Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

First

Report of the Black Soybean Weevil Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler

(Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Córdoba, Argentina. Crop Damage Estimation

Primer

registro del picudo negro de la soja Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler

(Coleoptera: Curculionidae) en la provincia de Córdoba, Argentina, y estimación

de daño en el cultivo

Celso Roberto

Peralta1, 2, 3*,

Matías Rinero3,

Daniel Antonio

Igarzábal3,

Roberto Luis De

Rossi1

1Universidad

Católica de Córdoba. Avda. Armada Argentina N° 3555. C. P. X5016DHK. Córdoba.

Argentina.

2Universidad

Nacional de Córdoba. Ing. Agr. Félix Aldo Marrone 746. C. P. 5000. Córdoba.

Argentina.

3Moha

S. A. Calle Tucumán 255 Of 14. X5220BBE. Jesús María. Córdoba. Argentina.

*0424746@ucc.edu.ar

Abstract

The black

soybean weevil is an endemic pest in northwestern and northeastern Argentina,

causing significant damage. The objective of this study was to confirm the presence

of this species in Córdoba, describe symptomatology and evaluate the potential impact

on the crop. Surveys were conducted in plots located in the north-central part

of the province. Individuals were collected and a quantitative assessment of

symptoms and damage was conducted. Twenty compound samples were taken from

sectors showing different physiological appearances (green vs. yellowish).

In each group, total pod number and damaged pod number allowed calculating

damage percentage. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and Fisher's test (α = 0.05).

All collected individuals matched the morphological descriptions reported in

the literature for the species Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler. Green plants

had a higher proportion of damaged pods (0.89) and fewer pods (31.85) compared to

yellowish plants (0.53 and 46.65, respectively). This relationship suggests a

direct effect on biomass partitioning. Our finding remaps the pest’s

distribution range, warning areas of high agricultural production in Córdoba

and raising the need to link public-private actions to minimize its spread.

Keywords: damaged pods, yield

losses, distribution, Glycine max

Resumen

El picudo negro

de la soja es una plaga endémica en el norte de Argentina, donde genera daños

significativos. El objetivo del trabajo fue confirmar la presencia de esta

especie en Córdoba, describir los síntomas observados y evaluar el impacto

potencial sobre el cultivo. Se realizaron relevamientos en lotes del

centro-norte de la provincia, se recolectaron individuos y se realizó una

evaluación cuantitativa de los síntomas y daños. Se realizaron veinte muestreos

compuestos de cinco plantas cada una en sectores que presentaban plantas con distinto

aspecto fisiológico (verdes vs. amarillentas). En cada grupo se evaluó

el número total de vainas, el número de vainas dañadas, y se calculó el

porcentaje de daño, las diferencias registradas fueron analizadas mediante

ANOVA y sus medias diferenciadas por test de Fisher (α 0,05). Todos los

individuos recolectados coincidieron con las medidas morfológicas y descripciones

registradas en la literatura para la especie Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler.

Las plantas verdes presentaron mayor proporción de vainas dañadas (0,89) y

menor número total de vainas (31,85) en comparación con las amarillentas (0,53

y 46,65 respectivamente), con diferencias significativas (p< 0,05).

Esta relación sugiere un efecto directo del insecto sobre la fisiología del

cultivo, asociado con alteraciones en la relación fuente-destino. Este hallazgo

amplía el rango de distribución conocida de esta plaga, alertando sobre su

posible establecimiento en zonas de alta producción agrícola de Córdoba y

planteando la necesidad de vincular acciones público y privadas para minimizar

o contener la expansión de la plaga.

Palabras claves:

vainas

dañadas, pérdidas de rendimiento, distribución, Glycine max

Originales: Recepción: 20/05/2025 - Aceptación: 01/09/2025

Introduction

Soybean (Glycine

max L.) is a major pillar of agricultural production in Argentina. In Córdoba

Province, soybean occupies approximately 4,758,800

hectares, which represents 62% of the total summer crop area estimated at

7,668,200 hectares (Bolsa de Cereales de Córdoba, 2024). In this

context, phytosanitary monitoring has gained importance due to the emergence

and spread of pests holding significant agronomic impact.

