Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. En prensa. ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Original article

Social

Welfare Effects of Water Security Improvements in Arid Regions: The Case of

Mendoza, Argentina

Efectos

sobre el bienestar social de mejoras en la seguridad hídrica en regiones

áridas: el caso de Mendoza, Argentina

Verónica Inés Farreras González1, 2*,

Carolina Lauro1,

Laura Abraham3,

Pablo Federico Salvador2

1Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias

Ambientales (CCT-CONICET-Mendoza). Av. Ruiz Leal s/n. Parque General San

Martín. 5500 Mendoza. Argentina.

2Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas.

M5502JMA. Mendoza. Argentina.

3Universidad

Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Cátedra de Administración

Rural. Almirante Brown 500. M5528AHB. Chacras de Coria. Mendoza. Argentina.

*vfarreras@mendoza-conicet.gob.ar

Abstract

Water security is a

critical challenge in Mendoza, Argentina, an arid region that faces rising

water demand and uncertainty caused by climate change. Agriculture consumes 90%

of the fresh water in the region, while vineyards occupy just over 60% of the

cultivated area. This study estimates the social welfare effects of an

improvement in water security achieved by reallocating water from vineyards to

other uses. We used a multidisciplinary approach, applying benefit transfer to

estimate social welfare changes and water footprint to quantify shifts in water

availability. Our findings suggest that a water security policy in the

Mendocinian Northern Oasis can result in an average 21-percentage-point

increase in annual water availability for other uses. This equals an average

household welfare gain of 17.43 US dollars per year (95% CI: 8.40-35.64) at

2024 prices over the next 30 years. This study offers a framework for regions

worldwide facing similar challenges of water scarcity, increasing water demand,

and climate change. Moreover, it can support the design of more informed water

management strategies to ensure long-term water security.

Keywords: water security,

social welfare, benefit transfer method, water footprint, water reallocation,

arid regions, mendocinian northern oasis

Resumen

La seguridad

hídrica es un desafío crítico en Mendoza, Argentina, una región árida que

enfrenta una creciente demanda de agua y la incertidumbre generada por el

cambio climático. La agricultura consume el 90% del agua dulce mientras que los

viñedos ocupan más del 60% de la superficie cultivada. Este estudio estima los

efectos sobre el bienestar social de una mejora en la seguridad hídrica

mediante la reasignación de agua de viñedos a otros usos. Aplicamos un enfoque

multidisciplinario, usando transferencia de beneficios para estimar cambios en

el bienestar social y la huella hídrica para cuantificar variaciones en la

disponibilidad de agua. Nuestros resultados sugieren que una política de

seguridad hídrica en el Oasis Norte Mendocino puede generar un aumento promedio

de 21 puntos porcentuales en la disponibilidad anual de agua para otros usos,

lo que equivale a una ganancia anual promedio en bienestar de 17,43 USD por

hogar (IC 95%: 8,40-35,64), a precios de 2024, durante los próximos 30 años.

Este estudio ofrece un marco replicable en otras regiones con desafíos

similares de escasez y creciente demanda hídrica, contribuyendo al diseño de

estrategias de gestión del agua más informadas para garantizar la seguridad

hídrica a largo plazo.

Palabras claves: seguridad hídrica,

bienestar social, método de la transferencia de beneficios, huella hídrica,

reasignación del agua, regiones áridas, oasis norte de Mendoza

Originales: Recepción: 03/06/2025-

Aceptación: 26/09/2025

Introduction

On the eastern side

of the Central Andes, mountain rivers flow through the Mendocinian landscapes,

providing vital water resources to the region. As population and urban growth

accelerate in an area where water demand is increasing, climate change is

introducing greater uncertainty and variability in water availability (Lauro et al., 2022). If climate models prove

accurate and current water management policies remain unchanged, Mendoza -a

historically arid region- may become even drier in coming decades (Rivera et al., 2020). This scenario could

exacerbate existing water scarcity, intensifying current challenges and

threatening human welfare.

Currently,

agriculture consumes approximately 90% of the fresh water in Mendoza (Duek, 2018). In this context, ensuring secure, sustainable

and profitable food production while conserving water for alternative uses,

including environmental preservation, requires improvements in agricultural

water management efficiency (Pérez Blanco et al.,

2020).

In response, recent

efforts in Mendoza have focused on aligning water distribution with crop water

requirements to improve water management efficiency (Villodas

et al., 2023). However, previous studies, such as that of Morábito et al. (2005), had already addressed

key aspects of this issue. Such efforts could enhance water security by

conserving agricultural water to reallocate to other uses, potentially

improving social welfare. However, the implications of these strategies for

Mendocinian citizens’ welfare remain unclear.

Understanding the

social welfare effects of water security management can provide crucial

insights. For instance, if society were to intervene to enhance water security,

what would be the maximum it would invest in water systems matching crop

requirements? Alternatively, what economic compensation might society consider

offering if the reforms necessary to achieve water security result in

unintended consequences for certain users? Addressing these questions

highlights the importance of economic valuation in public policy decisions.

Economic valuation

is widely applied to estimate the monetary value of changes in people’s welfare

resulting from ecological or environmental shifts (Carson

et al., 1993). However, to our knowledge, this approach has not been

applied to assess how changes in water security -through increased water

availability and reallocation- affect welfare. The closest studies have

addressed the economic valuation of certain aspects of water security, the role

of prices in managing water scarcity, and governance issues (Farreras et al., 2017; Farreras and Abraham, 2020;

Katz, 2016; Pellegrini et al., 2023; Pérez Blanco et al., 2020

and Zetland, 2021). Other related studies examine overexploitation, demand

quantification for various uses, and the impacts of climate variability on

water supply (Castex et al., 2015; Konapala et

al., 2020; Lauro et al., 2021; Rivera et al., 2021).

Motivated by the

importance of economic valuation in decision-making, our study combines

economic and hydrological data from 2010 to 2020 in a case study. Our main aim

is to estimate the changes in citizens’ welfare in the Mendocinian Northern

Oasis due to improved water security. This improvement comes from reallocating

water from vineyards -which cover just over 60% of the cultivated area- to

industry, municipal areas, and non-viticultural crops. These changes are

achieved while maintaining or even increasing grapevine production. The

percentage of water allocated for the population is not included within the

percentage of water available to other uses. This is because Mendoza Water Law

1884, which remains in effect, prioritises water supply for the population over

other uses (DGI, 2016b).

This study provides

a framework for regions worldwide facing similar water scarcity challenges. By

assessing social welfare effects of an improvement in water security, it offers

critical insights for decision-makers, policymakers, and resource managers in

comparable global contexts. These insights support the design of more informed

water management strategies, ensuring long-term water security.

