations in Pinus pinea L. in Chile. Annals of

Forest Science. 79(1): 4.

Loewe-Muñoz,

V., Del Río, R., Delard, C., Cachinero-Vivar, A. M., Camarero, J. J., Navarro-Cerrillo,

R., & Balzarini, M. (2024a). Resilience of Pinus pinea L. trees to

drought in Central Chile based on tree radial growth methods. Forests, 15(10),

1775.

Loewe-Muñoz,

V., Cachinero-Vivar, A. M., Camarero, J. J., Río, R. D., Delard, C., & Navarro-Cerrillo,

R. M. (2024b). Dendrochronological analysis of Pinus pinea in Central Chile and

South Spain for sustainable forest management. Biology, 13(8), 628.

Maxwell,

R. S., & Larsson, L. A. (2021). Measuring tree-ring widths using the

CooRecorder software application. Dendrochronologia, 67, 125841.

Mechergui,

K., Saleh Altamimi, A., Jaouadi, W., & Naghmouchi, S. (2021). Climate change impacts on spatial

distribution, tree-ring growth, and water use of stone pine (Pinus pinea

L.) forests in the Mediterranean region and silvicultural practices to limit

those impacts. iForest- Biogeosciences and Forestry, 14(2),

104.

Mishra,

A. K., & Singh, V. P. (2010). A

review of drought concepts. Journal

of hydrology, 391(1-2), 202- 216.

Muñoz,

V. F. L., Delard, C., González, M. V. G., Mutke, S., & Díaz, V. C. F.

(2012). Introducción del pino piñonero

(Pinus pinea L.) en Chile. Ciencia

& Investigación Forestal, 18(2), 39-52.

Mutke,

S., Calama, R., González-Martínez, S. C., Montero, G., Javier Gordo, F., Bono,

D., & Gil, L. (2012). Mediterranean

stone pine: botany and horticulture. Horticultural

reviews, 39(1), 153-201.

Natalini,

F., Alejano, R., Vázquez-Piqué, J., Pardos, M., Calama, R., & Büntgen, U.

(2016). Spatiotemporal variability of

stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) growth response to climate across the

Iberian Peninsula. Dendrochronologia,

40, 72-84.

Natalini,

F., Alejano, R., Pardos, M., Calama, R., & Vázquez-Piqué, J. (2024). Declining trends in long-term Pinus pinea

L. growth forecasts in Southwestern Spain. Dendrochronologia, 88, 126252.

Navarro-Cerrillo,

R. M., Cachinero-Vivar, A. M., Pérez-Priego, Ó., Cantón, R. A., Begueria, S.,

& Camarero, J. J. (2023). Developing alternatives to adaptive silviculture:

Thinning and tree growth resistance to drought in a Pinus species on an

elevated gradient in Southern Spain. Forest Ecology and Management, 537,

120936.

Perulli,

G. D., Peters, R. L., von Arx, G., Grappadelli, L. C., Manfrini, L., &

Cherubini, P. (2019). Learning from the past to improve in the future:

tree-ring wood anatomy as retrospective tool to help orchard irrigation

management. In IX International Symposium on Irrigation of Horticultural

Crops 1335 (p. 179-188).

Piraino,

S. (2020). Assessing Pinus pinea L. resilience to three consecutive

droughts in central-western Italian Peninsula. iForest-Biogeosciences

and Forestry, 13(3), 246.

Piraino,

S., Camiz, S., Di Filippo, A., Piovesan, G., & Spada, F. (2013). A

dendrochronological analysis of Pinus pinea L. on the Italian

mid-Tyrrhenian coast. Geochronometria, 40, 77-89.

Piraino,

S., Cignoli, F. N., Robledo, S., & Pérez, S. (2021). Un pino mediterráneo

en Sudamérica: situación actual y potencialidad de Pinus pinea L. en

territorio argentino. Experticia, 12(1). 7-10. https://revistas.uncu.edu.ar/ojs3/index.php/experticia/article/view/5041

Piraino,

S., Molina, J. A., Hadad, M. A., & Roig, F. A. (2022). Resilience capacity

of Araucaria araucana to extreme drought events. Dendrochronologia,

75, 125996.

Piraino,

S., Hadad, M. A., Ribas‑Fernández,

Y. A., & Roig, F. A. (2024). Sex-dependent resilience to extreme drought

events: implications for climate change adaptation of a South American

endangered tree species. Ecological Processes, 13(1), 24.

Rigling,

A., Brühlhart, H., Bräker, O. U., Forster, T., & Schweingruber, F. H.

(2003). Effects of irrigation on diameter growth and vertical resin duct

production in Pinus sylvestris L. on dry sites in the central Alps,

Switzerland. Forest Ecology and Management, 175(1-3), 285-296.

Schulman,

E. (1956). Dendroclimatic changes in semiarid America. University of

Arizona.

Schwarz,

J., Skiadaresis, G., Kohler, M., Kunz, J., Schnabel, F., Vitali, V., &

Bauhus, J. (2020). Quantifying growth responses of trees to drought-A critique

of commonly used resilience indices and recommendations for future studies. Current

Forestry Reports, 6, 185-200.

Speer,

J. H. (2010). Fundamentals of tree-ring research. University of Arizona

Press.

Trouet,

V., & Van Oldenborgh, G. J. (2013). KNMI Climate Explorer: a

web-based research tool for high-resolution paleoclimatology. Tree-Ring

Research, 69(1), 3-13.

Vicente-Serrano,

S. M., Beguería, S., & López-Moreno, J. I. (2010). A multiscalar drought

index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation

evapotranspiration index. Journal of climate, 23(7), 1696-1718.

Villalba,

R., & Veblen, T. T. (1997). Spatial and temporal variation in Austrocedrus

growth along the forest steppe ecotone in northern Patagonia. Canadian

Journal of Forest Research, 27(4), 580-597.

Wigley,

T. M., Briffa, K. R., & Jones, P. D. (1984). On the average value of

correlated time series, with applications in dendroclimatology and

hydrometeorology. Journal of Applied Meteorology and climatology, 23(2),

201-213.