Until recently,

the phytosanitary status of soybean in Córdoba remained relatively stable, with

a pest complex dominated by well-known, routinely monitored species. However,

in recent seasons, isolated insects, rarely found in the region, have been

recorded. Some lack clear antecedents as pests in the local production system (Peralta,

2022).

The genus Rhyssomatus

Schönherr (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) comprises South American native

species, several of which are associated with legume crops (Wibmer

& O’Brien, 1986; Lanteri et al., 2002). In

north-western Argentina (NOA), the weevil complex associated with soybean

constitutes an important phytosanitary problem, given direct damage and rapid

dispersal capacity. Within this group, Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler,

known as the soybean black weevil, has become a major pest in the region due to

its high biotic potential, its impact on reproductive structures and its

adaptation to different environments (Socías et al.,

2009; Cazado et al., 2014).

In recent years,

its presence has been documented in new expansion zones in north-west Argentina

(NOA) like eastern Santiago del Estero, on soybean and cotton crops (Casuso

et al., 2022).

R. subtilis shows a strong association with cultivated and volunteer legumes

and is characterized by ovipositing in soybean pods, where larvae feed on the

seeds, hindering early detection, and causing direct yield losses (Cazado

et al., 2014).

Confirmation of the presence of R. subtilis in soybean fields of

north-central Córdoba would not only imply an expansion of its geographic range

but also serve as a warning for phytosanitary surveillance systems in the

Pampas region.

This work aimed

to document the presence of R. subtilis in soybean crops in Córdoba Province,

describe field symptomatology, assess damage level and discuss potential agronomic,

ecological, and productive implications.

Materials

and Methods

Sampling

Sites

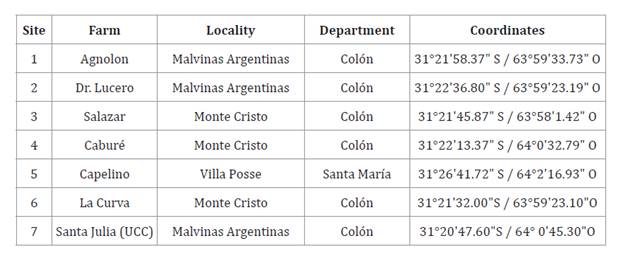

During the

2024/25 growing season, seven sites located in north-center Córdoba, within

Colón and Santa María Departments, were visited following grower reports of pod

damage. All sites were at advanced reproductive stages (R6-R7), (Fehr

& Caviness, 1977)

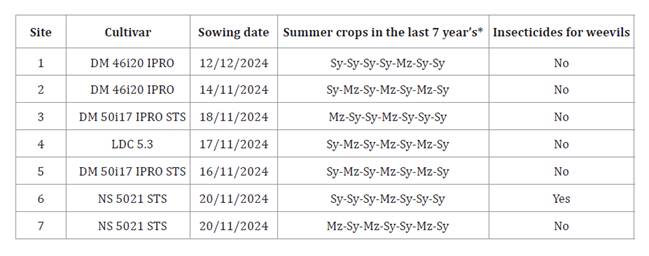

when sampled (table 1).

Table

1. Sampling sites for detection of the

soybean black weevil (Rhyssomatus subtilis) located in the north-center

of Córdoba Province, 2024/25 growing season.

Tabla 1. Sitios

de muestreo en el centro-norte de la provincia de Córdoba, campaña agrícola

2024-25, para la determinación de la presencia del picudo negro de la soja (Rhyssomatus

subtilis).

Field

Characteristics and Management

All seven sites

were commercial soybean fields under no-tillage. Only one site had received a

specific insecticide spray targeting curculionids. Previous summer-crop

rotations differed among fields (table 2). Additionally,

a comparative map showed historical phytosanitary monitoring sites in

north-central Córdoba and the sites where R. subtilis was detected in

2024/25. The historical database (15 seasons, 2009/10-2024/25) was generated by

Moha S. A. (firm to which the authors belong). These data were overlaid with

the 2024/25 detection sites.

Table

2. Crop management indicators of seven

soybean fields showing pod damage caused by the black weevil (Rhyssomatus

subtilis), Córdoba, 2024/25.

Tabla 2. Detalle

de manejo de cultivo de siete lotes de producción de soja con presencia de daño

de picudo negro (Rhyssomatus subtilis) en vainas. Córdoba, campaña

agrícola 2024-25.

* Sy.: Soybean; Mz.: Maize.