Materials

and Methods

Study

Area

Because of the

region’s dry climate, most agricultural and urban areas in Mendoza are confined

to small parts of the territory. These oases were established using an

irrigation system of ditches and canals that carefully follows the topography

of the region. This system makes the most of the water coming from mountain

rivers, whose streamflow is the result of melting snow and Andean glaciers. It

is also supported by groundwater boreholes (Monnet et

al., 2022; Morábito et al., 2007). In Mendoza, the irrigation

water is managed as a common resource through political and collective

processes. Therefore, long-term water security depends on strong institutions

and deep reforms (Zetland, 2021).

Between 2010 and

2020, mountain rivers in Mendoza experienced a significant hydrological deficit

due to reduced snowfall associated with climate variability and climate change

(Rivera et al., 2021). Under different global

warming scenarios, climate projections for components of the hydrological cycle

in the Central Andes indicate further reductions in snowfall and river flows.

These effects will undoubtedly impact the availability of water resources,

highlighting the need for efficient water use (Castex et

al., 2015; Rivera et al., 2020).

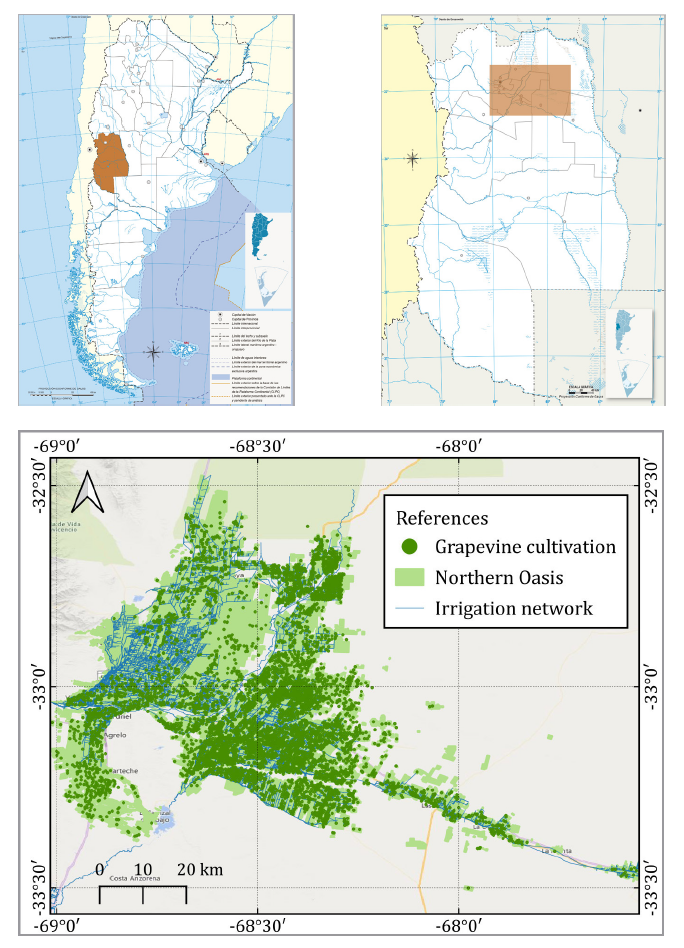

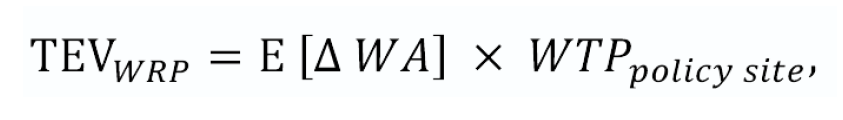

Our area of study,

the Mendocinian Northern Oasis irrigated by the Mendoza and Tunuyán Inferior

Rivers, is home to more than half of the province’s total population (figure 1). This region is characterised by an arid and semi-arid

climate. The average annual minimum and maximum temperatures are 11°C and 23°C,

respectively, with an annual rainfall of 267 mm (SMN,

2024). The soils are classified as typical Torrifluvents with a loamy

texture (INTA, 1990).

Source:

Own elaboration based on data from the National Sanitary Registry of

Agricultural Products (RENSPA), the Territorial Environmental Information

System (SIAT), and the National Geographic Institute (IGN).

Fuente:

Elaboración propia basada en datos del Registro Nacional Sanitario de

Productores Agropecuarios (RENSPA), el Sistema de Información Ambiental

Territorial (SIAT) y el Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN).

Figure

1. Farm units with grapevine cultivation in the

Mendocinian Northern Oasis.

Figura

1. Explotaciones agropecuarias con

cultivo de vid en el Oasis Norte de Mendoza.

Although

agricultural landscapes exhibit considerable crop diversity, grapevine crops -Vitis

vinifera- are predominant, covering just over 60% of the cultivated area (INDEC, 2018). Among the diverse grape varieties grown,

three dominate nearly 50% of the vineyards: Malbec (22.36%), Bonarda (11.75%),

and Cereza (11.50%). The average annual grape production between 2008 and 2017

was approximately 1.1 million tonnes (INV, 2020).

Given the extensive area of vineyards in the oasis, the

efficient use of water is crucial. However, around 75% of grape-growing farms

rely on surface irrigation systems, one of the least water-efficient methods

compared to pressurised systems (INDEC, 2018).

Furthermore, the water distribution system disregards crop-specific

requirements, delivering the same amount of water per hectare regardless of

actual needs. Consequently, regional challenges related to water scarcity are

further exacerbated by current management, increasing uncertainty in the

availability at the oasis level and hindering efficient allocation. This

underscores the need for sustainable and efficient water management to ensure

long-term water security.