Date,

Plot Segmentation and Sampling Procedure

Damage

assessment was carried out on April 2, 2025 at Site 1 (Agnolon Farm), with the

crop at advanced R6 (Fehr & Caviness, 1971). At the

remaining sites (2-7), samples of adult weevils, damaged pods and other affected

plant structures were collected for morphological identification.

At Site 1,

structured damage evaluation was performed by random sampling within two

contrasting areas of the field: (i) zones with naturally yellowing plants

(considered slightly damaged) and (ii) zones with completely green plants

(considered severely damaged). At each zone, 20 composite samples were taken,

each composed of five consecutive plants manually removed along the sowing row.

Plants were transported to the laboratory, where all pods per sample were

removed and counted. Total pod number and damaged pod number (attributable to R.

subtilis) were recorded, allowing estimation of relative incidence. Pod set

differences among areas and percentage of damaged pods were calculated in each

site. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD test (α < 0.05) were performed using InfoStat

statistical software (Di Rienzo et al., 2010).

At Sites 2-7,

only adult curculionids, damaged pods and other affected tissues were

collected. Samples were kept in ventilated glass containers and taken to the

laboratory for taxonomic confirmation. Photographic records of damage were

obtained with a compact digital camera (Olympus Tough TG-4 iHS, Sony ZV-1) and

a DJI Mavic Pro drone. Drone images were acquired with stacked exposures to

enhance contrast. Chromatic classification of RGB channels was performed using

color-histogram thresholds and digital-image analysis tools in Python.

Classified zones were delineated by contour detection for visual and quantitative

comparison. Color interpretation was based on field observations of symptoms

like foliage persistence, green pods, and adult presence.

Insect

Identification

The collected

specimens were morphologically identified in the laboratory with binocular

magnifying glass and using taxonomic keys Fiedler

(1937-1938).

Results

Insect

Identification

All collected

individuals matched the descriptions recorded for Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler

(Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (Fiedler,

1937-1938; Socías et al., 2009; Cazado et al., 2014). The finding

was reported to Servicio Nacional de Sanidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria (SENASA)

through the Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia y Monitoreo de plagas (SINAVIMO)

(communication No. 1368) on April 12, 2025.

Córdoba

specimens were identified based on the original characters of Fiedler (1939)

and the morphological syntheses of Socías et al.

(2009)

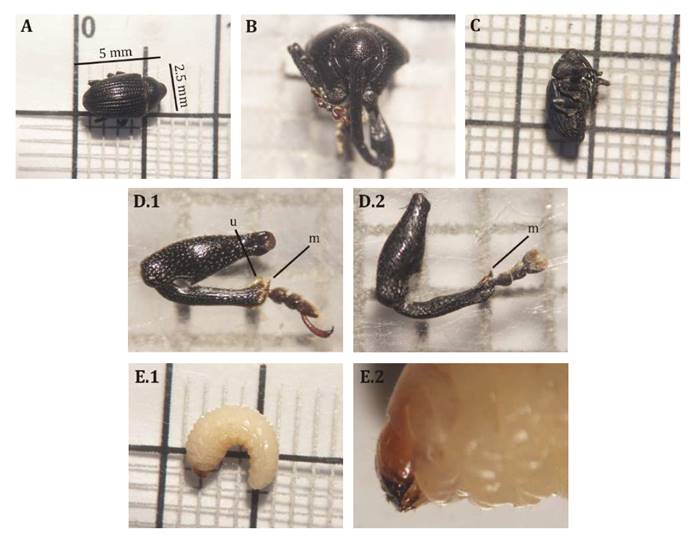

and Cazado et al. (2014): (I) length

4.8-5.2 mm, width 2.5-3 mm, body oval-elongate, somewhat sub-rhombic; (II)

integument dark brown-black, lacking scales or bands; (III) head very finely

and densely punctate, strongly arched, the eyes separated dorsally by more than

the width of the rostrum; (IV) rostrum very slender, moderately curved,

considerably longer than the head and pronotum, recessed at the base so that

the head and the base of the rostrum are not aligned in profile; (V) elytra

with longitudinal striae and well-marked rows of punctures; (VI) female fore

leg with a weak, angulate femur and the presence of an uncus (u) and mucro (m)

on the tibia; (VII) apodous larvae 5-6 mm long, body curved in a “C” shape,

milky white, with a light-brown to caramel head (figure 1).