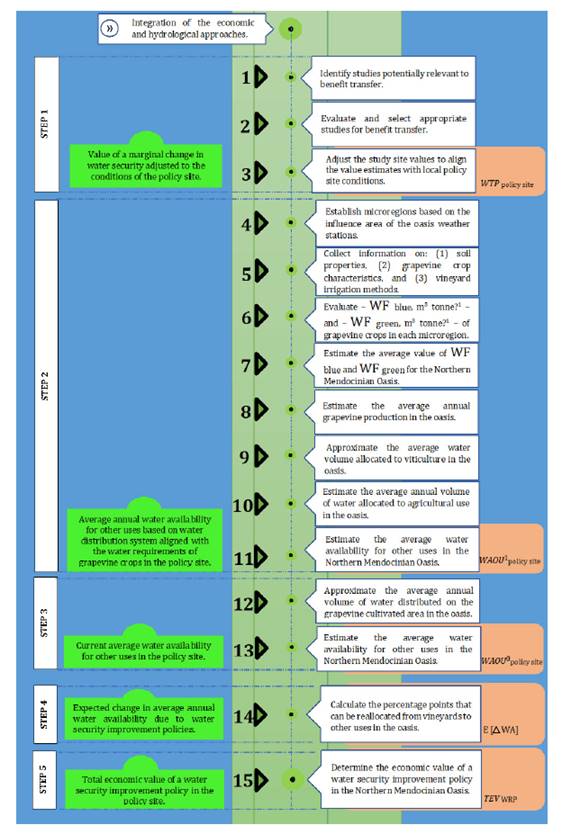

In this study, we adopted a multidisciplinary approach. The

benefit transfer method (BTM), widely used in the field of economics, was

applied to extrapolate values obtained from a previous study site to a policy

site. These values were used to predict welfare changes in the Mendocinian Northern

Oasis under water security policies that would reallocate agricultural water to

other uses. Additionally, a hydrological approach -specifically, the water

footprint (WF) methodology proposed by Hoekstra et

al. (2011)- was employed to estimate changes in water availability for

these alternative uses. This integrated approach, used to estimate the total

economic value (TEV) of a water security improvement policy, is summarised

below and illustrated in figure 2.

Source:

Own elaboration.

Fuente:

Elaboración propia.

Figure

2. Methodological framework integrating economic and

hydrological approaches to estimate the TEV of a water security improvement

policy.

Figura

2. Esquema metodológico que combina

enfoques económico e hidrológico para estimar el valor económico total de una

política de mejora de la seguridad hídrica.

First,

we identified potential study sites to infer the change in citizens’ welfare in

the Mendocinian Northern Oasis resulting from a water security improvement

policy. Since welfare is assumed to derive from the preferences satisfaction,

it can be quantified using the willingness to pay (WTP). To enhance welfare

change prediction accuracy, we adjusted the estimated WTP at the study site to

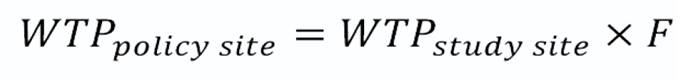

align with the policy site conditions. The process is formally outlined as

follows:

Where WPTpolicy site represents the value

of a marginal change in water security -achieved through a policy that

conserves agricultural water for reallocation to other uses- adjusted to the

policy site’s conditions. WPTstudy

site refers

to the value of a water security change estimated in one or more previous

studies, which requires adjustment. F, the adjustment factor, accounts for

these differences.

Factor 𝐹 may represent different types of adjustments, depending on the similarity between the study and the policy sites. The degree of similarity

is crucial in determining both the extent and the nature of these adjustments (Boutwell and Westra, 2013; Johnston et al., 2021).

Second, we

calculated the average annual water availability for other uses (WAOU 1study

site). This calculation was based on the water

distribution system aligned with the water requirements of grapevine crops in

the Mendocinian Northern Oasis. To achieve this, we first estimated the WF of

grapevine crops and determined the required volume of water according to their

specific needs. The steps involved in this estimation are outlined below.

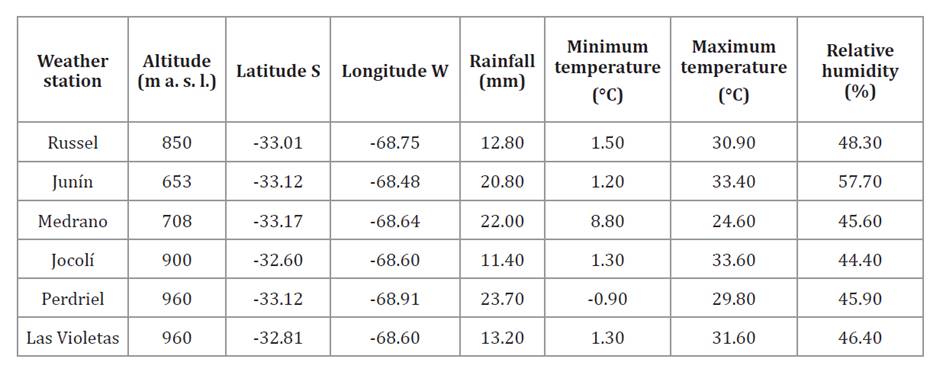

Initially, specific

data on rainfall, minimum and maximum temperatures, and relative humidity were

collected from six weather stations in the Mendocinian Northern Oasis

(2010-2020). Then, we used these data to divide the oasis into six climatic

microregions based on each station’s influence area. As a result, each

microregion retains the name of its corresponding weather station.

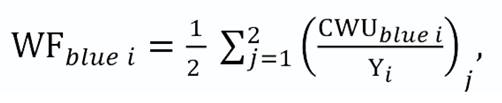

The WF is an

environmental indicator that accounts for the average volume of water required

according to the water needs of crops, expressed per unit of product, i.e.,

volume per unit of mass (m3 tonne-1).

The WF is

calculated as the ratio between the volume of crop water use (CWU, m3

ha-1)

throughout the entire crop growth period -from sprouting to harvest- and crop

yield (Y, tonne ha-1).

The CWU is the volume of water required to compensate for a crop’s

evapotranspiration losses and to prevent crop water stress. This CWU can be

divided into two components: the blue CWU -irrigation water- and the green CWU-

effective rain.

For this research,

we estimated the blue CWU (CWUblue,

m3 ha-1)

and the green CWU (CWUgreen,

m3 ha-1)

for each of the six microregions. The green and blue CWU were calculated from

the accumulation of daily evapotranspiration (ET, mm day-1)

during the growing period, from sprouting to harvest. To perform these

estimations, we used the CROPWAT program (FAO, 2024).

For this, we incorporated meteorological data (table 1),

grapevine crop parameters (Allen et al., 1998;

Civit et al., 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2000), and sandy loam

soil properties estimated with the Soil Water Characteristics software (USDA, 2024).

Table 1. Location

of weather stations and average meteorological data (2010-2020).

Tabla

1. Ubicación de las estaciones

meteorológicas y datos promedio (2010-2020).

Source:

Own elaboration based on data from the Agriculture and Climate Contingencies

Agency (DACC, 2021) of Mendoza province.

Fuente:

Elaboración propia basada en datos de la Dirección de Agricultura y

Contingencias Climáticas (DACC,

2021) de la provincia de Mendoza.