A) adult dimensions and

color details; B) frontal view of the head, its punctures and eyes separated

above the rostrum; C) adult lateral view; D.1) detail of female fore legs with

presence of uncus (u) and mucro; D.2) detail of male fore legs only with

presence of mucro; E.1) lateral view of apodous larva with curved body; E.2)

lateral view of head in apodous larva.

A) dimensiones y detalles

de color de adulto; B) vista frontal de cabeza, sus puntuaciones y ojos

separados por encima de la probóscide; C) adulto vista lateral; D.1) detalle de

patas delanteras de hembra con presencia de uncus (u) y mucro; D.2) detalle de

patas delanteras de macho solo con presencia de mucro; E.1) vista lateral de

larva ápoda con cuerpo curvado; E.2) vista lateral de la cabeza en larva ápoda.

Figure 1. Rhyssomatus

subtilis adults and

larvae.

Figura 1. Adultos

y larvas de Rhyssomatus subtilis.

Sampling

Adults, larvae,

eggs, and soybean crop damage matched the literature describing R. subtilis at

the seven evaluated sites (figure 2).

A) Adult, B) Larva, C) Egg.

A) Adulto, B) Larva, C) Huevo.

Figure 2. Details

of Rhyssomatus subtilis specimens found in north-central Córdoba during

the 2024-25 growing season.

Figura 2. Detalle

de especímenes de Rhyssomatus subtilis encontrados en el centro-norte de

Córdoba durante la campaña agrícola 2024-25.

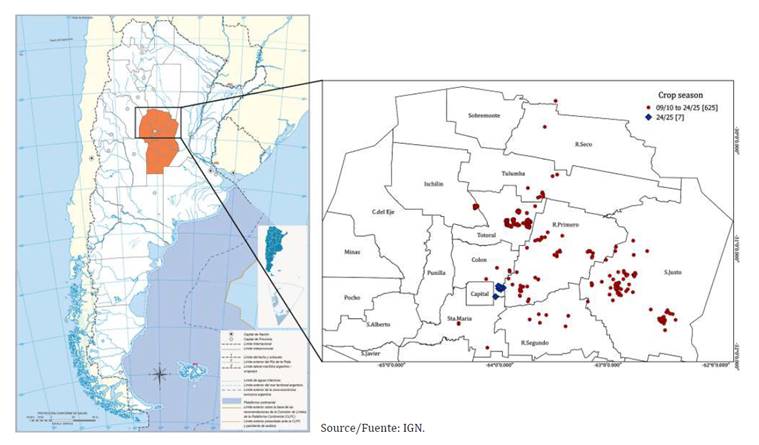

Considering

historical phytosanitary monitoring points previously surveyed by Moha S.A.

over 15 growing seasons, and the seven sites where we detected R. subtilis during

the 2024/25 season, the geographical distribution of the new detections is

shown in relation to previously pest-free areas (figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparative

map between historical phytosanitary monitoring sites (2009-10 to 2024-25)

surveyed by Moha S.A. (red circles) and sites with detection of Rhyssomatus

subtilis during the 2024/25 season (blue diamonds), showing the location of

the new detections in relation to previously monitored areas with no pest

records.

Figura 3. Mapa

comparativo entre sitios históricos de monitoreo fitosanitario (2009-10 a

2024-25) realizados por la consultora Moha S.A. (círculos rojos) y los sitios

con detección de Rhyssomatus subtilis durante la campaña 2024/25 (rombos

azules), donde se denota la localización de las nuevas detecciones en relación

con las áreas previamente monitoreadas sin registro de la plaga.