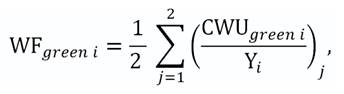

Using

the blue and green CWU values for each of the six microregions, the specific

blue and green WF of vineyards at the microregion level was inferred separately

from Equations (2) and (3), respectively.

Where WFblue i represents the average

blue WF in the i-th microregion, taking into account both surface and

pressurised irrigation systems; CWUblue i is the blue

CWU in the i-th microregion; Yi is the yield per hectare in the i-th microregion;

and j is the irrigation method, ranging from 1 to 2 (specifying, j = 1

surface and j =2 pressurised irrigation systems). The distinction in the

irrigation systems was considered using various crop coefficients (Kc) to

account for the differences in water requirements between surface (j =

1) and pressurised (j = 2) irrigation methods.

Where

WFgreen i represents the average green WF in the i-th

microregion, taking into account both surface and pressurised irrigation

systems; CWUgreen i is the green CWU in the i-th

microregion; Yi is the yield per hectare in the i-th

microregion; and j is the irrigation method, ranging from 1 to 2 (specifying, j

= 1surface and j =2 pressurised irrigation systems).

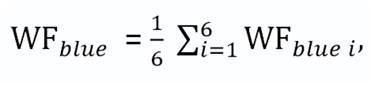

Then, the average values for both the blue and green WF were

calculated at the oasis level, formally:

Where

WFblue represents the average blue WF at oasis level; WFblue

i the blue WF in the i-th microregion; and i the

microregion, ranging from 1 to 6. Each i represents a distinct

microregion within the oasis.

Where

WFgreen represents the average green WF at oasis level; WFgreen

i the green WF in the i-th microregion; and i the

microregion, ranging from 1 to 6. Each i represents a distinct

microregion within the oasis.

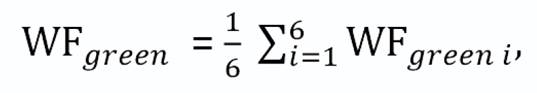

Once

the average values for the blue WF (m3 tonne-1) were

calculated at the oasis level (Equation 4), the water

availability for other uses (WAOU1policy site) in

the oasis was derived from Equation (6):

Where

WAOU1policy site represents the average annual

percentage of water availability for other uses that could be achieved at the

policy site, if the water distribution system were aligned with the water

requirements of grapevine crops; VWpolicy corresponds to the

average annual volume of water allocated to viticulture in the oasis (m3

year-1); and AW (agricultural water) is the average annual volume of

water allocated to agricultural use (m3 year-1).

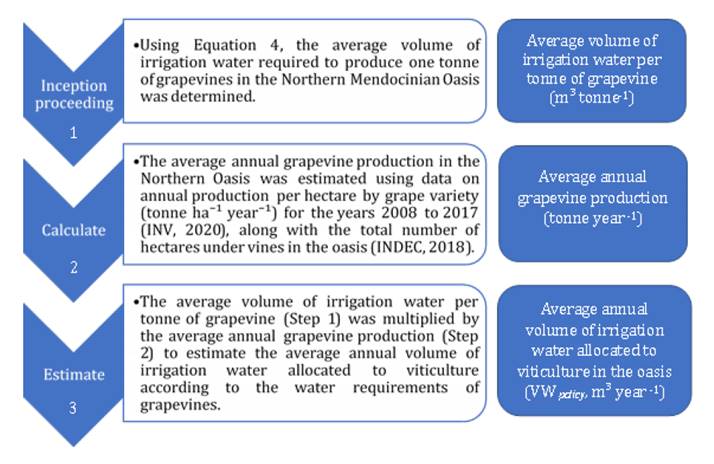

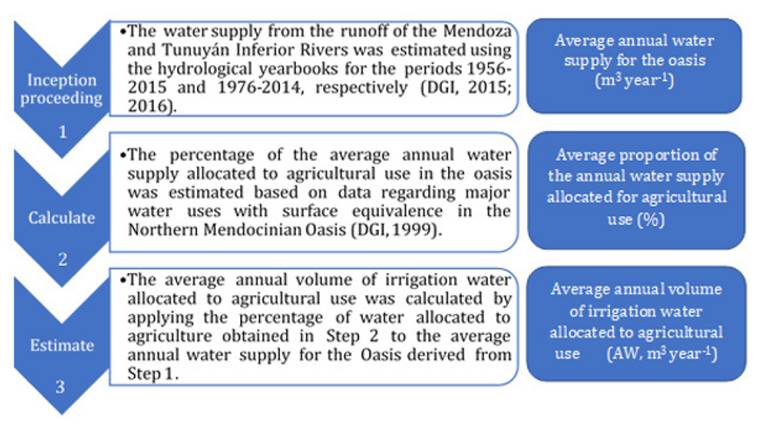

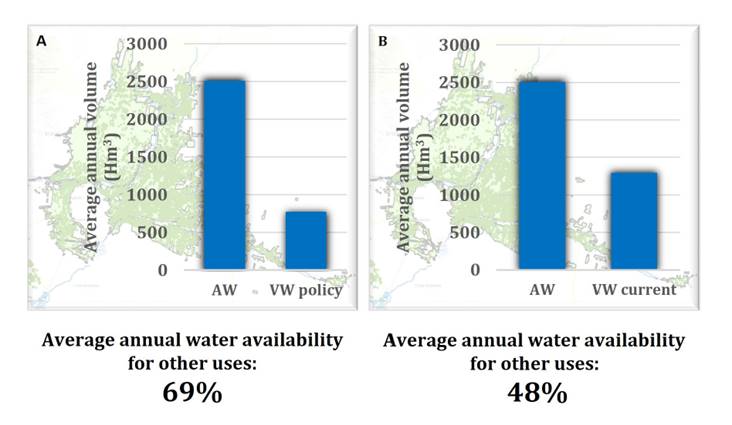

Figure 3 and figure 4, illustrate the

respective processes used to estimate the average annual irrigation water

volumes allocated to viticulture (VWpolicy, m3

year-1) and agriculture (AW, m³ year-1) in the oasis.

Source:

Own elaboration.

Fuente:

Elaboración propia.

Figure

3. Process for estimating the average annual volume of

irrigation water allocated to viticulture in the Mendocinian Northern Oasis.

Figura

3. Proceso para estimar el volumen

promedio anual de agua de riego asignado a la viticultura en el Oasis Norte de

Mendoza.

Source:

Own elaboration.

Fuente:

Elaboración propia.

Figure

4. Process for estimating the average annual volume of

irrigation water allocated for agricultural use in the Mendocinian Northern

Oasis.

Figura

4. Proceso para estimar el volumen

promedio anual de agua de riego asignado al uso agrícola en el Oasis Norte de

Mendoza.

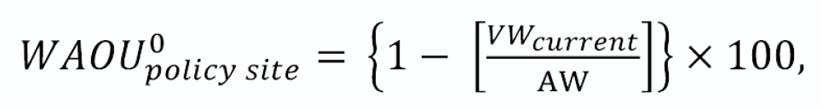

Next,

we calculated the current average annual water availability for other uses in

the policy site, formally:

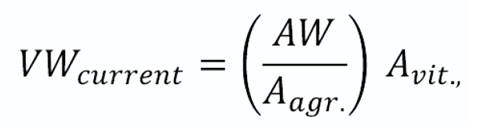

Where

WAOU0policy site represents the average annual

percentage of current water availability for other uses in the policy site; VWcurrent

(Equation 8) is the current average annual volume of

water allocated to viticulture (m3 year-1); and AW is the

average annual volume of water allocated to agricultural use (m3

year-1) in the oasis.

Where

VWcurrent represents the current average annual volume of

water allocated to viticulture in the policy site; AW is the average annual

volume of water allocated to agricultural use (m3 year-1);

Avit. (ha) is the area under vines in the oasis; and Aagr. (ha) is the total

cultivated area in the oasis (INDEC, 2018).

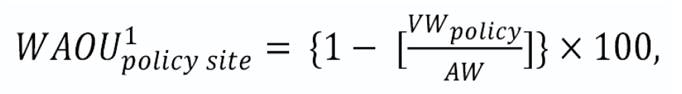

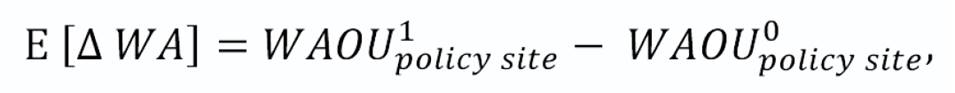

We

then calculated the percentage points that could be reallocated from vineyards

to other uses in the oasis. This was based on increased water availability and

its subsequent reallocation following the implementation of a water security

improvement policy (Equation 9).

Where

E [ ∆ W A] denotes the expected

change in average annual water availability resulting from the water security

improvement policy; WAOU1policy site is the

average annual percentage of water availability for other uses that could be

achieved in the policy site if the water distribution system were aligned with

the water requirements of grapevine crops; and WAOU0policy

sity is the average annual percentage of current water availability

for other uses in the policy site.

Finally,

we estimated the TEV of a water security improvement policy in the Mendocinian

Northern Oasis by applying Equation (10):

Where E [ ∆ W A] is the expected change in

average annual water availability resulting from water security improvement

policies; and WTPpolicy site is the value of a marginal

change in water security -achieved through a policy that conserves agricultural

water for reallocation to other uses- adjusted to the conditions of the policy

site.

Results and Discussion

The results follow five methodological stages to predict the TEV

of a water security improvement policy in the Mendocinian Northern Oasis (figure 2). The practical implications of these results are

discussed in the context of water security management, focusing on efficient

agricultural water allocation and conservation strategies.

Value

of a Marginal Change in Water Security Adjusted to the Conditions of the Policy

Site

According to Rosenberger and Loomis (2003) and Johnston

et al. (2021), the study site was selected for its similarity to the

policy site in four categories. These categories are: (i) socio-economic

characteristics, (ii) biophysical conditions, (iii) proposed environmental

changes, and (iv) economic valuation objectives.

A comprehensive

literature review was then conducted to identify potential study sites that met

these criteria. This process led to the selection of the study by Farreras and Abraham (2020). They estimated the welfare

effects of adapting viticultural management practices to climate change in the

Mendocinian Northern Oasis. The study applied the discrete choice experiment

(DCE) method, a valuation technique consistent with welfare economic theory (Bennett and Blamey, 2001). This method relies on

society’s stated maximum WTP to avoid or accept a marginal change in the

quantity or quality of an environmental good’s attribute. This is achieved

through the design of hypothetical markets presented via questionnaires.

Additionally, the use of the DCE at the study site allows for the identification

of marginal values for specific environmental attributes and has been shown to

perform better than other economic valuation methods when benefit transfers are

required (Hanley et al., 1998).

Surveys at the

study site were conducted in spring 2017. A representative sample of citizens

of the Northern Oasis of Mendoza was interviewed. The sample consisted of

randomly selected individuals aged between 24 and 80 years, all residing in

cities with populations of over 10,000 inhabitants. Approximately 90% of those

approached agreed to be interviewed. The interviews were conducted face-to-face

in the respondents’ homes, resulting in 678 valid observations.

Environmental

Attributes and Levels Used at the Study Site

The study valued

three attributes related to adapting vineyard practices to climate change in

Mendoza: (1) water availability for other uses, (2) use of chemical

fertilisers, and (3) use and conservation of biodiversity. Given the objective

of this study, the primary attribute of interest is the availability of water

for other uses.

The attribute had

four levels-41% (business-as-usual, BAU), 53%, 65%, and 76%. These represent

the average water available in 30 years for other uses: industry, public areas

(green spaces, urban trees), and irrigation of non-vineyard crops. These levels

ranged from the value expected under a BAU scenario to values above the BAU

level. The BAU level shows the situation projected in 30 years from now under

non-adaptive management practices in Mendocinian vineyards. Other levels show

potential outcomes from adapting viticultural practices to climate change.

Marginal

Benefit or Value to Be Transferred

The study by Farreras and Abraham (2020) estimated that a

representative citizen of the Mendocinian Northern Oasis was, on average,

willing to pay 13.05 (95% CI: 6.24-27.28) Argentine pesos [0.74 (95% CI:

0.35-1.55) US dollars] per household annually for an additional percentage

point in water availability for other uses, at 2017 prices subject to

adjustment for inflation, over the next 30 years. Figures in parentheses

indicate the limits of the 95% confidence interval.

Adjustment

Process

We adjusted the

estimated values at the study site to align with the conditions of the policy

site, following the methodology of Rolfe et al. (2015).

Their study demonstrated that transferring values between similar sites

requires straightforward adjustments. Since the study and policy sites

coincide, inflation was the adjustment factor used to align information and

ensure accurate value estimates for the policy site.

Adjustment

for Inflation

The estimated

values at the study site were adjusted using the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

This adjustment accounts for inflation between the interview period (September

2017) and November 2024 (Equation 1). The accumulated

inflation over this period was 6,393% (INDEC, 2024).