Damage

Assessment

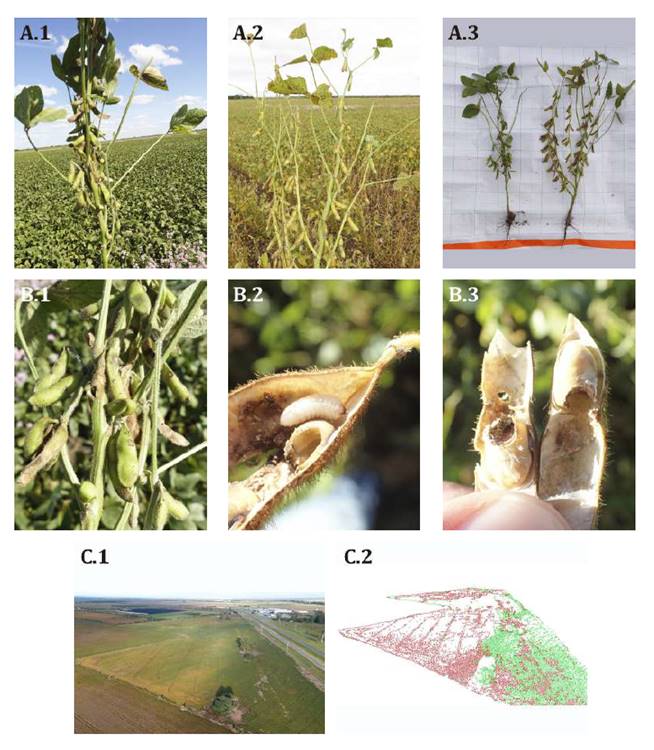

At Site 1,

plants with contrasting physiological appearances revealed significant

differences regarding proportion of damaged pods and total number of pods per

plant (figure

4).

A.1, A.2, A.3) Plants with different behavior (green

vs. yellowing); B.1, B.2, B.3) detail of affected pods; C.1) drone image

of the field with high infestation in Malvinas Argentinas, Córdoba, showing

sectors with yellowing and green plants; C.2) image of the same field produced

through chromatic classification based on the assessments performed, In red,

sectors with lower infestation (yellowing plants due to natural senescence) and

in green, sectors with higher infestation (green plants with foliage

retention).

A.1, A.2, A.3) Plantas con distintos comportamientos

(verdes vs. amarillentas); B.1, B.2) detalle de vainas afectadas; C.1) Imagen

aérea (drone) del lote con alta afección en la localidad de Malvinas

Argentinas, Córdoba, donde se visualizan sectores con plantas amarillentas y

plantas verdes; C.2) Imagen de ese lote realizada con clasificación cromática

con base en las evaluaciones realizadas, siendo el color rojo la representación

de sectores con menor afección (plantas amarillentas por senescencia natural) y

en verde los sectores con mayor afección (plantas verdes con retención foliar).

Figure 4. Damage

recorded by Rhyssomatus subtilis in north-central Córdoba during the

2024-2025 growing season.

Figura 4. Detalle

de los daños registrados por Rhyssomatus subtilis en el centro-norte de

Córdoba durante la campaña agrícola 2024-2025.

Damage

percentage was significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in green plants (0.89 ±

0.01) than in yellowing plants (0.53 ± 0.01). The CV was 9.04 %, and the

adjusted R² was 0.89, indicating modeling high explanatory power. Likewise,

total number of pods differed significantly (p = 0.0015), averaging 46.65 ±

3.05 pods in yellowing plants versus 31.85 ± 3.05 in green plants. These

results indicate a strong association between damage intensity and plant

physiological status, suggesting that R. subtilis may be affecting both

pod number and pod integrity at crop advanced reproductive stages.

At the remaining

sites (2-7), although quantitative assessments were not conducted, damage was

observed at varying degrees of severity. In all cases, adults were found on

plants and damaged pods, together with signs of integument perforation, injured

seeds, and R. subtilis larvae feeding (figure 4).

Discussion

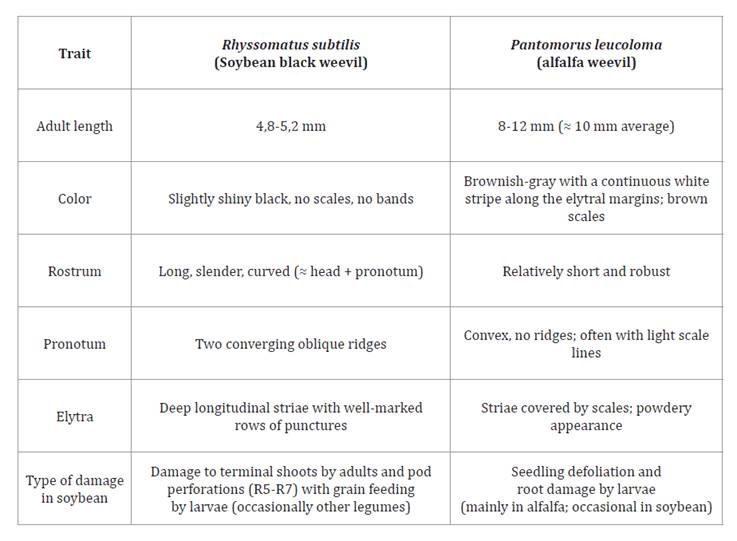

Confirmation of R.