Therefore, a representative citizen of the Mendocinian Northern Oasis is

estimated to be, on average, willing to pay 847.34 (95% CI: 405.16-1,771.29)

Argentine pesos [0.83 (95% CI: 0.40-1.74) US dollars] per household annually

for an improvement in water security equivalent to an additional percentage

point in water availability for other uses, at 2024 prices over the next 30

years. Average exchange rate in November 2024: 1 US dollar equals 1,019.56

Argentinean pesos.

Average

Annual Water Availability for Other Uses Based on a Water Distribution System

Aligned with the Water Requirements of Grapevine Crops in the Policy Site

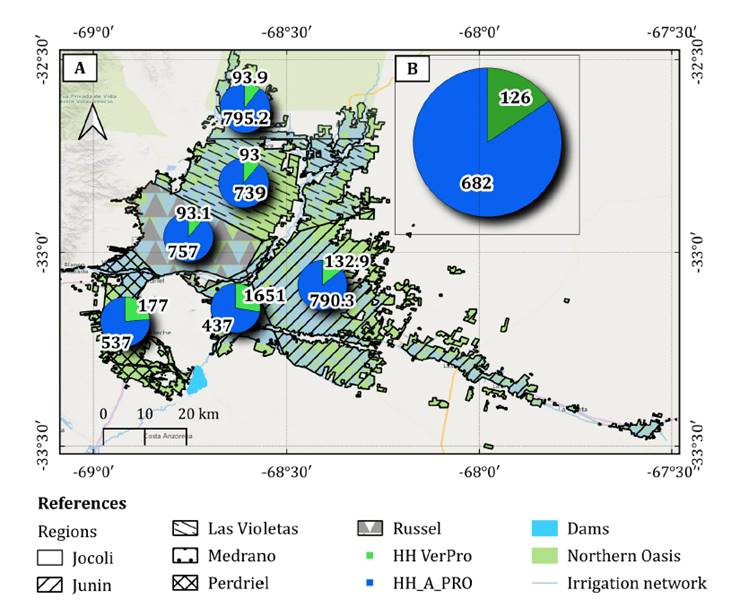

Using

meteorological, grapevine, and soil data, we estimated the blue and green WF of

vineyards at the microregional level by applying Equation (2),

and Equation (3), respectively. Figure 5A,

depicts the blue and green WF for each of the six microregions within the

Northern Oasis of Mendoza.

Source:

Own elaboration.

Fuente:

Elaboración propia.

Figure

5. Blue and green WF (m3 tonne-1)

(A) for each of the six microregions and (B) for the Mendocinian Northern

Oasis.

Figura

5. Huella hídrica azul y verde (m3

tonelada-1) (A) para cada una de las seis microrregiones y (B) para

el Oasis Norte de Mendoza.

Given that the crop

requires more water than is provided by rainfall, the deficit is compensated

through irrigation. As a result, the blue WF exceeded the green WF across all

microregions. The Jocolí microregion had the highest blue WF, at 795 m3

tonne-1,

while the Medrano microregion had the lowest, at 437 m3 tonne-1.

The variations in

WF across microregions result from a variety of factors, including local

climate conditions and agricultural management practices. This information may

be particularly useful for stakeholders involved in promoting efficient water

allocation and conservation strategies. For instance, a decision-maker may

prioritise water distribution based on specific crops’ water requirements. The

analysis of the WF enables the design of distribution schemes tailored to these

local needs. In this context, for the same crop and irrigation system,

microregions with higher WF need more water than those with lower footprints.

If resource distribution aligns with irrigation water demand, it becomes possible

to reduce water deliveries in certain microregions without compromising

agricultural productivity or associated ecosystems. This approach increases

water availability at the oasis scale, enabling more efficient resource

reallocation and strengthening long-term water security without sacrificing

productivity or ecosystem integrity (Grafton et al.,

2018).

Meanwhile, the

Mendocinian Northern Oasis averages 682 m³/tonne blue WF (Equation

4) and 126 m³/tonne green WF (Equation 5), as shown in figure 5B). This highlights the dominance of irrigation water

over effective rainfall in meeting the vineyard water requirements in this

region.

These results

partially align with previous findings in the literature. For example, Civit et al. (2018) estimated that the blue WF

for the most important varietals in the five wine-producing regions of Mendoza

ranges from 540.53 m³ tonne-¹

to 1,020.03 m³ tonne-¹.

On a global scale, Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2011)

reported an average blue WF of 608 m³ tonne-¹

in viticulture production for the period 1996-2005. Similarly, Herath et al. (2013) documented blue WFs of 601

m³ tonne-1 and 611 m³ tonne-¹ in vineyards in

the Gisborne and Marlborough regions of New Zealand, respectively. These

findings emphasise reliance on irrigation in viticulture. About 84% of vineyard

water needs were met through irrigation during the analysed period. This

underscores the need for sustainable water resource management.

We estimated that, under a water distribution system aligned

with the grapevine crops’ water requirements, 69% of water could, on average,

be available annually for other uses (Equation 6; figure 6A). This estimate is based on the average annual water

volumes allocated to viticulture (figure 3) and agriculture (figure 4).

Figure

6. Average annual percentage of water availability for

other uses in the Mendocinian Northern Oasis estimated under (A) the

implementation of a water security improvement policy and (B) the current water

management.

Figura

6. Porcentaje promedio anual de

disponibilidad hídrica para otros usos en el Oasis Norte de Mendoza estimado

bajo (A) la implementación de una política de mejora de la seguridad hídrica y

(B) la gestión hídrica actual.

Current

Average Water Availability for Other Uses in the Policy Site

We

estimated that, on average, 48% of water is currently available annually for

other uses in the Mendocinian Northern Oasis (Equation 7; figure 6B). This estimate is based on current average annual

water volumes allocated to viticulture (Equation 8)

and agriculture (figure 4).

Expected

Change in Average Annual Water Availability Due to a Water Security Improvement

Policy

Next, we estimated

the average percentage points of irrigation water that could be reallocated

from vineyards to other uses under a water security improvement policy (Equation 9). The average reallocation was estimated at 21

percentage points. This volume could be redistributed to industry, municipal

spaces (green areas, urban trees), and irrigation of non-viticultural crops.

Total

Economic Value of a Water Security Improvement Policy in the Policy Site

Assuming unitary

price elasticity, the TEV of reallocating an average of 21 percentage points of

water from vineyards to other uses can be estimated. This is calculated by

multiplying the 21-percentage-point change by the value of a

one-percentage-point increase in water availability for other uses.

Applying Equation (10), a water security policy that increases average

annual water availability for other uses by 21 percentage points corresponds to

an average household welfare gain of ARS 17,794.14 [USD 17.43] per year at 2024

prices (95% CI: ARS 8,508.36-37,197.09 [USD 8.40-36.54]) over the next 30

years.