subtilis Fiedler in the Colón and Santa María Departments of Córdoba

extends its geographic distribution towards center Argentina by approximately

450 km with respect to historical reports from NOA (Salta, Tucumán and Santiago

del Estero). The species has been verified in more than 53 localities in that

region (Cazado et al., 2014), with these

new determinations confirming a significant latitudinal dispersal capacity,

colonizing new soybean areas of the Chaco ecoregion.

The adults

sampled from north-central Córdoba exhibited cited characters (Socías

et al., 2009; Cazado et al., 2014), ruling out

possible confusion with other local curculionid species of wider regional

distribution like Pantomorus leucoloma (Aragón, 2007) (table

3).

Table

3. Comparative table of morphological

traits of soybean black weevil (Rhyssomatus subtilis) and alfalfa weevil

(Pantomorus leucoloma).

Tabla 3. Tabla

comparativa de características morfológicas para la diferenciación entre el

Picudo negro de la soja (Rhyssomatus subtilis) y el Gorgojo de la

alfalfa (Pantomorus leucoloma).

In the NOA

region, yield losses of up to 100% have been documented under high, uncontrolled

populations of R. subtilis. In the grain-filling reproductive phase (R5

to R6)- a critical stage-losses can reach 60% (Cazado et al.,

2014).

In eastern Santiago del Estero Province, pod damage ranges between 21% and 42%

(Casuso

et al., 2023).

Site 1 showed

that plants with the highest proportion of damaged pods, approximately 90%

attributable to R. subtilis, displayed an active vegetative state

(green). In contrast, less damaged plants, 53% damaged pods, exhibited a normal

progression of crop senescence (yellowing), coinciding with previous studies (Cazado

et al., 2014; Casuso et al., 2023).

Different physiological

maturity among plants with greater damage suggests that affected reproductive

structures may have altered biomass partitioning, generating stem greening and

vegetative-tissue retention as a compensatory response to physiological

imbalance.

This behavior

partly resembles the green stem syndrome (GSS) in soybeans, characterized by

persistent green tissues at harvest, linked to physiological imbalances in

assimilate redistribution, abiotic stress, insect or disease damage, and even

management practices (Rotundo et al., 2012;

Salvagiotti et al., 2020). Particularly, the loss of sink

structures like pods or seeds can result in sugar accumulation in vegetative

tissues, delaying maturity and provoking symptoms like GSS (Egli

& Bruening, 2006).

A similar

situation occurs in the so-called “soja loca” (“crazy soybean”) syndrome,

reported mainly in Brazil and northern Argentina, where prolonged leaf

retention, green stems and pod abortion have also been associated with

infections by the nematode Aphelenchoides besseyi and hormonal

alterations (Ferreira et al., 2010). Although

nematodes were not detected in our study, symptoms shared some

eco-physiological patterns like the loss of reproductive structures and the

persistence of active vegetative tissues. This reinforces the need to broaden

entomological and eco-physiological monitoring.

Larval activity

caused direct seed loss and partitioning alterations, leading to physiological

imbalances like those described in the green stem and/or crazy soybean

syndromes. These effects compromise yield and hinder visual assessment of

phenological progress, generating risks in harvest scheduling.

To date, no

documented records of R. subtilis existed for Córdoba Province. This

finding becomes invaluable from agronomic, sanitary, and ecological

perspectives, marking a significant expansion in the known geographic

distribution of this pest in Argentina. We highlight the need to adapt monitoring

schemes within regional phytosanitary surveillance systems to facilitate timely

detection of R. subtilis, and advance local studies assessing population

behavior, crop-pest interactions and possible integrated management strategies.

Conclusions

For the first

time, the presence of the soybean black weevil R. subtilis was confirmed

in fields of Córdoba Province.

Physiological

differences were observed among plants with different levels of damage, linked

to the intensity of the infestation.