Direct comparisons

are difficult due to differing units used to estimate WTP (e.g., per

hectare, time horizon). However, this finding aligns with Pellegrini

et al. (2023), who estimated social welfare changes associated with

improvements in specific water security components. Based on their literature

review, they reported households’ willingness to pay between 9.68 and 209.66 US

dollars per year for water purification services. For biodiversity habitat

conservation, willingness to pay ranged from 17.23 to 106.40 US dollars. For

cultural services such as aesthetic and recreational benefits, willingness to

pay ranged from 17.23 to 156.99 US dollars. WTP in the study of Pellegrini et al. (2023) are expressed in Euros.

We expressed them in US dollars using the average 2023 daily Euro - USD

exchange rate published, 1.08268509, by www.macrotrends.net

Our study adopts a

comprehensive approach to value a water security improvement policy, explicitly

addressing water reallocation to alternative uses. This analysis helps fill a

gap by providing a broader perspective that accounts for welfare associated

with overall water security enhancement.

Conclusions

Globally, many

regions face severe water scarcity, worsened by global changes increasing

uncertainty and variability in water availability. In this context, a paradigm

shift in water resource management is crucial. Aligning water allocation with

crop requirements improves management efficiency and strengthens long-term

water security, while protecting agricultural productivity and the integrity of

ecosystems. Understanding the benefits of such strategies is essential for

their successful implementation. This study addresses this gap by estimating

the changes in social welfare resulting from improved water security.

A distinctive

contribution of our study lies in the estimation of social welfare changes

resulting from water security improvements, expressed in monetary terms. This information

is particularly valuable for decision-makers, policymakers, and natural

resource managers. For example, with a fixed budget for a water security

improvement policy, decision-makers can evaluate whether the costs outweigh the

monetary benefits provided to citizens. Similarly, this estimation allows

policymakers to allocate resources efficiently and justify major water security

reforms to stakeholders and the public by emphasising socio-economic benefits.

Our

study found that the TEV of a water security improvement policy in the Northern

Mendocinian Oasis -resulting in a 21-percentage-point average increase in the

annual water availability for other uses- is equivalent to an average household

welfare gain of ARS 17,794.14 [USD 17.43] per year at 2024 prices (95% CI: ARS

8,508.36-37,197.09 [USD 8.40-36.54]) over the next 30 years.

These findings

offer decision-makers a robust basis for assessing the costs and benefits of

investments in water security, thereby enabling more informed public policy

decisions.

Following the

guidance of experts in BTM, the method was carefully applied to ensure a

state-of-the-art implementation. Recognising that transfer errors often arise

from differences between study and policy sites, we prioritised ensuring

similarity across four categories: (i) socio-economic characteristics, (ii)

biophysical conditions, (iii) proposed environmental changes, and (iv) economic

valuation objectives. This approach aimed to minimise transfer errors and

establish benefit transfer as a robust tool for obtaining the TEV of a water

security improvement policy.

Nevertheless, data

limitations led to restrictive assumptions. For instance, the estimation of

water reallocation from vineyards to other uses relied solely on surface water

data. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the policy’s TEV.

Similarly, the WF estimation of vineyards did not account for inefficiencies in

the irrigation system, potentially leading to an overestimation of the policy’s

TEV. Therefore, our results should be interpreted as approximations, within the

context of these limitations.

In

summary, this study demonstrates that social welfare is expected to increase

through the implementation of water security improvement policies. It provides

a framework for regions worldwide where irrigation water is a common resource

facing challenges like water scarcity, rising water demand, and climate change.

By assessing social welfare effects of an improvement in water security, it

offers critical insights for decision-makers, policymakers, and resource

managers in comparable global contexts. These insights support the design of

more informed water management strategies, ensuring long-term water security.

Acknowledgements

We

sincerely thank the two anonymous referees for their valuable contributions,

which have greatly improved the quality of this article. We also acknowledge

the support of the Secretaría de Investigación, Internacionales y Posgrado

(SIIP) at Universidad Nacional de Cuyo through project SIIP: 06/D006-T1.

Allen, R. G.,

Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. (1998). Crop evapotranspiration:

Guidelines for computing crop water requirements (FAO Irrigation and

Drainage Paper N° 56). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Bennett, J. &

Blamey, R. (2001). The choice modelling approach to environmental valuation (p.

269). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Boutwell, J. L.

& Westra, J. V. (2013). Benefit transfer: A review of methodologies and

challenges. Resources, 2(4), 517-527.

https://doi.org/10.3390/resources2040517

Carson, R. T.,

Carson, N., Alberini, A., Flores, N. & Wright, J. (1993). A bibliography

of contingent valuation studies and papers. Natural Resources Damage

Assessment.

Castex, V., Morán,

E. & Beniston, M. (2015). Water availability, use and governance in the

wine producing region of Mendoza, Argentina. Environmental Science &

Policy, 48, 1-8. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.12.008

Civit, B.,

Piastrellini, R., Curadelli, S. & Arena, A. P. (2018). The water consumed

in the production of grapes for vinification (Vitis vinifera): Mapping

the blue and green water footprint. Ecological Indicators, 85, 236-243.

Dirección de

Agricultura y Contingencias Climáticas. (2021). Informe técnico [Dataset].

Departamento

General de Irrigación. (1999). Plan hídrico para la provincia de Mendoza.

Bases y propuestas para el consenso de una política de estado. Gobierno de

Mendoza.

Departamento

General de Irrigación. (2015). Balance hídrico río Tunuyán Inferior (Cap.

5, p. 129).

Departamento

General de Irrigación. (2016a). Balance hídrico río Mendoza (Cap. 4, p.

128).

Departamento

General de Irrigación. (2016b). Aquabook. http://aquabook.agua.gob.ar/

Duek, A. E. (2018).

Escenarios de uso sostenible del recurso hídrico en el sector agrícola de

Mendoza. 4° Encuentro de Investigadores en Formación en Recursos Hídricos,

11. https://www.ina. gov.ar/ifrh-2018/pdf/IFRH_2018_paper_4.pdf

Farreras, V.,

Riera, P., & Salvador, P. F. (2017). Environmental valuation with

periodical payments in high-inflation economies: An Argentinean case study. Ecological

Economics, 138, 56-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.03.028

Farreras, V., &

Abraham, L. (2020). Valuation of viticultural adaptation to climate change in

vineyards: A discrete choice experiment to prioritize trade-offs perceived by

citizens. Wine Economics and Policy, 9(2), 99-112.

Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2024). CROPWAT 8.0 for

Windows [Computer software]. https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/cropwat/en/

Grafton, R. Q.,

Williams, J., Perry, C. J., Molle, F., Ringler, C., Steduto, P., Udall, B.,

Wheeler, S. A., Wang, Y., Garrick, D., & Allen, R. G. (2018). The paradox

of irrigation efficiency. Science, 351, 748-750.

Hanley,

N., Wright, R. E., & Adamowicz, V. (1998). Using choice experiments to

value the environment. Environmental and Resource Economics, 11:

413-428. https://doi. org/10.1023/A:1008287310583

Herath, I., Green,

S., Singh, R., Horne, D., van der Zijpp, S., & Clothier, B. (2013). Water

footprinting of agricultural products: A hydrological assessment for the water

footprint of New Zealand’s wines. Journal of Cleaner Production, 41, 232-243.

Hoekstra, A. Y.,

Chapagain, A. K., Aldaya, M. M., & Mekonnen, M. M. (2011). The water

footprint assessment manual: Setting the global standard. Routledge.

https://waterfootprint.org/

resources/TheWaterFootprintAssessmentManual_English.pdf

Instituto Nacional

de Estadísticas y Censo. (2018). Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2018. Cuadros

estadísticos. https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-3-8-87

Instituto Nacional

de Estadísticas y Censo. (2024). [Dataset].

https://www.indec.gob.ar/ftp/cuadros/ economia/sh_ipc_12_24.xls

Instituto Nacional

de Tecnología Agropecuaria. (1990). Atlas de Suelos de la República

Argentina.

Instituto Nacional

de Vitivinicultura. (2020). Relevamiento Vitivinícola Argentino-Sector

Primario. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/inv/vinos/estadisticas/regiones-vitivinicolas

Johnston, R. J.,

Boyle, K. J., Loureiro, M. L., Navrud, S., & Rolfe, J. (2021). Guidance to

enhance the validity and credibility of environmental benefit transfers. Environmental

and Resource Economics, 79, 575-624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00574-w

Katz, D. (2016).

Undermining demand management with supply management: Moral hazard in Israeli

water policies. Water, 8(4), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8040159

Konapala, G.,

Mishra, A. K., Wada, Y., & Mann, M. E. (2020). Climate change will affect

global water availability through compounding changes in seasonal precipitation

and evaporation. Nature Communications, 11, 3044.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16757-w

Lauro, C., Vich, A.

I. J., Otta, S., Moreiras, S. M., Vaccarino, E., & Bastidas, L. (2021).

Recursos hídricos superficiales de la vertiente oriental de los Andes Centrales

(28°-37°S) en contexto de variabilidad hidroclimática. Boletín de Estudios

Geográficos, 116, 45-71.

Lauro, C., Vich, A.

I. J., Rivera, A., Otta, S., Moreiras, S. M., Bastidas, L., & Vaccarino, E.

(2022). Patrones de variabilidad hidroclimática en los Andes Centrales

(30-37°S) de Argentina. Geoacta, 44(1), 1-22.

Mekonnen, M., &

Hoekstra, A. Y. (2011). The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and

derived crop products. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 15(5),

1577-1600. https://doi. org/10.5194/hess-15-1577-2011

Monnet, M.,

Vignola, R., & Aliotta, Y. (2022). Smallholders’ water management decisions

in the face of water scarcity from a socio-cognitive perspective: Case study of

viticulture in Mendoza. Agronomy, 12(11), 2868.

https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12112868

Morábito, J.,

Mirábile, C., Salatino, S., Pizzuolo, P., Chambouleyron, J., & Fasciolo, G.

(2005). Eficiencia de riego actual y potencial en el área regadía del río

Mendoza. https://repositorio.ina.gob.ar/

items/cd398433-7fa6-4b9c-adb9-0b7ebc2dcb97

Morábito, J.,

Mirábile, C., & Salatino, S. (2007). Eficiencia del riego superficial,

actual y potencial, en el área de regadío del río Mendoza (Argentina). Ingeniería

del Agua, 14, 199-214. https:// doi.org/10.4995/ia.2007.2912

Pellegrini, E.,

Dalmazzone, S., Fasolino, N. G., Frontuto, V., Gizzi, P., Luppi, F., Moroni,

F., Raggi, M., Zanni, G., & Viaggi, D. (2023). Economic analysis under the

Water Framework Directive: The state of the art and way forward. Water, 15(23),

4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15234128

Pérez Blanco, C.

D., Hrast Essenfelder, A., & Perry, C. (2020). Irrigation technology and

water conservation: A review of the theory and evidence. Review of

Environmental Economics and Policy, 14(2).

Rivera, J. A.,

Naranjo Tamayo, E., & Viale, M. (2020). Water resources change in

Central-Western Argentina under the Paris Agreement warming targets. Frontiers

in Climate, 2, 587126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2020.587126

Rivera, J., Lauro,

C., & Otta, S. (2021). Cuantificación del déficit hidrológico reciente en

la región de Cuyo a partir de indicadores de caudales bajos. Boletín de

Estudios Geográficos, 116, 23-44.

Rodríguez, J., De

la Iglesia, F., & Ocvirk, M. (2000). Fenología de cultivares de vid (Vitis

vinífera L.) en Luján de Cuyo. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias, 32(2), 15-24. http://bdigital. uncu.edu.ar/11001

Rolfe, J., Windle,

J., & Johnston, R. J. (2015). Applying benefit transfer with limited data:

Unit value transfers in practice. In R. J. Johnston, J. Rolfe, R. S.

Rosenberger, & R. Brouwer (Eds.), Benefit transfer of environmental and

resource values: A guide for researchers and practitioners (p. 381-398).

Springer.

Rosenberger, R.,

& Loomis, J. (2003). Benefit transfer. In P. Champ, K. Boyle, & T.

Brown (Eds.), A primer on nonmarket valuation (p. 445-482). Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Servicio

Meteorológico Nacional. (2024). Estadísticas climatológicas normales período

1991–2020. https://www.smn.gob.ar/descarga-de-datos

United States

Department of Agriculture. (2024). Soil water characteristics (Version

6.02.72) [Computer software]. https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/software/

download/?softwareid=492&modecode=80-42-05-10

Villodas, R.,

Andino, M., Baduí, M. T., & Marinelli, S. (2023). Distribución de riego en

función de la demanda-cuenta de agua. XXVII Congreso Nacional del Agua,

Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Zetland,

D. (2021). The role of prices in managing water scarcity. Water Security, 12,

100081. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.wasec.2020.100081