The productive

sector of Córdoba is on alert due to the presence of a new pest with high

damage potential. Public-private actions should minimize pest spread.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks

to the Agricultural Engineers Hugo Digón, Eduardo Vasallo and Daniela Vecchio

for their contributions on sites where the pest is present and their very

useful comments. Thanks also to the producers Fabián Daga and Rolando Carando

for facilitating access and collaborating in the survey.

References

Aragón,

J. & Imwinkelried, JM. (2007). Manejo integrado de plagas de la alfalfa. En

DH Basigalup (Ed.), El cultivo de la alfalfa en la Argentina, (p.

165-197). Ediciones INTA - EEA Manfredi.

Bolsa

de Cereales de Córdoba. (2024). Informe de campaña agrícola 2023/2024.

https://www.bccba. org.ar

Casuso,

M., Tarragó, J., Cazado, L., Casmuz, A., Cancino, C., Soneira, D., &

Gullini, L. (2022). Registro de Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler

(Coleoptera: Curculionidae) en la zona de El Caburé (Santiago del Estero) sobre

los cultivos de soja Glycine max (L.) Merr. y

algodón (Gossypium hirsutum). INTA Las Breñas.

Casuso,

VM, Cancino, CA, Tarragó, JR, & Pérez, GA (2023). Primeras evaluaciones

para conocer el comportamiento del picudo negro de la soja Rhyssomatus

subtilis Fiedler (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) en el este de Santiago del

Estero. En XXVIII Reunión de Comunicaciones Científicas, Técnicas y de

Extensión. Universidad Nacional del Nordeste, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. p.

38. https://repositorio.unne.edu.ar/handle/123456789/55928

Cazado,

LE, Casmuz, AS, Scalora, F., Murúa, MG, Socías, MG, Gastaminza, GA, &

Willink, E. (2014). El picudo negro de la soja, Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler

(Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Avance Agroindustrial, 35(4), 55-60.

Di

Rienzo, JA, Balzarini, M., Casanoves, F., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., Robledo,

CW. (2010). InfoStat, Software Estadístico. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba,

Argentina.

Egli,

DB, & Bruening, WP. (2006). Depodding causes green-stem syndrome in

soybean. Crop Management, 5(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1094/CM-2006-0104-01-RS

Fehr,

WR, & Caviness, CE. (1977). Stages of soybean development (Special Report

N° 80). Iowa State University Cooperative Extension Service.

Ferreira,

AB, de Almeida, MR, & Dias, WP. (2010). Incidência de Aphelenchoides

besseyi em cultivares de soja com sintomas de “soja louca”. Nematologia

Brasileira, 34(1), 39-45.

Fiedler,

C. (1937-1938). Neue südamerikanische Arten der Gattung Rhyssomatus Schönh.

(Col. Curc. Chryptorhynch.). Entomologisches Nachrichtenblatt (Troppau), 12:

81-96.

Lanteri,

AA, del Río, MG, & Marvaldi, AE. (2002). Curculionoidea (Coleoptera). In LE

Claps, J. Morrone & MC Roig-Juñent (Eds.), Biodiversidad de artrópodos

argentinos, 1: 327-349. Ediciones Sur.

Peralta,

CR. (2022). Congreso N°30 AAPRESID: Un congreso a suelo abierto. Tecnologías

para el manejo integrado de insectos.

Rotundo,

JL, Salvagiotti, F., & Andrade, FH. (2012). Physiological and management

causes of the green stem disorder in soybean. Field Crops Research, 134:

186-195.

Salvagiotti,

F., Rotundo, JL, & Pereyra, VR. (2020). Advances in understanding the green

stem disorder in soybean. Revista de la Facultad de Agronomía, 119(1),

1-9.

Socías,

MG, Rosado-Neto, GH, Casmuz, AS, Zaia, DG, & Willink, E. (2009). Rhyssomatus

subtilis Fiedler (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), primer registro para la

Argentina y primera cita de planta hospedera, Glycine max (L) Merr. Revista

Industrial y Agrícola de Tucumán, 86(1): 43-46.

Wibmer,

GJ, & O’Brien, CW. (1986). Annotated checklist of the weevils (Curculionidae

sensu lato) of South America. Memoirs of the American Entomological

Institute, 39: 1-563.